Johannes Vermeer had only been rediscovered a few years earlier in Van Gogh’s time—but Vincent and his brother Theo were early enthusiasts. Théophile Thoré-Bürger, the French critic who made the Delft master famous, published his catalogue in 1866, when the two Van Gogh brothers were boys.

Johannes Vermeer’s View of Delft (1660-61)

Credit: Mauritshuis, The Hague

Vincent’s favourite Vermeer was View of Delft (1660-61), which he saw in the Mauritshuis when he was living in The Hague. In hospital in June 1882, while being treated for gonorrhoea, he wrote to Theo: “The view from the window of the ward is splendid to me: wharves, the canal with potato barges, the backs of houses being demolished, with workers, a bit of garden and in the next, more distant plane the quay with the row of trees and lamp-posts, a complicated court with its gardens, and also all the roofs, all seen in a bird’s-eye view.”

He went on to compare the light effects he saw from the window of the crowded ward with those in Vermeer’s atmospheric painting. While suffering a painful treatment, dreaming of View of Delft comforted him.

Three years later he again wrote about View of Delft, telling Theo that “when one sees it from close to, the townscape in The Hague [at the Mauritshuis] is incredible, and done with completely different colours from what one would suppose a few steps away [from the painting]”.

Johannes Vermeer’s Woman in Blue reading a Letter (1662-64)

Credit: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In July 1888, while living in Arles, Vincent wrote to his artist friend Emile Bernard about Woman in blue reading a Letter (1662-64) at Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum: “Do you know a painter called Vermeer, who, for example, painted a very beautiful Dutch lady, pregnant? This strange painter’s palette is blue, lemon yellow, pearl grey, black, white. Of course, in his few paintings there are, if it comes to it, all the riches of a complete palette.”

Well over a century after Van Gogh’s time, there is still a debate over whether the woman was pregnant or not. The catalogue for the current Rijksmuseum exhibition comments: “Much thought has been given to whether the amply cut piece of clothing is a clear sign of the woman being pregnant. As the garment itself does not provide a clear answer, the speculation will continue—which is perhaps just what Vermeer intended.”

Two months later Vincent returned to View of Delft in a letter to Theo, comparing Vermeer’s townscape to Arles and its surroundings under the Provençal light: “Nature here is extraordinarily beautiful. Everything and everywhere. The dome of the sky is a wonderful blue, the sun has a pale sulphur radiance, and it’s soft and charming, like the combination of celestial blues and yellows in paintings by Vermeer of Delft. I can’t paint as beautifully as that, but it absorbs me so much that I let myself go without thinking about any rule.”

Vermeer helped give Van Gogh the confidence to break the rules of conventional art. After discussing the Delft master he immediately went on to give some examples of his own recent work, including the four versions of Sunflowers which he had just completed a few weeks earlier. Of course Van Gogh’s work is completely different from Vermeer’s, but both artists broke new ground.

Johannes Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid (1664–67) and Woman writing a Letter, with her Maid (1670–72)

Credit: Frick Collection, New York (photograph: Michael Bodycomb) and National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

What has not been appreciated is that the Paris gallery where Theo worked, Boussod & Valadon, may well have helped sell two Vermeers: Mistress and Maid (1664–67) and Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid (1670–72).

