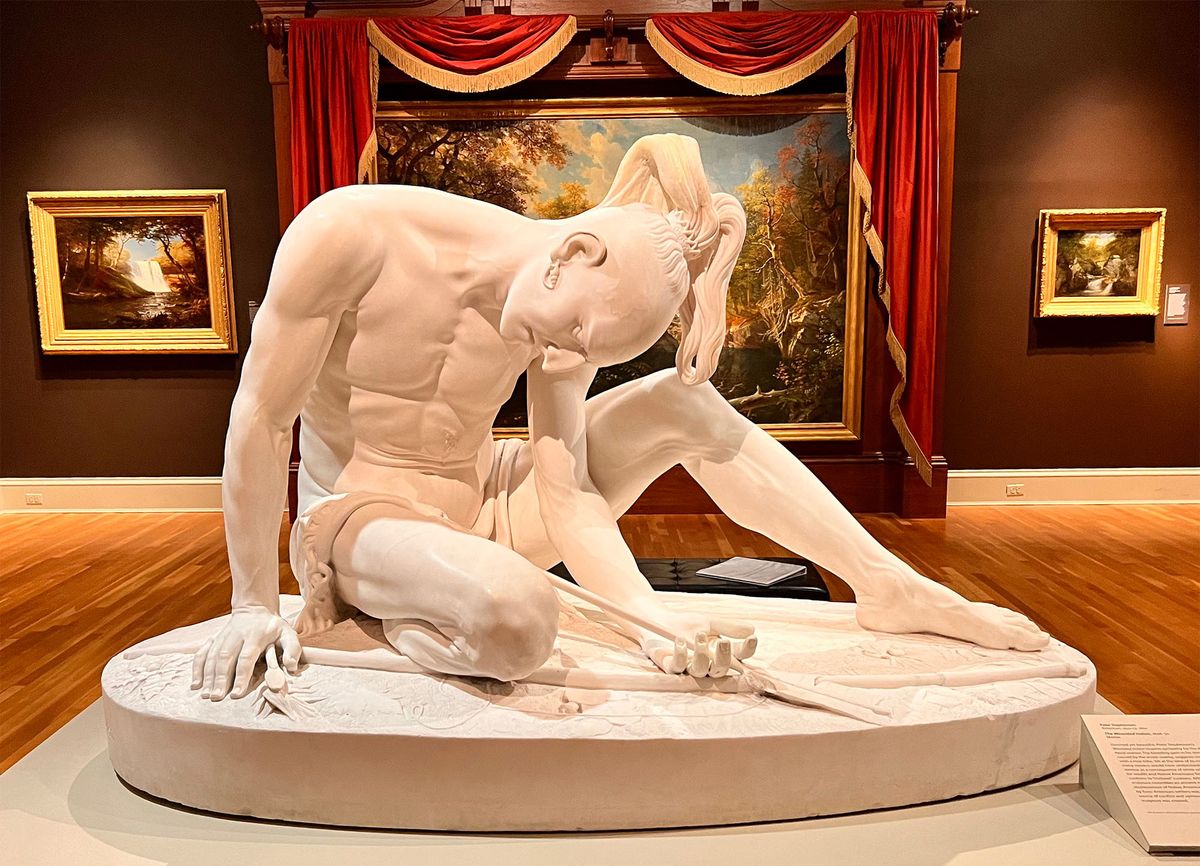

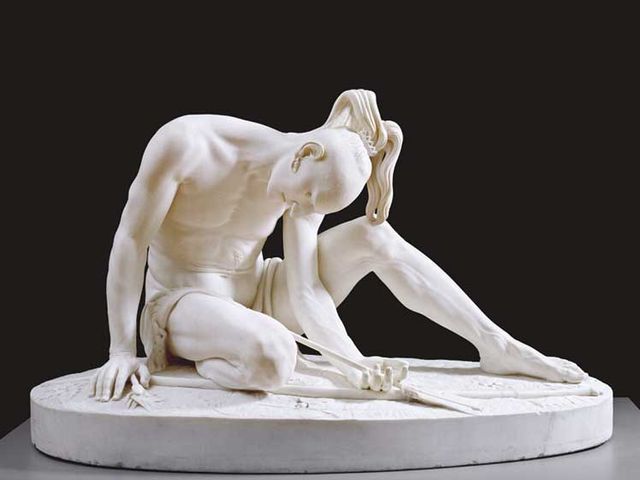

The Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk Virginia has agreed to return Peter Stephenson’s marble sculpture The Wounded Indian (1850) to the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association (MCMA), a philanthropy in Boston founded by the silversmith Paul Revere in 1795.

The figure, which Stephenson modelled on the Roman sculpture The Dying Gaul, had been held by the MCMA since 1893 and disappeared, presumed destroyed, when the organisation vacated its building in 1958. It was acquired by the collector Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. from the dealer James Ricau in 1986. The Chrysler Museum has no record of a legal sale where Ricau obtained it.

The graceful figure of an injured Indigenous man is said to be the first life-sized sculpture made entirely of marble quarried in the United States. The MCMA, which lacks its own galleries, plans to exhibit it in the Boston area.

The Chrysler Museum and the MCMA have been arguing over its return for more than 20 years. The MCMA learned in 1999 that it was on view at the museum in Norfolk, Virginia. At times the museum argued that the figure once held by the MCMA must have been a copy.

The Wounded Indian was made by the British-born Stephenson at a time when most Native American people in the US had been killed by settlers, wiped out by disease or forcibly dispossessed of their land and pushed west of the Mississippi River. Stephenson died young in an asylum, and the work passed among institutions until the MCMA agreed to take it in 1893. When the MCMA vacated its building in 1958, it was assumed to have been damaged.

The parties had been close to deal for a temporary loan to the MCMA for exhibition in Boston. That proposed arrangement would also have included a recognition of the MCMA’s earlier ownership and a $200,000 payment by the Chrysler to the MCMA for its costs in recovering the work.

MCMA lawyers say the Chrysler reneged on that settlement over the $200,000 and asked the FBI to investigate. The Chrysler insisted that no deal was ever in place. The current agreement involves no payment by the Chrysler, whose director, Erik H. Neil, says the museum was “pleased with the amicable solution”. MCMA lawyers say there is no plan to sell the work.

“When the story became public, it really helped the Chrysler understand where the MCMA was coming from,” says Paul Revere III, a descendant of the organisation’s founder.

The dispute over The Wounded Indian is a twist on battles over provenance. The statue is not a Nazi-looted work, an object of colonial plunder or an illegally excavated ancient sculpture, but a work that passed from a US institution into the American art trade without any evidence (until Walter Chrysler got it) of a legal sale or acquisition.

And the MCMA, without a gallery, finds itself in a similar position to that of claimant countries that demand the return of heritage but lack museums to exhibit them. The MCMA, which sponsors technical training, cited a promise made in the 1890s to preserve the sculpture.