“My funds are in Liverpool, not in Atlanta.” Any lover of the 1939 Hollywood classic Gone With the Wind will remember Clark Gable delivering this line. But why does Gable’s Rhett Butler, a rich socialite who spends his time lazing around on cotton plantations in the deep South of America, keep his money in Liverpool?

The answer is right there on the screen, in the clothes Gable wears. Liverpool was built on cotton.

Now, the city’s relationship with this most bloody of commodities is the subject of the Liverpool Biennial, the largest and longest running visual arts festival in the UK, the latest edition of which opens on 10 June (until 17 September).

The biennial begins at Tate Liverpool, which is built on the city’s marina and the UK’s first commercial wet dock, completed in the early 18th century. In 1759, a Liverpool newspaper ran an advertisement for an auction; the highest bidder could secure 28 bags of cotton, fresh from Jamaica. The clipping is now held in the neighbouring Merseyside Maritime Museum, for it is the first recorded example of cotton dealing in Liverpool.

The Cotton Exchange, a Grade II Listed building on Edmund Street in Liverpool, once the home of Liverpool’s cotton industry © Liverpool Biennial

By the end of the century shipments arrived at the city’s docks from Brazil, India, the Middle East and, frequently, from the port city of Charleston in the US state of South Carolina. The cotton had been handpicked by plantation slaves whose ancestors had survived the boats from Africa. The trade made Liverpool, briefly, one of the richest ports in the world.

The biennial’s title is uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things and is curated by the South African artist Khanyisile Mbongwa. "uMoya" is an isiZulu word with a multivalent meaning; it can be translated to mean spirit, soul, breath and wind.

During an opening press conference, Mbongwa set out the ambitions for uMoya. The biennial, she said, was "an attempted return of that which has been lost and taken from those who have been silenced or forgotten.” The works on show are “emancipated practices” from “histories of duress”—the work of artists who have been “displaced from their native tongue”. She defines her curatorial practice, she said, as one of “care and cure”.

Khanyisile Mbongwa, curator of the Liverpool Biennial 2023, which opens on 10 June © Bongeka Ngcobo, courtesy Liverpool Biennial

The artworks on show “require us to search our inner being,” asking the people of Liverpool “to not see themselves as an audience, but as a witness”. Alongside her curatorial practice, Mbongwa is a Sangoma; a form of shamanic, spiritual healer. She ended her address with a ritualistic isiZulu tradition that acknowledged her ancestor’s sprits.

Is there a lot of care and cure in the Liverpool Biennial? Frankly, it seems pretty punchy.

The festival features the work of 35 artists from six continents and 25 countries—15 of them have created original work commissioned for the biennial. Their work is displayed across 14 separate exhibition spaces, including what are referred to as “found venues”—makeshift exhibition spaces in vacated and derelict buildings that date back to beginnings of the cotton trade. These include the city’s Cotton Exchange, where the money exchanged hands, and the Tobacco Warehouse, once the largest brick building in the world, where the product was stored.

Torkwase Dyson's installation view of Liquid a Place (2021) at Pace Gallery ©Torkwase Dyson, courtesy Pace Gallery. Photo by Damian Griffiths

If visitors start their journey through the biennial at the Tate, then they will begin with the American artist Torkwase Dyson’s Liquid a Place (2021). These big, steel lumps, half smooth, half mottled and rusting, look as if they have sat in the water of the dock out front, weathered by the elements and only half visible, like a ship’s hull.

An adjoining label makes the explicit point that the dock—the very thing the gallery stands on—was built “to service and expedite the Transatlantic Slave Trade”. That trade, we are told, resulted in the death of 2.4 million enslaved Africans. The work, then, “examines the history and future of Black spatial liberation strategies”.

Edgar Calel, Ru k’ ox k’ob’el jun ojer etemab’el (The Echo of an AncientForm of Knowledge), 2021 © James Retief, courtesy Edgar Calel and Proyectos Ultravioleta.

Mbongwa writes alongside that Liverpool is there to be “excavated—laying bare its history of colonialism, role in the trade of enslaved people and the making of the British Empire”. Mbongwa, then, has set her stall out: we are stood, literally, on problematic ground. She wants us to come to terms with it. The spirits of the dead are alive, but unheard. We must search our inner being.

Upstairs, we find the indigenous Guatemalan artist Edgar Calel’s The Echo of an Ancient Form of Knowledge (2021). Calel’s work, without meaning to be too reductive, consists of fruit arranged on rocks. Lots of rocks, loads of fruit. Jagged lumps of sediment, carrots, celery and peppers on top. A mischievous Cattelan-esque provocation surely? Apparently not. The adjoining label tells us that Calel’s work “acts as a form of resistance in the wake of ongoing racism, social exclusion and cultural erasure of Indigenous people”.

