The artist couple Ilya and Emilia Kabakov live and create at a home and studio on Long Island, New York. The Art Newspaper met with them there and spoke to Emilia about the often prophetic nature of art and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, where both artists were born.

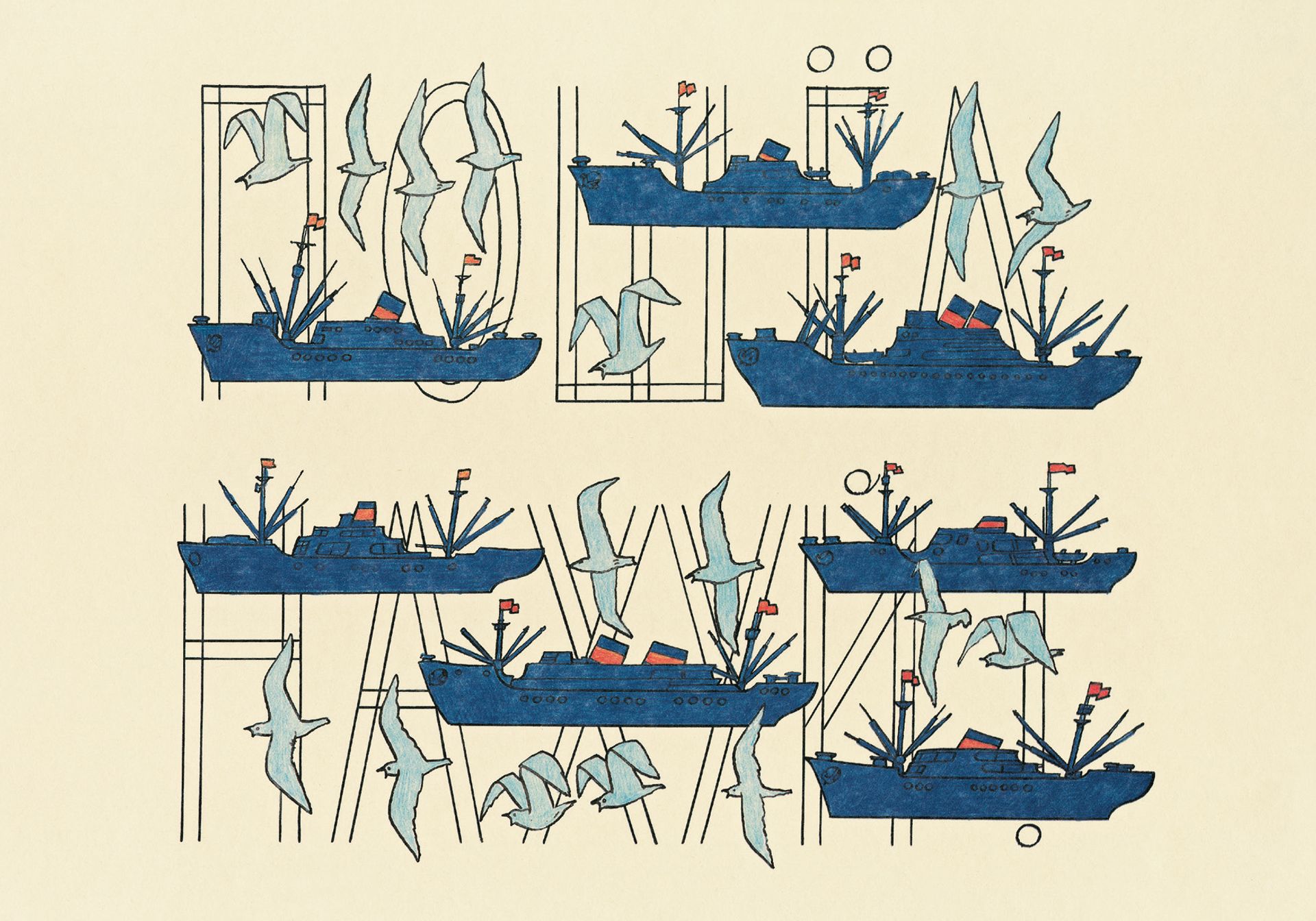

The Art Newspaper: One of Ilya’s drawings of ships, which has "go fuck yourself" written in Russian in the background, has become a sort of meme during the war in Ukraine. It has been used to represent the famous incident at Snake Island in the Black Sea in February in which defiant Ukrainian sailors declared: “Russian warship, go fuck yourself.” Ilya's image, created decades ago, began to circulate widely online after a recording of the standoff went viral. Can you tell us about that?

Emilia Kabakov: Ilya's drawing was created in 1984, and there is a whole story there. It is an album, with drawings depicting cows, rabbits, all kinds of flowers and birds. The idea is that there are children’s drawings, but there are always these “bad” words hidden behind them.

Ilya Kabakov's Ships. Go fuck yourself (1993) © Ilya & Emilia Kabakov © The Lithuanian National Museum of Art, 2022

We have a few stories about this set of drawings. A father went to the store, brought back a colouring book, and the mother saw the bad words in it. They went to the militia and there was an entire investigation into the enemies of the Soviet Union who planted such bad words in a children’s colouring book.

Ilya made these drawings in 1984, and in the 1990s we made prints, without anything like war in mind. Now it has been dug up and taken on a whole different meaning. It turns out Ilya hit the nail on the head. [Russian collector and gallerist] Marat Guelman helped get this meme started. I immediately got a call from the Lithuanian National Museum of Art [who have a collection of works by Ilya] asking for permission to publish it. We agreed, sent them the image, and they made postcards.

You have shown us a number of your works today and shared the stories of their creation. It seems like many of them are taking on a new life in connection with current events?

They have turned out to be multi-layered and many of them live on in the present day. The Red Pavilion was made for the 1993 Venice Biennale [It was designed to show that the Soviet Union never truly disappeared]. Yes, at the time Perestroika [the attempt launched by Mikhail Gorbachev to reform the Soviet system] was still happening in Russia. Everything was changing. But as the former Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin once said: “We wanted the best, but it turned out as always.”

