The international attention that Jamie Reid’s death has garnered has been astonishing, from the LA Times to the Hong Kong Daily News, television, radio, and the enormous electronic screen at London’s Victoria station beaming down the news to scurrying commuters. Somehow this level of attention for a dead artist seems way greater that anything we are used to in the hermetic art world. Why has it happened? Because Jamie Reid’s work, from his breakout artwork for Malcolm McLaren and the Sex Pistols in the late 1970s to the timeless, spiritually and druidically inspired land art of his final years, had a profound affect on British popular culture way beyond that of almost any artist I can think of. And Reid was most certainly an artist, a classically trained one, with a daily practice. It is just that his most effective medium was the ether, and that is a place where the ineffable exists.

I first met Reid when I was tasked with organising a big retrospective of his work in New York in 1997 called Peace Is Tough. He arrived with a phalanx of Scousers and settled in to the Gramercy Park Hotel, hanging a God Save The Queen flag—his shock-inducing, epochal 1977 cover artwork for the Pistols—out of his hotel window.

He was guarded but generous with his time. We circled each other but came from similar London backgrounds, he from Croydon, and I from Bromley. That show travelled to Athens, Tokyo and then to Dublin, which became another gathering place for his tribe. We had lasers of his drawings shooting across the Liffey and music from Iarla Ó Lionáird of Afro Celt Sound System. We had a terrific time. A large Union Flag with its centre burned out was snatched from the gallery by heavies and thrown into the river to float away. We never found out if we had offended the loyalists or the unionists. But it was a victory for Reid, regardless. He had reached out and touched a nerve.

Reid was always fascinating. Ask him about Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen and the Sex Pistols and he would tell you about Henry Purcell. Ask him about his childhood and he would tell you about Fulham FC.

Later in the 1990s I started working with Nan Goldin on the Bowery neighbourhood of New York, and my time for Reid had to be curtailed, though we stayed in touch. When I returned to the UK in 2006 one of the first things I did was set off for Knighton in the Welsh borders with Reid and his wife Maria Hughes, where we talked and walked.

