Chris Burden’s Urban Light (2008), one of the best-known and most beloved art installations at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma), is about to get a new paint job to help protect it from the very public displays of affection bestowed on it every day.

The eye-catching installation of 202 historic streetlamps, sited prominently on Wilshire Boulevard, is one of 23 projects funded as part of Bank of America’s (BOA) annual art conservation grant programme this year. According to the bank, “conservators will apply protective paint layers that have been extensively tested on all the streetlamps, ensuring that substances such as lipstick, permanent marker and dye can be easily cleaned from their surfaces”.

“The work gets a lot of attention from the general public—and that’s what’s intended,” Brian Siegel, Bank of America’s global arts and heritage executive, tells The Art Newspaper of the work’s selection as a grant recipient. “When the museum started telling us about the work that needed to be done, we thought it’s just such a great example of art being accessible to people. In so many cases, you see something up on the wall, and you can’t physically interact with it. With this project, anything that was going to help the durability of it, and allow for that continued engagement, was great.” The work was previously restored in 2016.

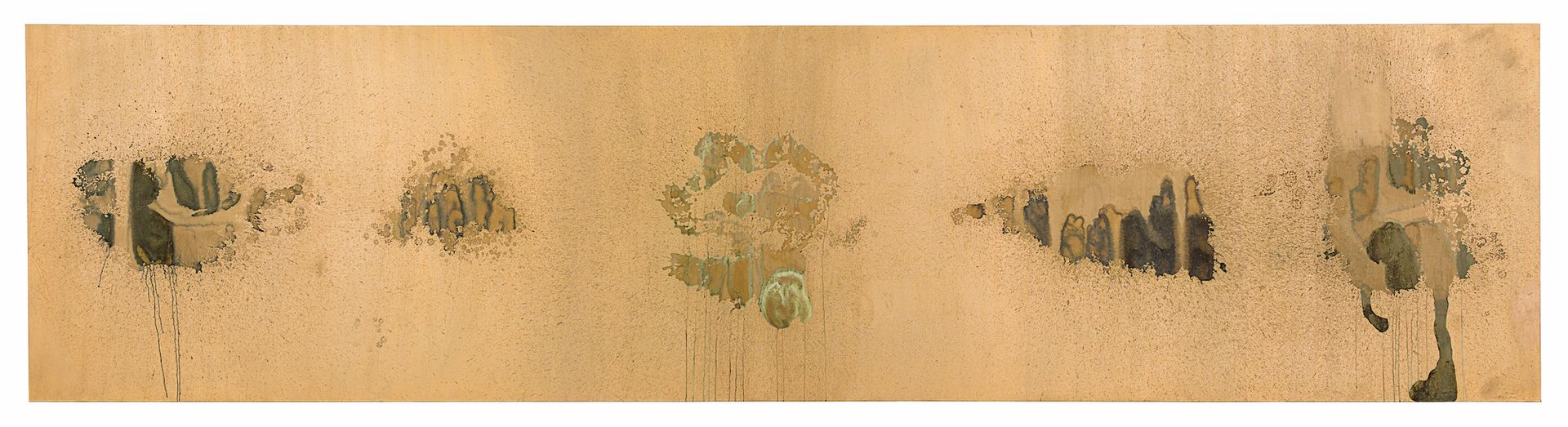

Another institution that will receive funding from BOA is the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, to study and preserve Oxidation (1978), one of the Pop Artist’s under-researched “piss paintings”. These works were made using a reactive copper acrylic paint, and the artist would then have friends and assistants urinate on the canvas, creating abstract and improvised splash patterns. According to the bank, the largest example of this series in the museum’s collection was exposed to high temperatures and humidity in June 2020 (while the museum was closed to the public during the pandemic), “causing drips of liquid to seep from within the canvas and new corrosion patterns to emerge”. Due to its size, the work will be conserved in the gallery, allowing the public to learn about the science and technology behind the project.

Andy Warhol, Oxidation, 1978 The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

The bank’s conservation programme “focuses on all different types of art. Museums may find it challenging at times, because they don’t always know what to submit or what might get funded,” Siegel says. “But when you think about, what is culture, what is art? This happens to be something unique, that obviously is important to the museum, and that they want to understand better and preserve. And the scholarship that they’ll acquire from doing this will be able to be passed on to other museums and institutions who have similar works. That’s what the programme is really designed to do.”

Other projects to receive funding include a trio of portraits of Hawaiian royalty at the Hawai‘i State Archives in Honolulu, a Friendship Totem by the Nisga’a First Nations artist Norman Tait at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, a group of 98 photo albums by the Lebanese photographer Agop Kouyoumjian at the Arab Image Foundation in Beirut, a series of 29 works on paper by the muralist John T. Biggers at the Hampton University Museum in Virginia, and a collection of946 gold and silver objects at the Hong Kong Palace Museum Collection.

Over the past 13 years, BOA’s art conservation programme has funded 237 projects in 40 countries around the world. The bank is also a major sponsor of museum exhibitions, and has run a popular Museums on Us initiative, which provides free admission to 225 museums around the US for its credit and debit card holders.

Siegel, who has worked at the bank for more than 15 years, took over as global arts and heritage executive last year, following the retirement of long-time leader Rena De Sisto. Siegel hopes to build on the foundation of corporate support and “cultural sustainability” that De Sisto started by expanding on some of the bank’s funding opportunities, including in art conservation. One example of this is a new internship program, run in conjunction with the University of Delaware and the Alliance of HBCU Museums and Galleries, that will give ten students from historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), who have already completed an undergraduate course in art conservation, a paid internship at a major institution.

“When you think about the field of art conservation, it’s important for us not just to fund the project, but also to look at the future workforce,” Siegel says. The programme is just starting to sort through applications and will select its first group of interns this summer.

The bank is also working with the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative, to support emergency preservation of heritage at risk from armed conflict or natural disasters, including through its Army Monuments Officer Training & Military programme, a modern-day version of the Monuments Men and Women who were deployed to preserve art collections across Europe during the Second World War.

“The military is focused on making sure that our officers and our allies understand important cultural sites,” Siegel says, “so that they can take a more proactive approach in protecting culture.”