The Red Pavilion in Venice Courtesy of the artists

It turned out that everything that Russia managed to build and change in the past 30 years disappeared overnight, and everything is returning to the same old system of repression. I’m not even mentioning the military operation [in Ukraine], which is in fact the most frightening of wars because since it seems possible that it could lead to all-out nuclear war. Everyone is on edge. The entire world has turned upside down. Why this happened, and to what end, no one knows.

The Red Pavilion has returned. We were told at the time that it would never return, that it is nonsense and we are stuck in the past. But it turns out we weren’t stuck in the past. We were looking into the future. We didn’t want this, but this is as fate would have it.

There was a time when contemporary art seemed to be accepted by the Putin regime. Do you think that was the case?

It never became an official form of art. That is an illusion. It was accepted only conditionally. Ilya and I were talking today about why they didn’t simply kill all of the underground artists in Soviet times. Almost all of them had official jobs. Half of them were members of the Union of Artists. [Erik] Bulatov, [Oleg] Vassiliev, and Ilya were all members. That is how they survived.

At the same time, they all did what they wanted. None of them were political artists. The political ones were another circle of artists. These weren’t. But each of their works was multilayered, and it turned out that many years later their work took on a different role. For example, it seems to me that some of Bulatov’s paintings from those years can now be interpreted as a glorification of Soviet images, rather than being against them. Paintings such as Bulatov’s portrait of Brezhnev have suddenly started transmitting a different message.

Ilya's works are completely different, like a prediction of the future. Those children’s ships ended up being the [Russian] military ship that was cursed at [by Ukrainian sailors]. That’s not what he had in mind. When we made The Red Pavilion, we thought that the USSR would return, but we did hope that it would not happen. Thirty years later it is here again. It was a fantasy, but also a fear of the return of the USSR, of the totalitarian regime.

