Ever since the advertising mogul and collector Charles Saatchi gave the term YBA (Young British Artists) to a group of largely working-class British artists in 1992, there have been multiple failed attempts to shoehorn movements into similarly snappy acronyms. But none have failed so deplorably as the Evening Standard's Young London Artists—or YLAs—a term which surfaced in a headline this week to describe a “new wave of disruptors” said to be “refreshing London as a cultural epicentre”.

The list—which includes curators, journalists and gallerists as well as artists—is remarkable, not for the calibre of its entrants (who are undoubtedly successful), but for the debutantes, heirs and it-boys and girls it profiles without a hint of irony. Isaac Benigson is described as an “artist and socialite”, while Alaia De Santis, the daughter of swimwear designer Melissa Odabash and tech tycoon Nicolas De Santis, is “bolshy, beautiful and back in London after a year and a half in New York”. India Rose James is dubbed a gallerist but also a “platinum blonde Soho heiress” and Robin Hunter Blake, who is a regular on the London party scene, arrived to photograph the group “in velvet loafers and a taupe suit”. Then there’s Phoebe and Arthur Saatchi Yates, “the ultimate art couple” helped—as the article notes—by the fact that Phoebe Saatchi Yates is Charles Saatchi’s only child. And so the art world turns.

The article does nod to the difficulties faced by working-class people trying to make a living in the creative industries in London, and includes Nnamdi Obiekwe and Zina Vieille who, via their business VO Curations, provide affordable studio spaces to hundreds of artists. The article even begins by noting how the recent Structurally F–cked survey compiled by A-N The Artists Information Company found that artists in the public sector are paid a median of £2.60 an hour. To follow this appalling fact with such snapshots of privilege is wincing, but indicative of a culture in which we choose to ignore hard truths.

No wonder class remains a taboo subject in the art world. According to a 2018 report by Create London and Arts Emergency, just 18.2% of people in the arts are from working-class backgrounds. Alongside pay, one of the biggest structural barriers to career success is housing, a sector now in crisis 40 years after former Tory prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s ill-judged right to buy scheme. While an older generation of people were able to buy their council homes for below market price in the early 1980s, it has left millions of younger people now renting insecure and grotty accommodation, most of it bought under right to buy and now privately rented at unaffordable rates.

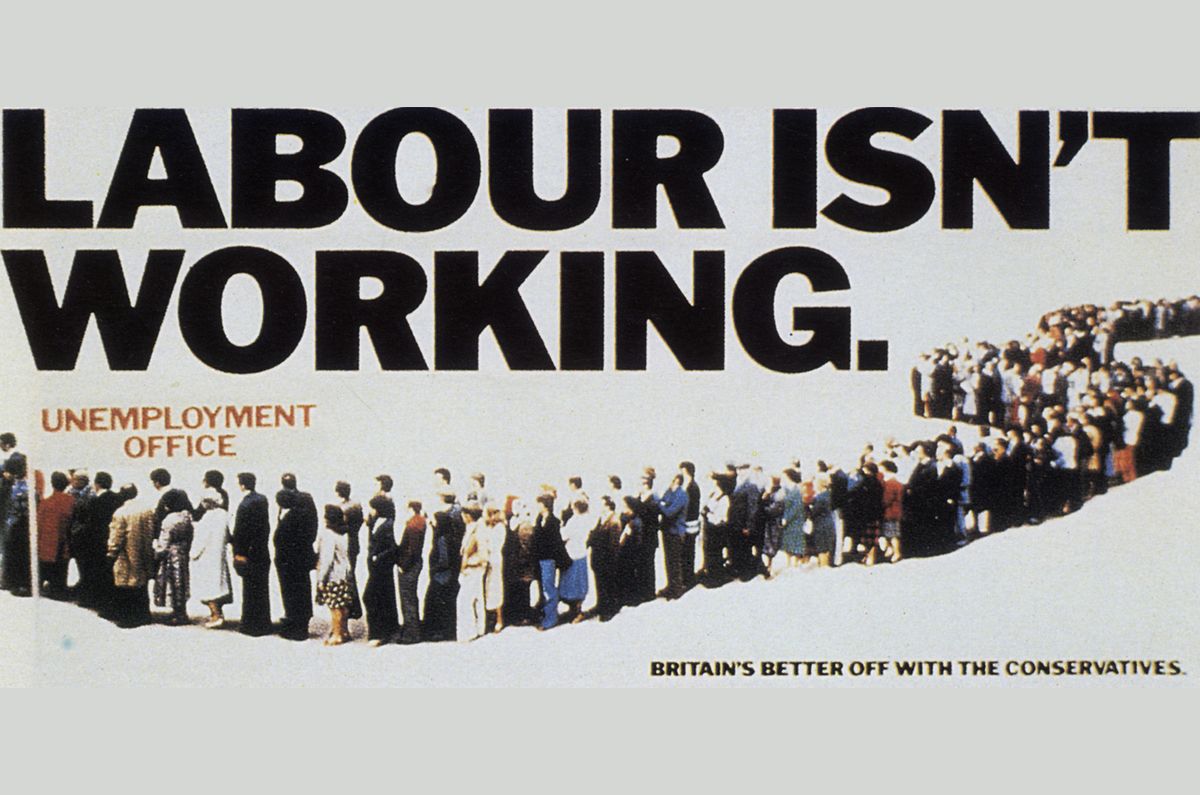

In no small twist of fate, it was Saatchi himself who helped Thatcher rocket to power in 1979 with a political poster showing a dole queue snaking out from an employment office. The strap line read: “Labour isn’t working”, and underneath, in smaller type, “Britain’s better off with the Tories”. Thatcher won a landslide election, beginning 18 years of Conservative rule.

We are now 13 years into another period of Conservative rule and the British art world is crumbling under the strains of funding cuts and a downgrading of culture. Earlier this month the Labour leader Kier Starmer finally broached the class issue, acknowledging the barriers that impede social mobility, which has gone into reverse. In a bid to combat kamikaze Tory policies to cut arts education funding by 50% to focus on “high-value subjects”, Labour has pledged that every student, irrespective of background, will have access to the arts until they are 16.

Education for all—not working harder or “going for broke”, as Phoebe Saatchi Yates implores in the article—is fundamental here. These days, the vast majority of artists are literally broke, and to peddle the myth that being more industrious will lift you out of poverty is degrading. We urgently need structural change—and the fastest way for that to happen is for those with generational wealth and invaluable social, media and political networks to help nurture the arts more widely and deeply.