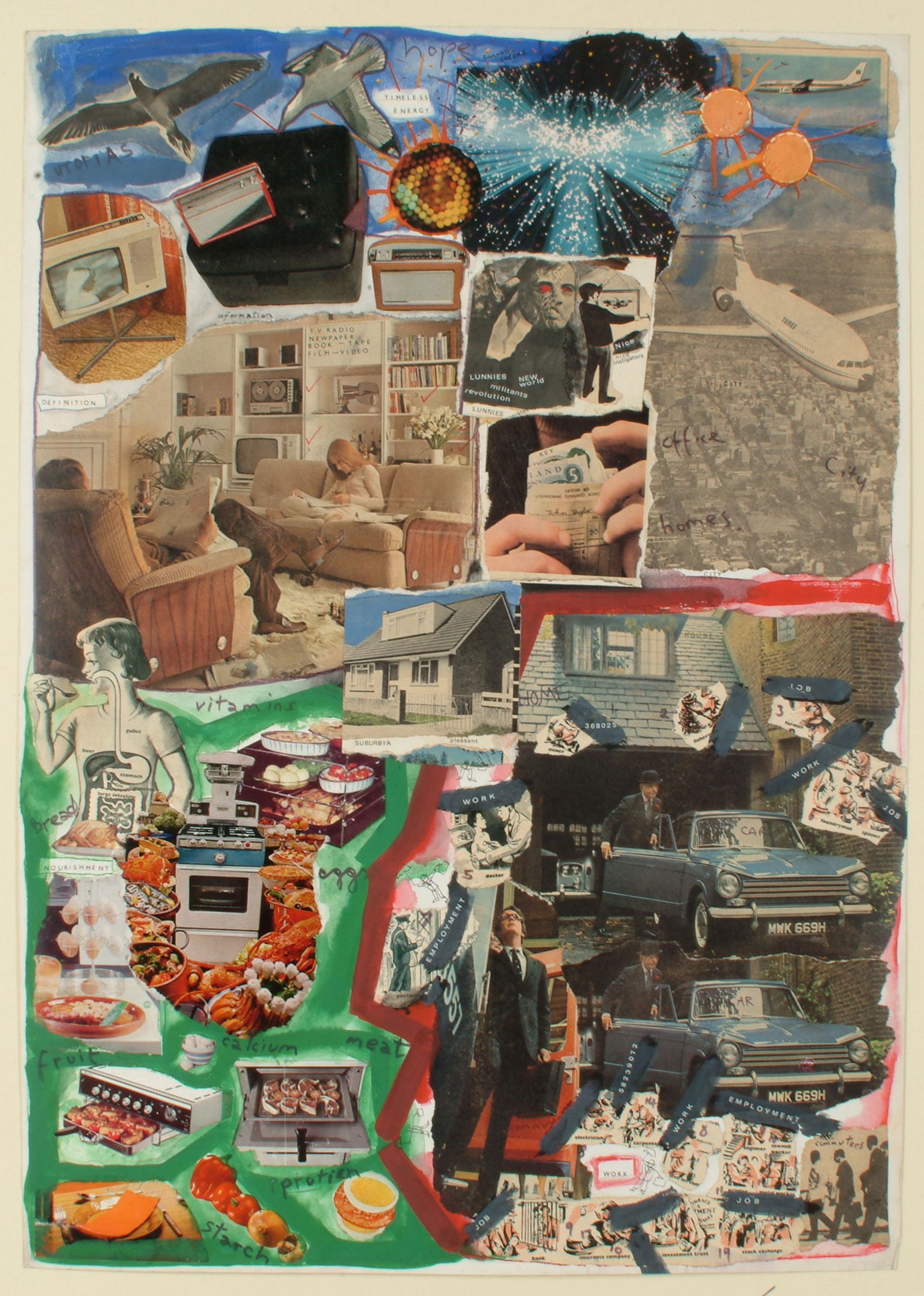

Jamie Reid, Work and Play, 1972 Courtesy Tate Collection

Thereafter we were close working partners. Reid was always fascinating. Ask him about Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen and the Sex Pistols and he would tell you about Henry Purcell. Ask him about his childhood and he would tell you about Fulham FC. Always evasive but never dull. Occasionally little snippets of his heralded past would slip out. Once we were in a cab crossing Manhattan and I pointed out that we would soon pass the Chelsea Hotel where Sid and Nancy’s terrible drama came to its climax. Reid became visibly agitated and insisted that we make a significant detour. His heart had been cleaved by Sid’s death in 1979 and had not healed. Many years later he was lying in a hotel room late at night, listening to the radio when an hour-long programme by his dear friend Malcolm McLaren came on, Jamie turning the light off and lying there in the dark, enjoying the magic.

Although from Croydon, Reid lived for nearly 40 years in Liverpool, where he was embraced principally because of his love for the Scouse queen actress Margi Clarke. They had formed a gloriously quixotic partnership in the ruins of the Pistols, running away to Paris to live in penury. Together they wrote songs and worked on a project called Leaving the 20th Century, a phrase Reid had settled in print a decade before when he’d been asked to design the layout of Christopher Gray’s 1974 translation of the writings of the Situationist International (SI). It is often whispered that punk had its roots in the SI but it is an incontrovertible truth that it did. Reid referred to Situationist tenets often in his later years, not least decrying the Society of the Spectacle and the domination of Capital over Community in our cities and towns, but also the infertile “green factories” of our agricultural industries.

Towards the late 1980s, Reid was thrown a lifeline by the designer and founder of design company Assorted iMaGes, Malcolm Garrett, which brought him in to Shoreditch, east London, with the offer of a studio space and a colour photocopier. Both were used to an industrial level, with Jamie revelling in the mire of it all. Here he became friends with a new gang of London wonders—Michael Clark, Judy Blame and Dave Baby, Frick and Frack, and Boy George.

