The president of the Musée National Picasso in Paris has said that “completely perverse” interpretations of the life of Pablo Picasso may threaten the way he is remembered in art history.

Cécile Debray tells The Art Newspaper she is “open to any debate” regarding Picasso’s troubled relationships with women, but she also expresses concern about the ahistorical atmosphere in which Picasso’s legacy is being discussed in a post #metoo climate.

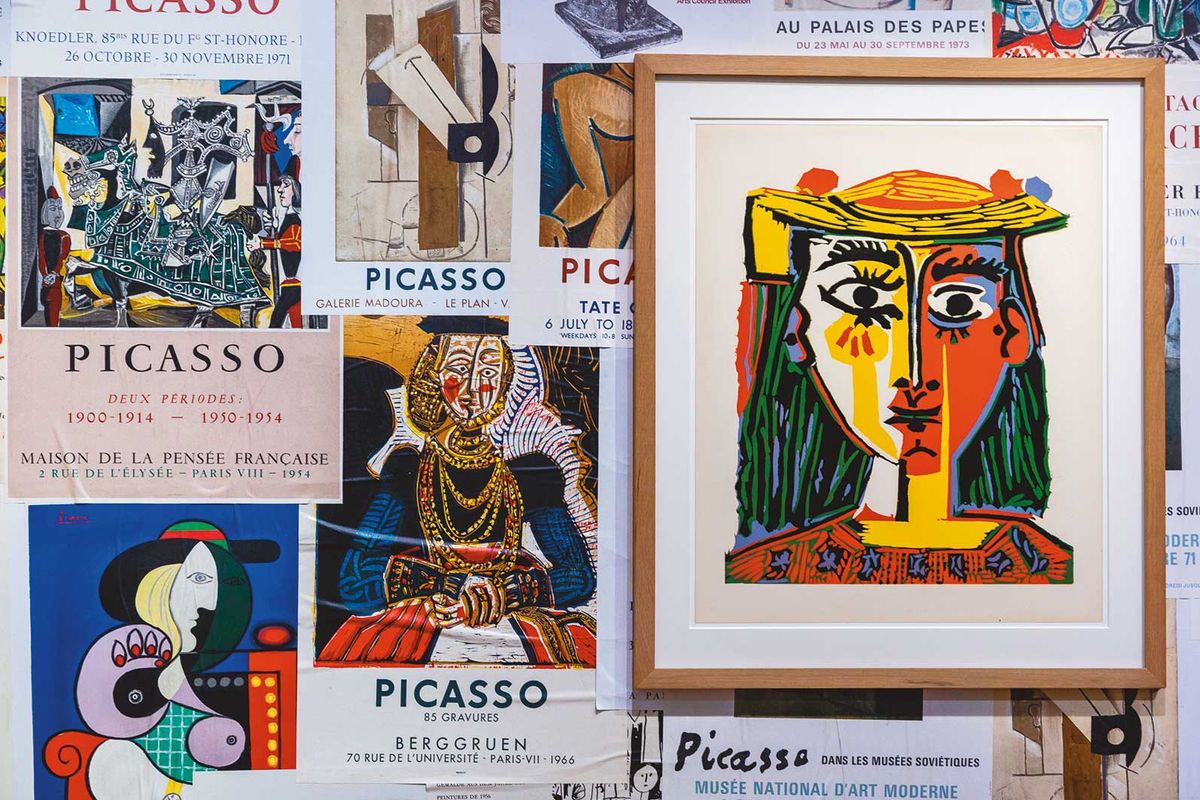

Debray’s team has spearheaded "Celebration Picasso 1973-2023", which comprises 50 exhibitions of Picasso’s work across Europe and the US to mark the 50th anniversary of the Spanish artist’s death. “We want to see how history has remembered Picasso, but we also want to look at what is true and what is not true,” Debray says. “There’s a lot of confusion about the way Picasso lived.”

Prominent critics of the artist have included Hannah Gadsby, the Australian comedian who aired their views in a televised stand-up routine, Nanette, in which they listed Picasso as analogous to the film producer Harvey Weinstein, a convicted rapist, as well as the former US president Donald Trump, the comedian Bill Cosby and the directors Woody Allen and Roman Polanski, all of whom have faced allegations of sexual abuse. “Picasso suffers from the mental illness of misogyny,” Gadsby says in Nanette.

Gadsby also opened a show in June at the Brooklyn Museum in New York, It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby (until 24 September). The show “‘reckons with complex questions around misogyny, creativity and the art-historical canon”, the museum said in a statement. Of more than 100 works on display, the show exhibits 50 paintings by Picasso, seven of which were loaned from the Musée Picasso as part of "Celebration Picasso".

But, according to Debray—who became president of the Musée Picasso in 2021, and is now in charge of the world’s largest Picasso collection—such stark readings of Picasso’s legacy have led to disinformation about the facts of his life. “Picasso did not rape [anyone],” she says. “He was not violent.” (His partner, Françoise Gilot, has said their relationship was sometimes punctuated by physical cruelty).

Responding to Picasso’s life appropriately, factually and truthfully is now “a very important fight today for everybody, in an age of populism”, Debray says. “The question of Picasso touches on some very actual problems. They remind us that works of art are not reality. And images are not the reality. Young people are often not able to deconstruct how an image is built, and how images act as representations of something imagined or fantastical.”