We don’t believe that it’s possible to build a democratic future there. Utopia is a word that cannot be brought to life, especially in such a country as Russia, because there is a certain kind of inertia. On the one hand there are many incredibly talented people. On the other hand this is a country that time and again, after certain intervals, tosses out or destroys these talents. This happened with the revolution. It happened in 1937 and after the Second World War when a huge number of people remained in the West, left the Soviet Union, died, or were imprisoned again. And this is happening now.

It seemed like things had relaxed and that something new had begun. Bridges of friendship were built, museums exchanged knowledge and practices, Russians went to work abroad, specialists came to Russia. Something was being done. And now suddenly it all falls into an abyss. For a very long period of time Russia will become an aggressor, the enemy of humanity. For what? When one country completely destroys another, with no regard for victims, it also suffers and dies. That is what is happening now. Both Ukraine and Russia have been destroyed.

There are many painful discussions on social media right now between Ukrainian and Russian curators about whether Russian art has the right to speak after the invasion of Ukraine. How is this dividing the art world?

On the one hand I understand [the Ukrainian perspective]. I was recently told that I am not speaking enough about the suffering in Ukraine. For me, any war—any killing of men, women and children—is unacceptable in any country, whether it is Israel, Palestine, Iraq or Afghanistan. Russia and Ukraine all the more, the two countries in which I have lived, from which I am from. But I came from a country, the Soviet Union, in which everyone pretended to get along. I’m not referring to the totalitarian system, which is the reason I left, never returned and would never return. I wouldn’t return for any reason, whatever I may be offered, because unconsciously I always feared everything could repeat itself. And that’s exactly what is happening now.

Inside the Kabakov's New York studio Photo courtesy of Sophia Kishkovsky

Art must unite people. Art does not belong to Ukraine or to Russia. Culture must be protected by everyone. Cultural memory and cultural heritage are what distinguish us from animals. Now it is being destroyed from both sides. It is physically being destroyed by Russians in Ukraine. I’d like to say that it’s not Russians but some mercenaries, but I’m afraid that Russians are also actively participating in those massacres. The cultural heritage of another nation is being destroyed. No one wants to understand this, but those who do are leaving Russia today. Many people in Russia don’t want to believe or understand what is going on.

What will happen with the Russian art world?

I read that apartment exhibitions are being held again in small cities around Russia. Artists bring their paintings and invite people to see them for free. We’ve returned to Moscow of the 1960s and 70s. Things have come full circle. It means unofficial art will appear again. We will get a new unofficial world of Kabakovs, Bulatovs, Vassilievs, Komars and Melamids and many others.

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov's The Ship of Tolerance (2005-ongoing) in Miami in 2011. The project involves collaborating with schoolchildren, who make paintings based on the meaning of tolerance that are then combined to make the sail of a ship Courtesy of the artists

I received a very interesting email today from a Moscow artist who has two sons and will probably be forced to leave Russia because he has put together an exhibition of portraits of people who were arrested. He asked me what to do. I said he has to think of his children as they will suffer. He said he’s read all of the interviews Ilya and I have given and everything we’ve written because he wants to understand how to create multi-level works in which it’s not always possible to recognise what’s inside—for them not to be obviously anti-government. My answer is that art must always be like this. It can’t be direct or unilinear, it must be complex. People are not so simple. There is no black and white. We are very multi-layered people. That is what makes us people.

The problem is that all of the truly talented artists have left. They are all known here, but they are not there. A very interesting article came out recently in a Russian publication about “100 living Russian artists you should know.” It says “Ilya Kabakov still holds the title of number one Russian artist". I think they might have rushed to claim him as a Russian artist so that Ukraine doesn’t lay claim to him.

But I would like to repeat what I said before: We consider ourselves international artists, born in the Soviet Union and living in the United States of America.