Sandra Suubi's Samba Gown (2021) at Open Eye Gallery © Mark McNulty, courtesy of Liverpool Biennial

In Open Eye Gallery, we find the work of Saandra Suubi, a Ugandan artist working with salvaged objects, photography and performance. The series, titled Samba Gown (2021), is orientated around a flowing bridal gown, upon which messages like “women have no say in the marriage” and “men are like babies” are scrawled. On the walls, a stately African woman wears the cloak amid a landfill site; destitute people and shaggy white storks pick through the plastic waste close-by. The exhibition feels half-formed—a performance must have taken place in this forlorn location, but the photographs only hint at it. This is also, we are told from the top, “a statement of resistance”.

Close-by, David Aguacheiro, a Mozambican artist, presents the series Take Away (2018). In its centre, oil drums are piled into a small wooden boat. The sculpture is surrounded by monochrome photographic portraits that speak of loss, dislocation and disaster. The work mediates on the “disguised colonists [who] wage manufactured wars to live rich at the expense of the people,” the artist writes.

David Aguacheiro, ‘Take Away’, 2018. Liverpool Biennial 2023 at Open Eye Gallery © Mark McNulty, courtesy of Liverpool Biennial

I don’t mean to be flippant about the sincerity of marginalised or Indigenous artists. Embracing a diversity of globalised voices and working towards a better understanding of our shared histories are always, in themselves, good and righteous endeavours. Art is often a fruitful forum for discussing politics. We hold these truths to be self-evident.

But some of the art on show at the biennial is, nevertheless, problematic in its own right.

The first problem is one of fungibility. Emancipated art is today, a genre in itself; one that is becoming populated quickly as it continues to be platformed. Installations of oil drums, references to boats, woven textiles, ancestral garments, motif-heavy self-portraits—the truth is that many artists, working globally, are trading on these “histories of duress”, which means they run the risk of becoming derivative, overly literal and distinctly repetitive.

Suubi must, for her own sake, compete with contemporaries like, for example, the Black American artist Nick Cave, who has long used cloaks, textiles and clothing as a way of exploring his ancestry, identity and gender, or Rebecca Belmore—the first Indigenous artist to present Canada at the Venice Biennale, in 2005. Belmore’s cast clay sleeping bag Ishkode (Fire) (2021) stole the Whitney Biennial in 2022.

For Aguacheiro, he must try and stand shoulder to shoulder with artists like Lydia Ourahmane, who created The Third Choir (2014), an installation of drums used to transport oil from her native Algeria, almost a decade ago; it is now in Tate Britain’s permanent collection. Or how about the Johannesburg-based photographer Mohau Modisakeng, whose motif-heavy portraits of Black identity gained such attention when he represented South Africa at the Venice Biennale in 2015.

The biennial is also facing an issue of framing. When curators deal with complicated and confrontational subject matter, they often retreat under the safety net of a seemingly benign curatorial syntax. This internationally recognised lexicon, one taught at art school, often seeks to position art in ‘liminal’ states of ambiguity, or posit them as mediating on new ways of viewing. This language is, in fact, riven with cliche. And when these cliches are relied upon, when they are deployed liberally and unspecifically, they can have a crushing effect on the art on show.