Picasso’s troubling relationships with numerous women throughout his life are well-documented: in a recent UnHerd article. In “How Pablo Picasso abused his muses”, the art historian Ruth Millington wrote that “while Picasso aged, his muses became ever younger”. She notes that the artist was 45 when he met Marie-Thérèse Walter, who was 17. Picasso’s paintings of her remain among his most popular; in 2021, Christie’s sold the 1932 painting Woman sitting by a window (Marie-Therese) for $103.4m.

Picasso “was a man from a certain part of Spain who was born at the end of the 19th century”, Debray says. “He was not a feminist at all. He was macho, and he was not always tender with women. These are known facts that we can discuss. But it’s very important to recall the historical context in which he lived.”

This summer, the Musée Picasso will hold a series of seminars with art students to debate how Picasso’s relationship with women should be considered in today’s age. “We want to invite people to interrogate the way the history of the work of Picasso has been written,” Debray says.

Overall, Debray wants to “open the door to new debates and new approaches” in order to make the collection applicable to audiences beyond the classic museum-going demographic. The British fashion designer Paul Smith, for example, was appointed by Debray to co-curate an exhibition of Picasso’s work as part of the museum’s anniversary celebrations. The show, Picasso Celebration: the Collection in a New Light (until 27 August), was divisive. Our critic, Ben Luke, argued in his review that Picasso’s art was sidelined, becoming mere accessories to Smith’s decoration.

A more rounded view

Debray is hopeful that the "Celebration Picasso" exhibitions provide a new generation of art-goers with a more rounded view of Picasso’s life—including the tragic events that formed him as a young man. She discusses the recent exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, Young Picasso in Paris (closed 6 August), which focused on the early works Picasso created during his introduction to Paris’s Montmartre district—“a very radical and very conceptual period for Picasso”, she says.

The exhibition detailed how Picasso first discovered Paris in the autumn of 1900, at the age of 19. He arrived with his friend, the Spanish painter Carles Casagemas, could not speak French and had spent much of his life in the small port city of Malaga, Spain.

Cécile Debray, president of the Musée Picasso in Paris, headed the Celebration Picasso 1973-2023 series

© Bernard Martinez

Picasso was mature for his age—as a teenager, he studied art in Barcelona and Madrid. Yet he found the scale of Paris overwhelming. It was the centre for art, home to Toulouse-Lautrec, who died shortly after Picasso arrived in Paris, as well as the ageing Rousseau and Renoir. Picasso quickly immersed himself in the city’s many art studios. His father, José Ruiz y Blasco, was an art teacher who had quietly developed his son’s prodigious talent, and, even as a teenager, Picasso was a far more advanced draughtsman than many of the older artists he met. He quickly found work in the down-at-heel Montmartre area, now one of Paris’s most desirable arrondissements.

The Guggenheim show includes Picasso’s early painting Le Moulin de la Galette, created in November 1900, which captures the vibrant nightlife of Montmartre. But the death of Casagemas—who shot himself in a Montmartre bar in February 1901—pushed Picasso into his Blue Period. In that intense period of grief, he depicted the night-walkers, street-dwellers, dark bars and clubs of Montmartre, capturing hedonism amid destitution and the underbelly of the city in ways never seen before.

Picasso’s rise was quick and he was soon a celebrity. In 1918, he married Olga Khokhlova, a dancer with the Ballets Russes. The reception was held at Paris’s most famed hotel, Le Meurice, near the Louvre. In the hotel’s banquet room, the Salon Pompadour, one can today see a distinct chink in a grand painting that hangs above the dining table. The blemish came from a champagne cork popped, apparently, by Picasso himself. The hotel now provides guided tours of Picasso’s impoverished beginnings in Montmartre.

The story that Picasso’s critics want to tell—the revolving door of female muses, the outsized wealth, the narcissism—is well documented. But as his legacy is taken forward, Debray believes that curators must strive to see the bigger picture. “We have to always allow the works to be re-evaluated within our time, but also to always approach his work in a new spirit, for each new era,” she says.

It’s Pablo-matic, the show in the eye of the storm

As part of Celebration Picasso, Musée Picasso lent seven works to the Brooklyn Museum for the exhibition It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby which is on until 24 September. The show, which is co-curated by the comedian Hannah Gadsby, has been at the centre of a fierce debate around contemporary interpretations of Picasso’s life and work.

Some notable commentators have leapt to the support of Gadsby. Barbara Pollock, of Hyperallergic, wrote: “The male-dominated art establishment has always used Pablo Picasso’s ‘genius’ to marginalize women. This is the only show to challenge that.”But certain negative reviews prompted Gadsby and the show’s co-curators to pose on Instagram with the caption: “That feeling when It’s Pablo-matic gets (male) art critics’ knickers in a twist”. They were primarily responding to a review by Jason Farago in The New York Times, who wrote that “the ambitions here are at Gif level” and dismissed Gadsby’s input as mostly “juvenile”.

Alex Greenberger in Artnews wrote: “[Françoise] Gilot and [Dora] Maar both produced art of note. Where was that in this show?” He added that “you can’t re-centre art history if you’re still centring Picasso”. Several critics also noted the decision to include works by contemporary female artists that referenced the likes of Matisse or Manet, rather than Picasso.

The headline of Adlan Jackson’s piece for Hell Gate got straight to the point—“Don’t Go to ‘It’s Pablo-matic’”—while Jezebel’s Kady Ruth Ashcraft concluded that the exhibition “is not the feminist achievement it wants to be”. That will surely sting.

José da Silva