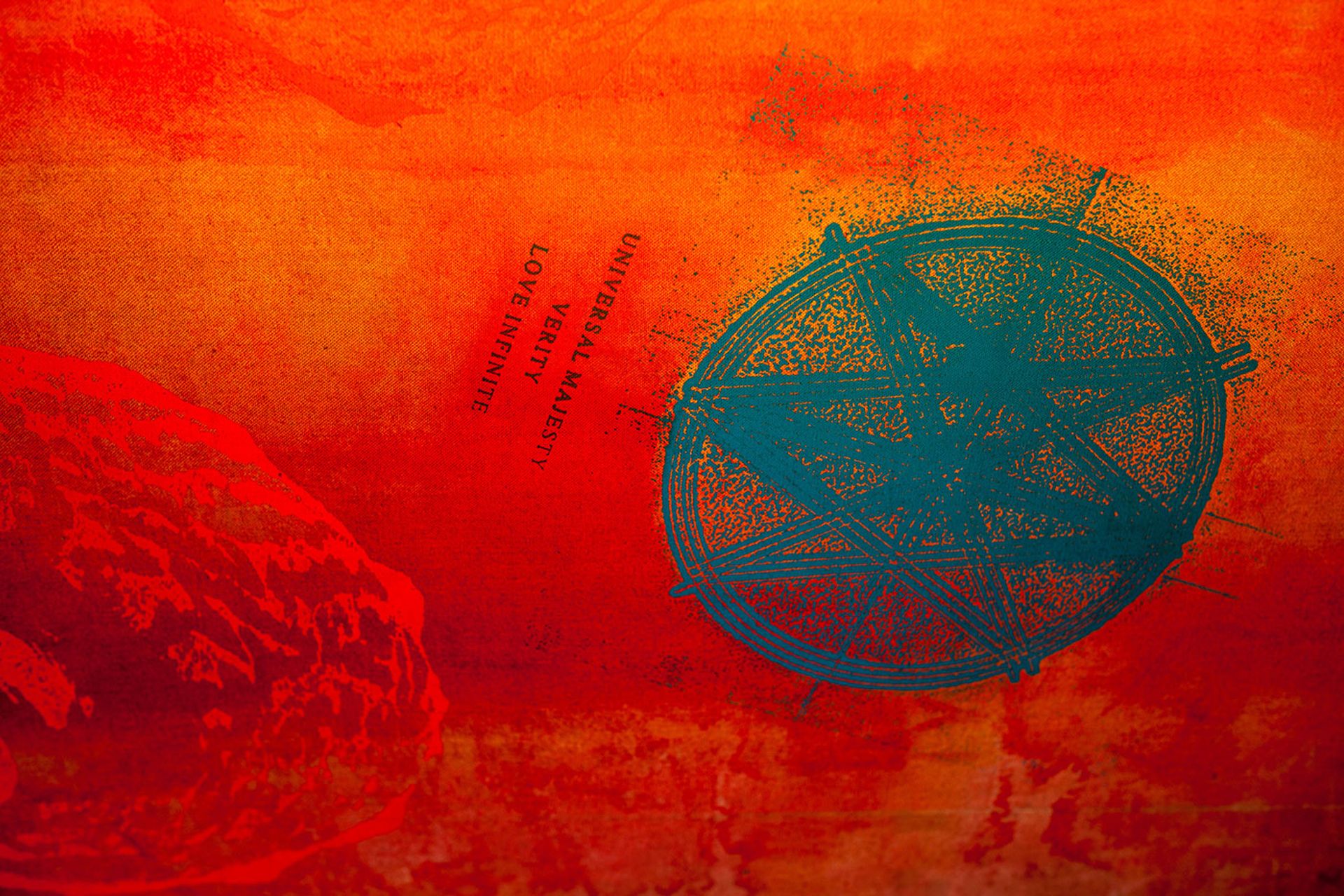

Everyone loved Reid, and as an artist who revelled in collaboration and chance, he would offer his generosity to all who knocked on his studio door. In time, that building on Curtain Road was taken over room by room by the Strongroom recording studios and thereafter by Reid, who decorated the various rooms through a ten-year period in a tumult of colour and magical symbols, not least the OVA which became his glyph—essentially an encircled A for Anarchy with a V for Victory. The Curtain Road work remains, though sadly not easily accessible to the public. It was here that he met the also recently departed musician Simon Emmerson, becoming a fully paid up member of his beloved Afro Celt Sound System.

Jamie Reid, detail of artwork at Strongroom studios, Curtain Road, London, featuring Reid's OVA glyph—an encircled A for Anarchy with a V for Victory Photo by Patrick Dunn. Courtesy Jamie Reid Estate

Jamie’s great uncle George Watson MacGregor Reid (c1860-1946) cast a long shadow over the family. He had likely been involved with Glasgow anarchists but also with a nascent Golden Dawn because of his fascination with Eastern esoterica, being gifted the MacGregor name as an inner initiate. Aleister Crowley briefly became a friend and then a foe, as George Reid’s interests were much more benign. He became MP for Clapham South, hosting striking miners, holding mass rallies on Clapham Common, and in his parallel life as Chosen Chief of the Druid Order, hosted fence-jumping protests for access to Stonehenge for solstice rituals, often getting into enthusiastic conflict with the law for his troubles.

