Ilya Kabakov, the artist known for philosophical and literary depictions of life in the Soviet Union and visions of utopia expressing the desire to break free of totalitarianism, has died at the age of 89 near New York on Saturday 27 May.

An announcement sent out on behalf of his widow Emilia Kabakov and long-time collaborator did not name a cause of death.

Kabakov was born in 1933 to Iosif Bensionovitch Kabakov and Bertha Judelevna Solodukhina in what was then called Dnepropetrovsk, now Dnipro, Ukraine. His early years were defined by the Second World War, which determined his artistic trajectory. He was sent with his mother for safety to Samarkand, Uzbekistan, where he entered the Ilya Repin Leningrad Institute for Painting, Sculpture and Architecture.

After the war, he enrolled at the Surikov State Art Institute in Moscow, where he studied graphic design and book illustration, launching his official career as an illustrator of hundreds of children’s books. He was simultaneously deeply engrossed in creating unofficial art. His studio in central Moscow became the heart of the Sretensky Art Group, which included the artists Erik Bulatov and Oleg Vassiliev. It gave rise to the art movement known as Moscow Conceptualism and had an international impact despite coming from a closed society.

He left the USSR in 1987 and began working with Emilia Kanevsky, to whom he was related and had known his entire life. They married in 1992. After living in Manhattan, they created an artistic oasis on Long Island, where they lived and worked.

The Kabakovs’ work has been exhibited at top museums around the world including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Tate Modern in London and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. It was embraced but never fully understood in post-Soviet Russia both by state institutions and private collectors, shown at the State Hermitage Museum and the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art.

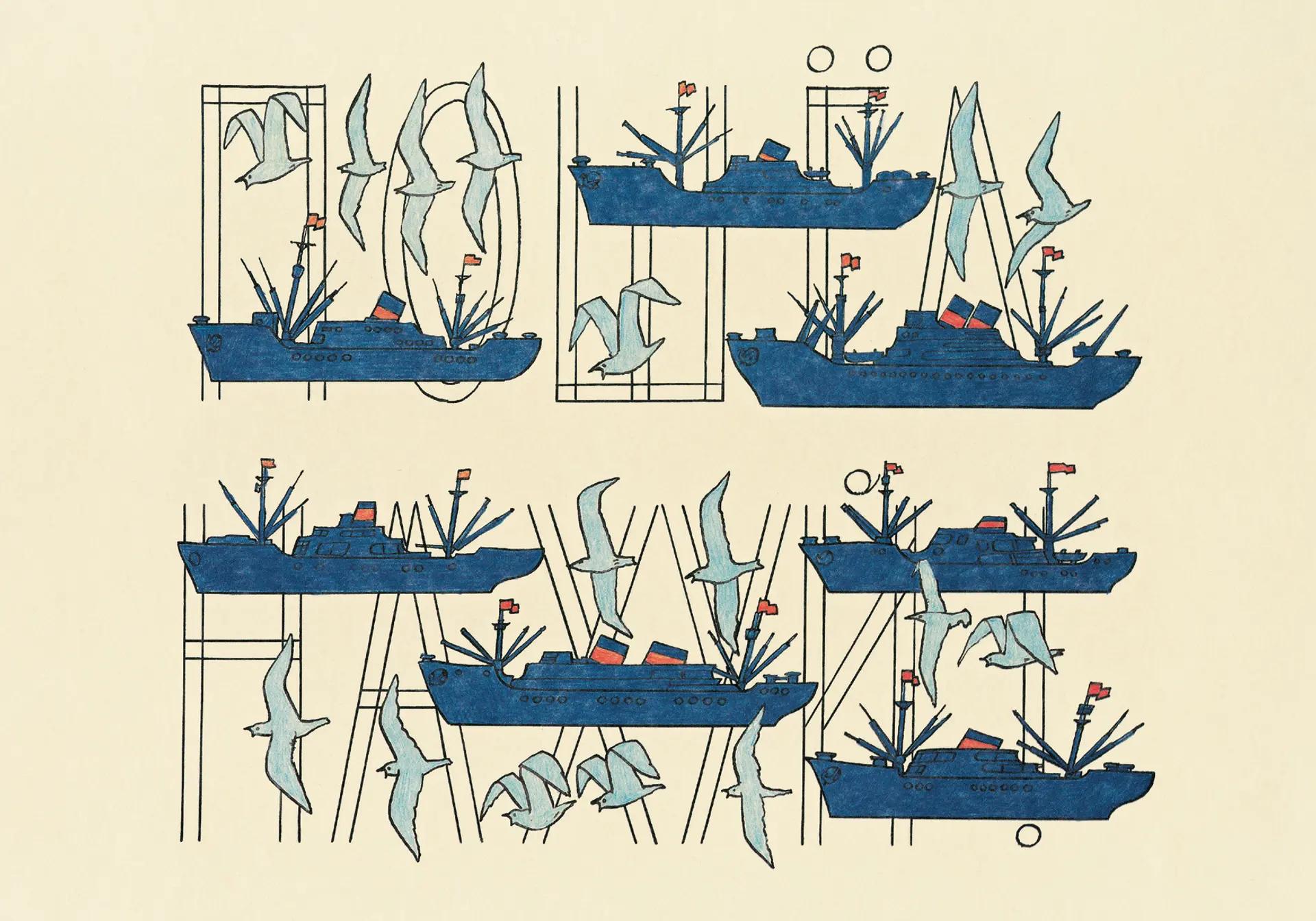

After Russia invaded Ukraine, one of Kabakov’s 1980s drawings of a ship became a meme symbolising Ukrainian resistance.

Ilya Kabakov's Ships. Go fuck yourself (1993)© Ilya & Emilia Kabakov © The Lithuanian National Museum of Art, 2022

Kabakov is most famous for “total installations”, a genre that mined his biography and served in effect as the autobiography of every “little man” living under state oppression yet reaching for the stars. The Man Who Flew Into Space From His Apartment, created in his Moscow studio in 1985 and first shown publicly at the Ronald Feldman Fine Arts in New York in 1988, depicts a devastated room in a Soviet communal apartment, with all the accoutrements of life under Communism, including political posters. The man who lived there is gone, via a huge hole in the ceiling.

Ilya Kabakov,The Man Who Flew Into Space From His Apartment (1985)

In his artist’s comment to the work, in effect his own advance obituary, Kabakov wrote of his constant desire to flee, “to run without looking back” at the moment when least expected “to jump through the window which is always closed, through the door which is most likely locked”: “

“For a long time, since earliest childhood, I have been sick of, bored, with its exhausting ‘everydayness,’ its circular movement day after day, even the very fact that it ‘is', and it’s not important whether it is pleasant, joyful, interesting, or boring, excruciating. I am simply sick of being, and I remember life as a miserable necessity. Flee from life? That never entered my head. After all, the real ‘departure’ will most likely occur on its own, in its own time, and doesn’t depend on our desire.”