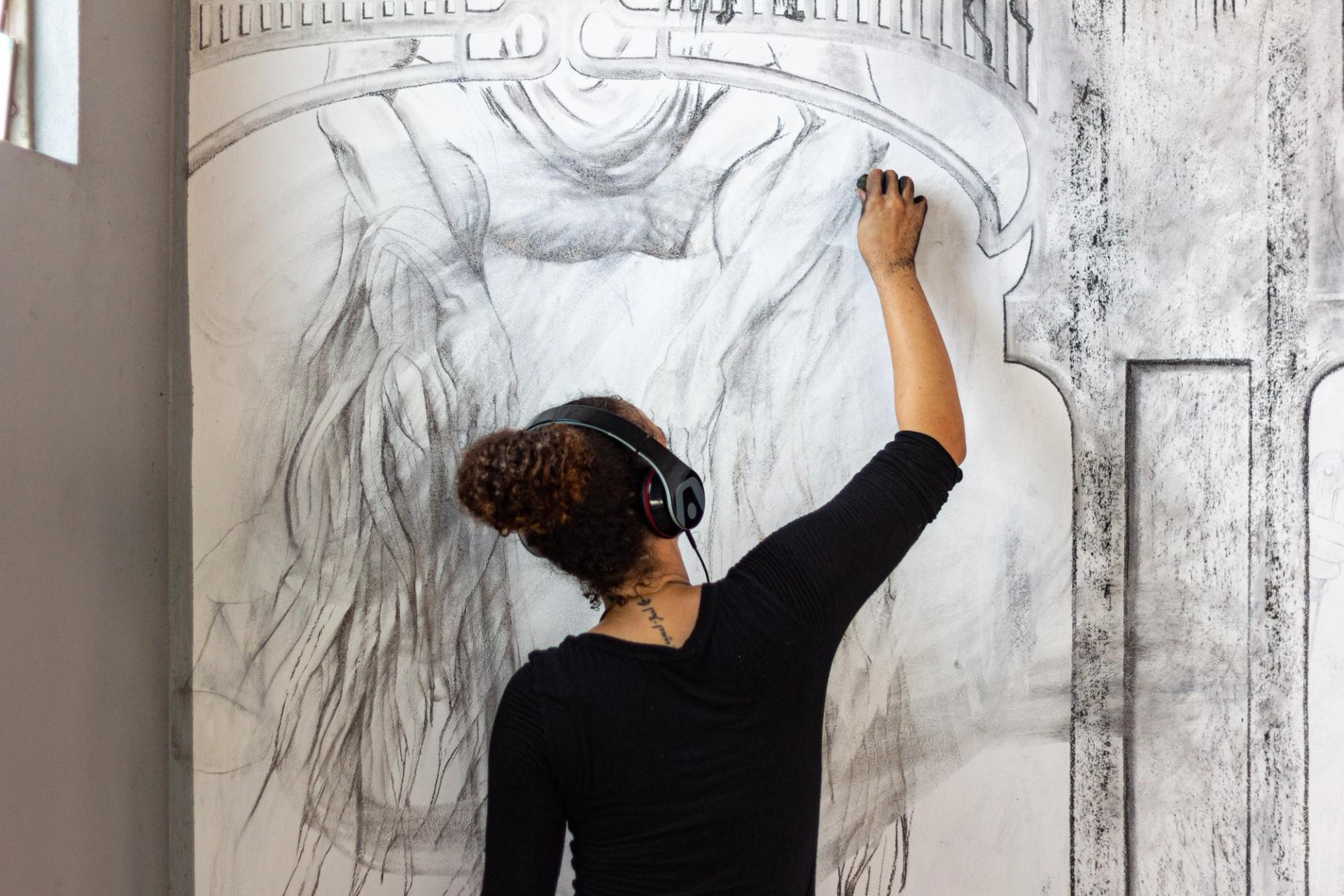

Shannon Alonzo, Subterranean Sentiments of Belonging – Cycle 2, 2021 © Ryan Lee, courtesy Shannon Alonzo, Subterranean Sentiments

This safety net is flung over many of the works at the biennial, from the strong to the weak. Shannon Alonzo’s Mangroves (2023) is a site-specific mural of Caribbean portraits, interwoven with mangrove swamps, created in charcoal in the basement of the Cotton Exchange. It is a beguiling, ghostly work from a young artist with a clear skill in draughtsmanship. Yet we’re told it is “a collective story of resistance, erasure, women’s labour, tradition and joyous celebration”. On the one hand; no kidding. But also, surely, Alonzo’s spontaneous work is so much more than this.

But, under this weight, occasionally the biennial sings. In the gardens of Liverpool Parish Church, the Nigerian artist Ranti Bam exhibits a series of curving, splitting clay sculptures; each has been created by the artist embracing the clay as it hardens before leaving it to deepen its form through its own internal physics. The series is titled Ifa (2021), a reference to the Yoruba word ‘ifá’, which means the divine, and Ìfá, which translates as ‘to draw close’.

The female form has a long history in art — but has it ever been depicted like this? The sculptures are left outside to deal with whatever Liverpool has to throw at it; the artist expresses delight when a passing bird evacuates on one.

Ranti Bam's Ifas (2023). Installation view at St Nicholas Church Gardens, Liverpool Biennial 2023 © Rob Battersby, courtesy Liverpool Biennial

The works, then, speak of youth and fertility, ageing and decay. Their presence in the garden of a House of God imbues them with questions of nature and faith. “Like our skin, they are imperfect,” Bam writes. “The Ifas pucker and crack, fold and fault with dramatic spontaneity.” That’s how to do it.

Liverpool may have been built on cotton. That legacy is still active in the city of today. But who are the modern heroes of Liverpool in 2023? The answer is: Trent Alexander-Arnold, a prodigious footballer whose grandfather emigrated from the commonwealth to make this city his home. It would be the athlete Katarina Johnson-Thompson, the daughter of a Bahamian man, or the actress Jodie Comer, a descendant of Irish immigrants. It would be Molly McCann, who overcame an abusive childhood to become a globally-recognised cage fighter. It would be Mohamed Salah, a devout Muslim raised in a tiny village in Egypt who has made Merseyside his home. The biennial struggles to acknowledge this resplendent city of today, and it should. Because, as we all know, time moves on, all too quickly.