Jamie Reid, Sunrise over Stones, 1990. Reid's great uncle had been Chosen Chief of the Druid Order Courtesy Jamie Reid Estate

This twin-hemisphere world of societal and spiritual improvement was something the young Jamie grew up with. His father Jack Reid had been the City Editor of the Daily Sketch but never invested a penny in his life. He rather invested his younger son—Jamie’s brother Bruce was five years older—with a love of both the Romantics and Thomas Paine, the man who inspired not one but two national revolutions, in the United States and then France, dying penniless. The Reids had originally come from Montrose, and claimed Rob Roy as a direct ancestor which, as with many Reid family legends, may have more than a grain of improbable truth in them. Uncle George was clearly a terrific teller of tales and inventor of extraordinary situations. I strongly suspect that when Jamie Reid first met Malcolm McLaren at Croydon College—trying to engineer some electrical device with zero technical ability and most likely endangering not just his own life but of the rest of the faculty—he felt a rush of familiar, rebellious comradeship.

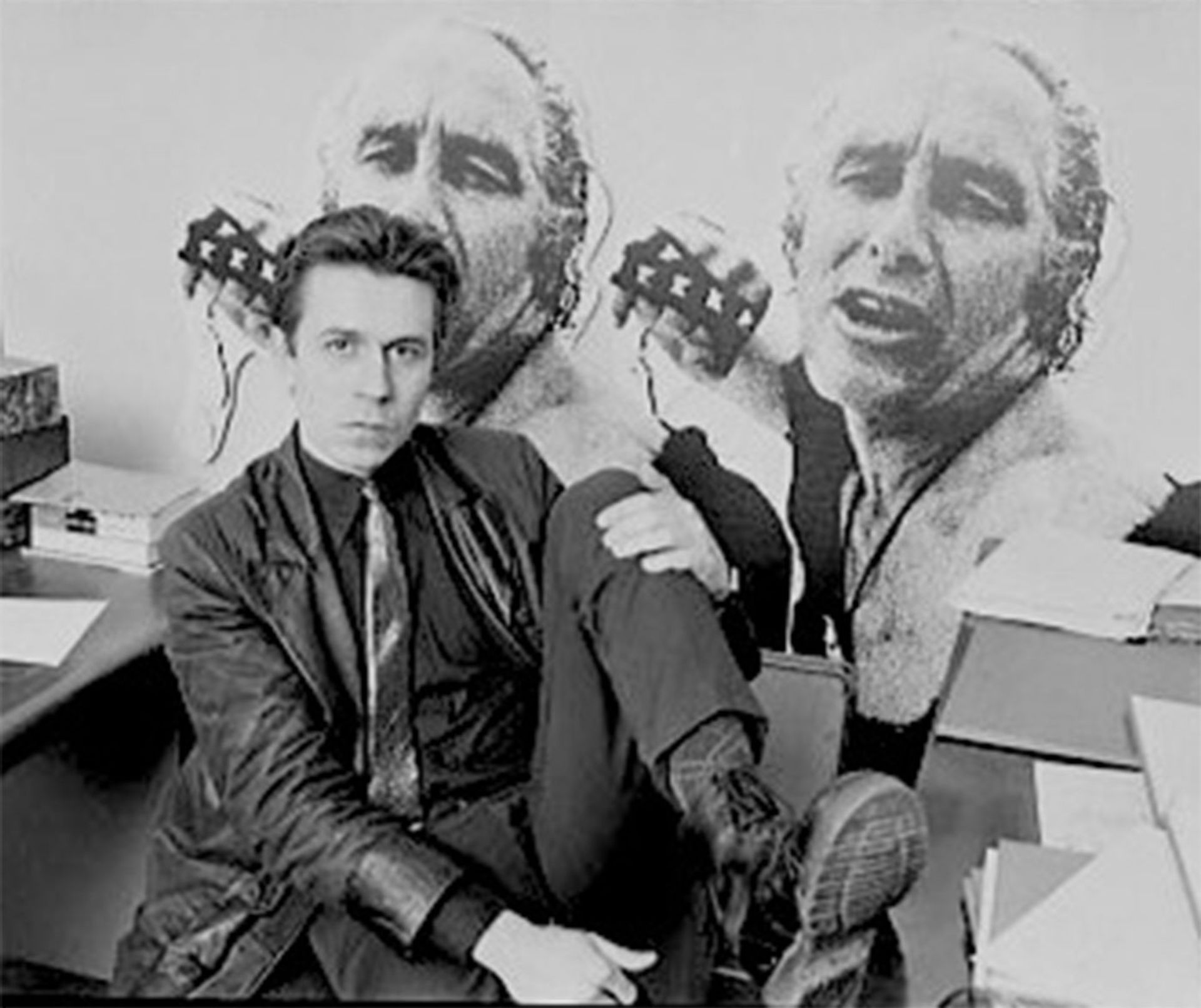

Reid at Glitterbest, the Sex Pistols' management company, 1978 Photograph Barry Plummer

In recent years, Reid took to praising McLaren for his genius, whenever the chance arose. He was forever supporting the underdog (he was probably the only person outside of Nancy Spungen’s own family to say that he liked and admired her for her intellect and willingness to throw her family fortune to the wind), not least Charlie Mingus, whose 1971 book Beneath the Underdog was a constant reference, as was Mingus’s music. Reid had seen Mingus walk off stage early at a Ronnie Scott’s gig, in London, followed him out into Leicester Square and watched him scowl his way through plate after plate of chips. Jazz really was Reid’s pleasure, not punk rock. In his regular calls (sometime up to three times a day) he would tell me about his loathing of power structures, be they church or state. He was unexpectedly and equally disdainful of both Boris Johnson and Keir Starmer, having seen them exit parliament as two Oxford chums, sharing a joke.