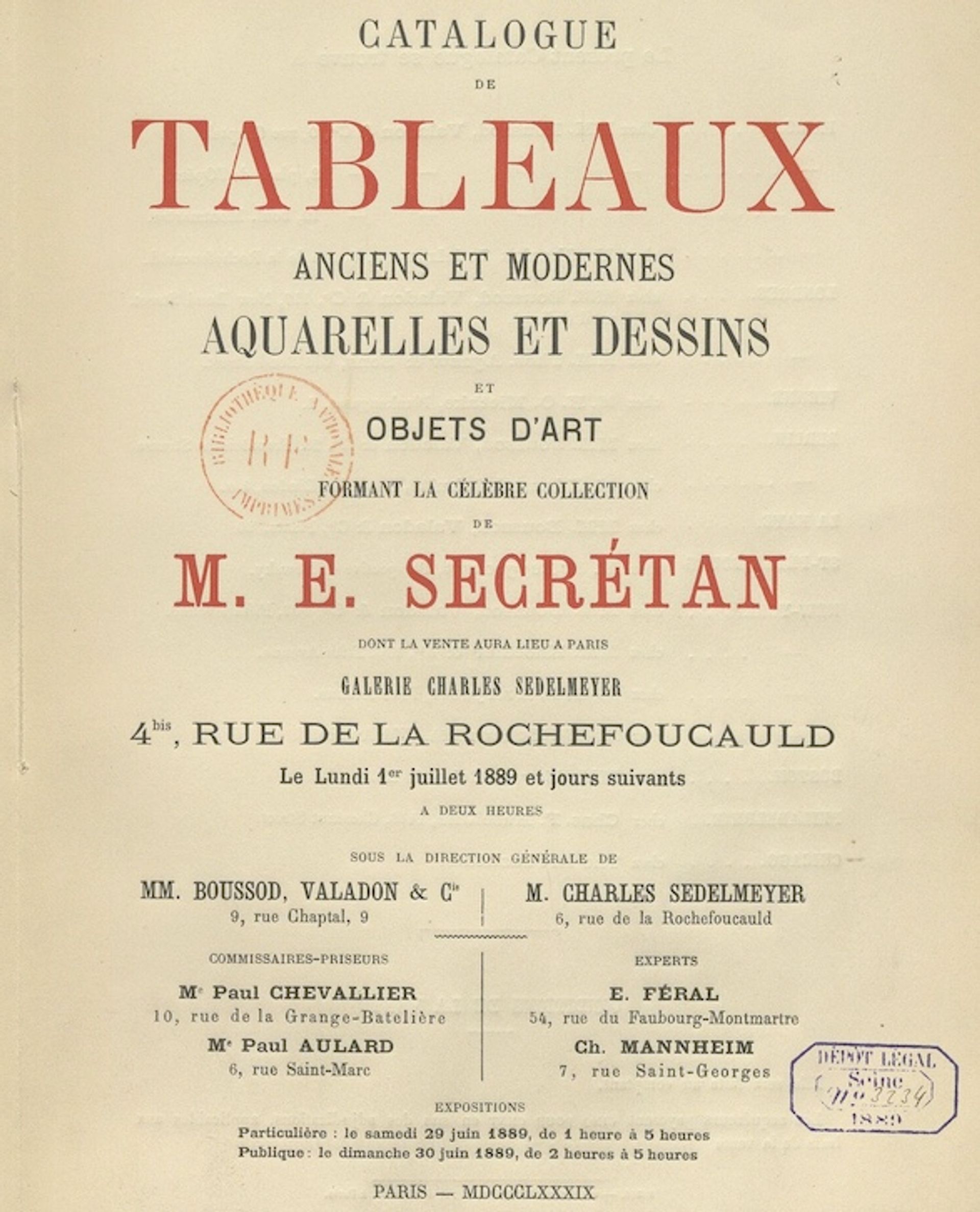

In July 1889 Boussod & Valadon was one of the two firms involved in the auction of the famed collection of Etienne Secrétan, the wealthy owner of a copper foundry. The sale was held at the Charles Sedelmeyer gallery, but with assistance from Boussod & Valadon, as it recorded on the cover of the catalogue.

Cover of the Etienne Secrétan action catalogue, 1 July 1889, noting the involvement of Boussod & Valadon

Theo was heavily involved in the sale. His wife Jo wrote to her family about the scene outside the auctioneers: “The whole street full of vehicles – unbearably hot inside and naturally a sea of people ... I shall be glad for Theo when it’s all over, for he is extremely busy.” A few days later she sent a letter to Vincent, saying that Theo “has been caused a great deal of fatigue by that Secrétan sale”.

Theo, the manager of the Boussod & Valadon branch in Boulevard Montmartre, dealt largely with 19th-century art, so it is unclear whether he was directly involved with the two Vermeers. But he would certainly have seen the paintings at close hand.

Both Vermeers sold: Mistress and Maid to the Russian statesman Alexander Polovstov (now in the Frick Collection, New York) and Woman writing a Letter, with her Maid to the Paris-based Marinoni collection (now at the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin).

Johannes Vermeer’s The Lacemaker (1666–70)

Credit: Musée du Louvre, Paris

In February 1890, after Vincent had moved to the asylum on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Theo wrote about a visit to the Louvre that he had just made with their sister Wil. Theo told his brother that The Lacemaker (1666-70) had been moved since they had seen it together two or three years earlier, when Vincent was living with him in Paris. It was now hanging at eye level, so the details of this jewel-like canvas could be better appreciated.

Both Van Gogh brothers appear to have been equally enthusiastic about Vermeer. The Delft artist’s popularity has rocketed since their day, witness the sold-out retrospective at the Rijksmuseum. Two of the world’s half dozen most popular artists are now Dutchmen, both with surnames beginning with V.

Other Van Gogh news:

Van Gogh’s Pensioner drinking Coffee (November 1882)

Credit: Burgersdijk & Niermans, Leiden

Pensioner drinking Coffee (November 1882), an extremely rare print by Van Gogh, is coming up for sale. The lithograph is being offered on 10 May by Leiden-based Burgersdijk & Niermans, with an estimate of €80,000.

Only three impressions of this print are known, two of which are at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum. This third example was given by Van Gogh to his artist friend Anton van Rappard. After later passing through the d'Audretsch gallery in The Hague it has been in the same family for nearly a century.

The print depicts Adrianus Jacobus Zuyderland, who was living in an almshouse in The Hague where Van Gogh regularly went to sketch its elderly residents. Zuyderland, then aged 72, was his favourite model.

Sotheby’s offered what was cataloged as another version of Pensioner drinking Coffee on 20 April 2016 in New York. The estimate was $180,000-$200,000. It turned out that the Sotheby’s print was not authentic, and was merely a later reproduction—- and it was withdrawn before the auction.