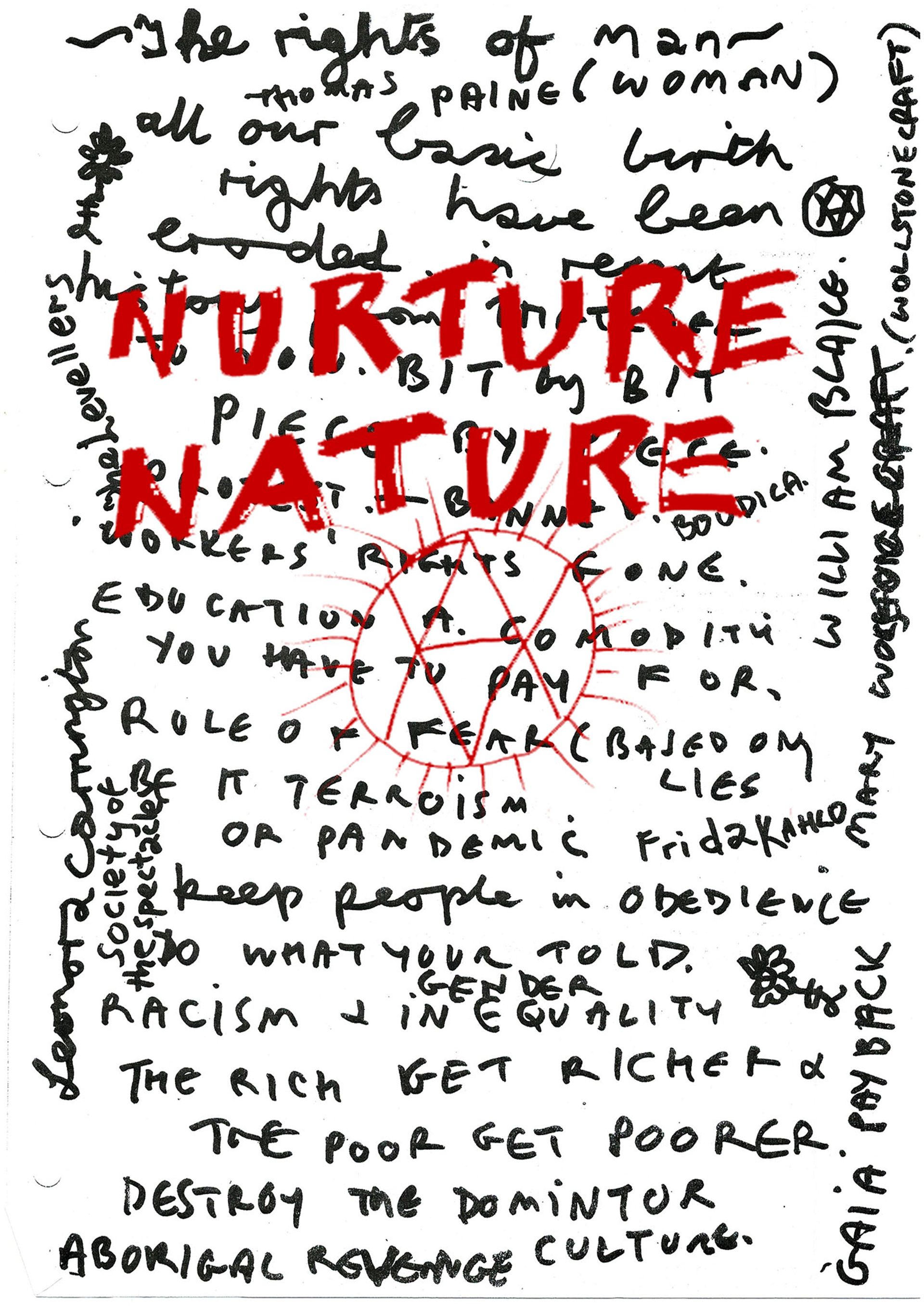

Jamie Reid, Nurture Nature (2023) Courtesy Jamie Reid Estate

After decades in Liverpool (marrying Maria Hughes in 1996), Reid found a wonderful community at the Florence Institute in Toxteth. A friend had introduced him to the decrepit ex-boys club and drew him in to the campaign to rebuild and reopen the building as a community centre. In 2016 at a meeting to discuss a possible exhibition of Reid’s print work, he and I discussed quietly the possibility of using the space to show a complete retrospective, which we did, hanging early drawings and paintings, mid-1970s work from his time as co-founder of the campaigning magazine Suburban Press, key pieces from the Pistols period, through protest work from the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, hangings used for druidic rituals, the rather delightful Fuck Forever bed. Also a selection of rough canvas paintings made during the previous decade, and the 7.8m-long Sex Pistols Mural, made from the walls of the Brixton Art Gallery—torn down after a show there in 1984, framed and subsequently travelling with the 1989 exhibition On the Passage of a Few People Through a Rather Brief Moment in Time: The Situationist International 1957-1972, organised by Peter Wollen and Mark Francis for the Centre Pompidou in Paris before going to the ICA London and ICA Boston.

Such actions in off-grid spaces were normal for Reid as he was wary of the art world and they wary of him. Although his work is rightly in leading institutions worldwide, they have rarely offered him exhibitions. Perhaps that will change now. We will see. I look after his archive, and though we often lend items out for exhibition (a body of political work that travels under the title Taking Liberties is now in exhibition at De Montfort University in Leicester, travelling on to Northampton University later this year) I cannot help but wish he had received more institutional attention in his lifetime.

Land art in Cornwall

His final major work is nowhere near a gallery, however, but in a field in Cornwall. Two years ago he was offered the free use of a wildflower meadow at Heligan in Cornwall. We agreed that we would sow a huge OVA in the field with the help of our friend Richard Scott from the National Wildflower Centre. Of course laying out a geometric shape tilted to due north at 100m diameter on a slightly domed and tilting field is no mean feat, but it was achieved, and last year Reid’s OVA emerged in the Cornish sunlight. We aligned the project with the druidic concept of the Eight Fold Year, celebrating the equinoxes, solstices and quarter-day festivals at the field. The final event was for the Spring Equinox, featuring a procession, smoke and some very beautiful music. Wildflower seeds from the field have been cast in many places, including at the site of Long Kesh prison in Northern Ireland, a place much in need of beauty.

Jamie Reid, OVA, 2022, Heligan, Cornwall Courtesy Heligan Gardens

Although Jamie Reid’s health meant he couldn’t make it to Heligan (with me a very poor substitute) we were able to recently beam him in via Zoom to the Nuart Festival in Aberdeen, which he enjoyed tremendously. Thankfully, things have ended on a high—a substantial book is nearly drafted, a film is underway and a 12-inch single, “Calling Back The Ancestors”, is about to emerge with accompanying video. Reid was absolutely adamant that we proceed with making this project come good, even though he could not take part, so maybe there was some prescience there.

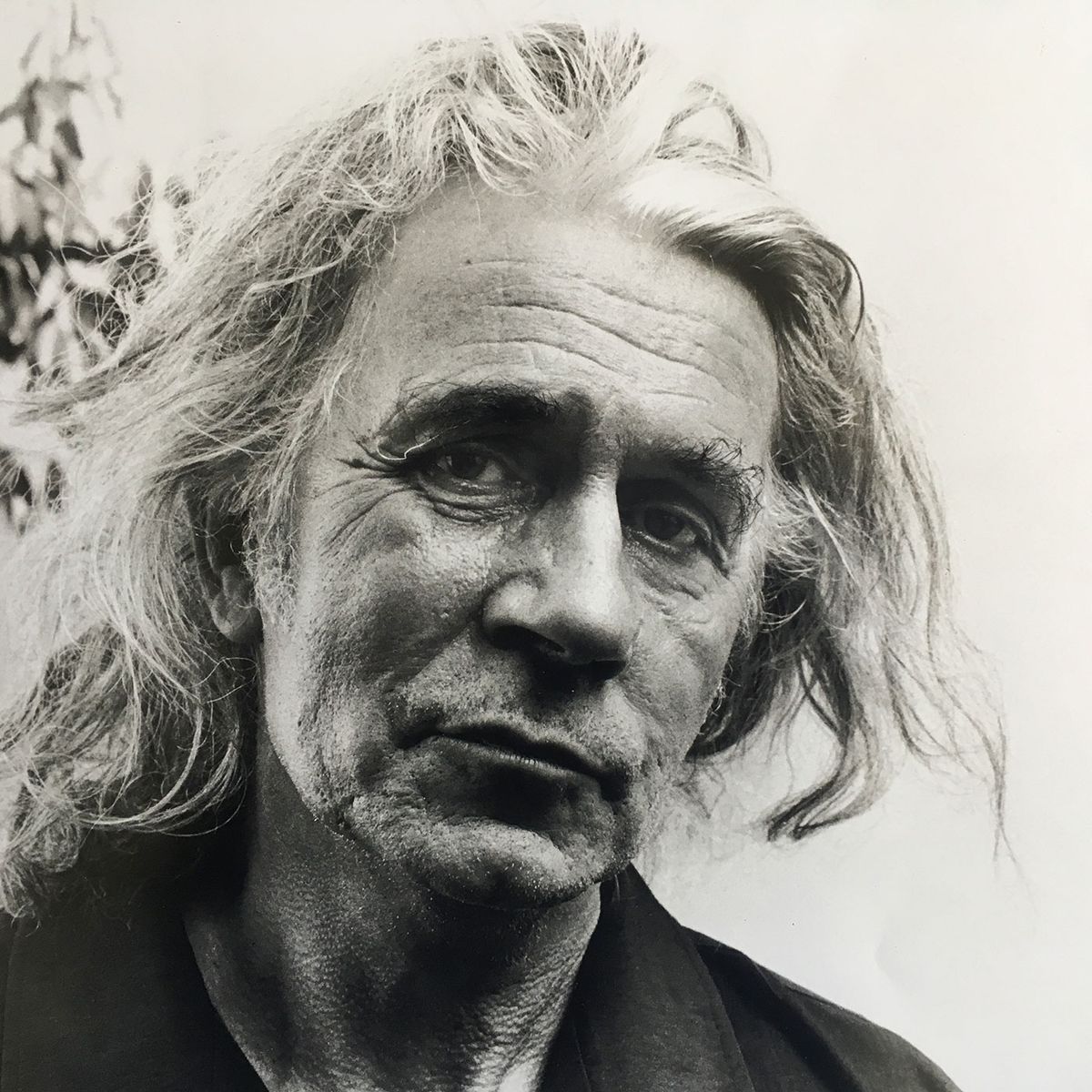

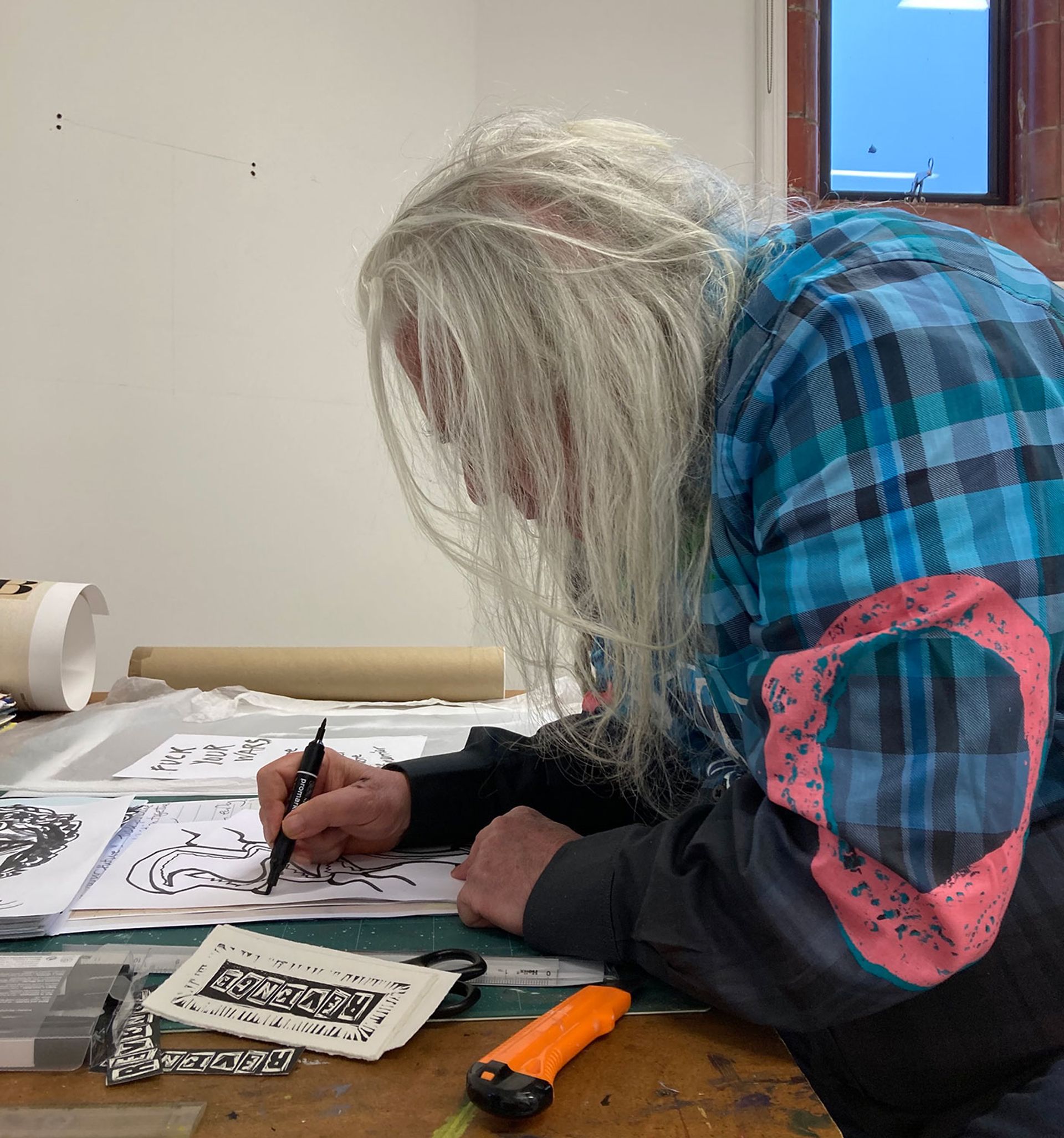

Reid in his Liverpool studio wearing one of the shirts he made with the New York clothing company JCRT (2023) Photograph by John Marchant

He was a dear friend, who taught me more than I could ever understand. Though I will continue to work with his archive and happily show his work to interested curators and visitors, I will miss his obsessions and digressions, his generosity and love.

Jamie Reid is survived by his daughter Rowan, grand-daughter Rose and at least two generations of Romantic schemers worldwide.

Jamie MacGregor Reid; born Croydon, south London, 16 January 1947; partner of Margi Clarke (one daughter); married 1996 Maria Hughes; died Liverpool 8 August 2023.

- John Marchant is a Brighton-based gallerist and curator, who holds the Jamie Reid Archive and was close to Reid from the 1990s. Marchant has also had long-standing working relationships with Nan Goldin and Gary Hume.