The Copenhagen painter Vilhelm Hammershøi had his most productive period between 1898 and 1908 when he lived and worked in an upper-floor apartment in a 17th-century building, in his hometown’s Christianshavn neighbourhood. Here he created the works that he is now best known for—ethereal, enigmatic interior scenes, typically set in that apartment, which have helped to make him the most expensive Danish artist at auction, with three sales exceeding $5m since 2017. Now that market will be tested again, when a key work from those years comes up for auction at the 16 May Modern art evening sale at Sotheby’s New York.

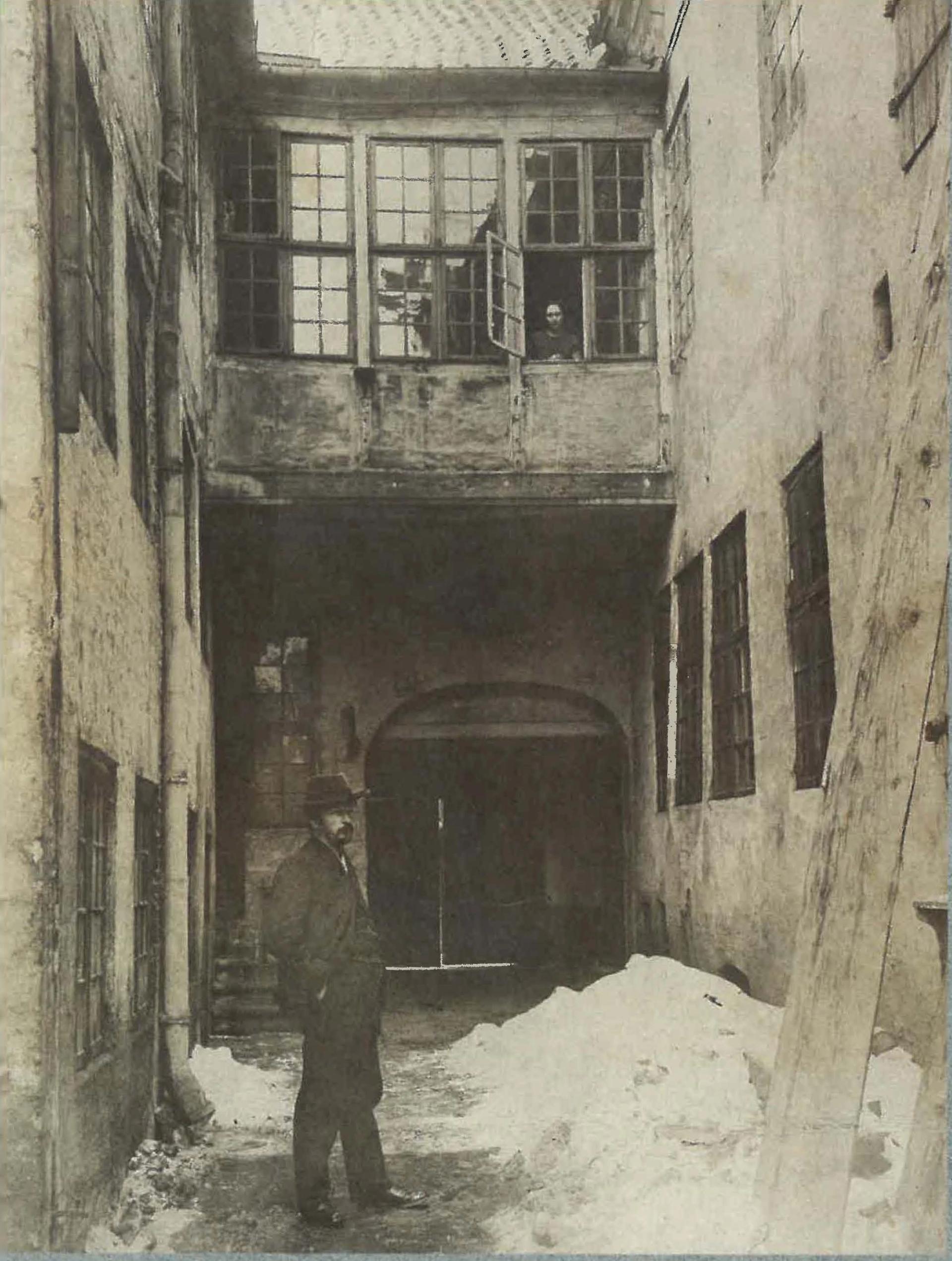

Vilhelm Hammershøi outside Strandgade 30, with his wife Ida at the window Image: Courtesy of Sotheby's

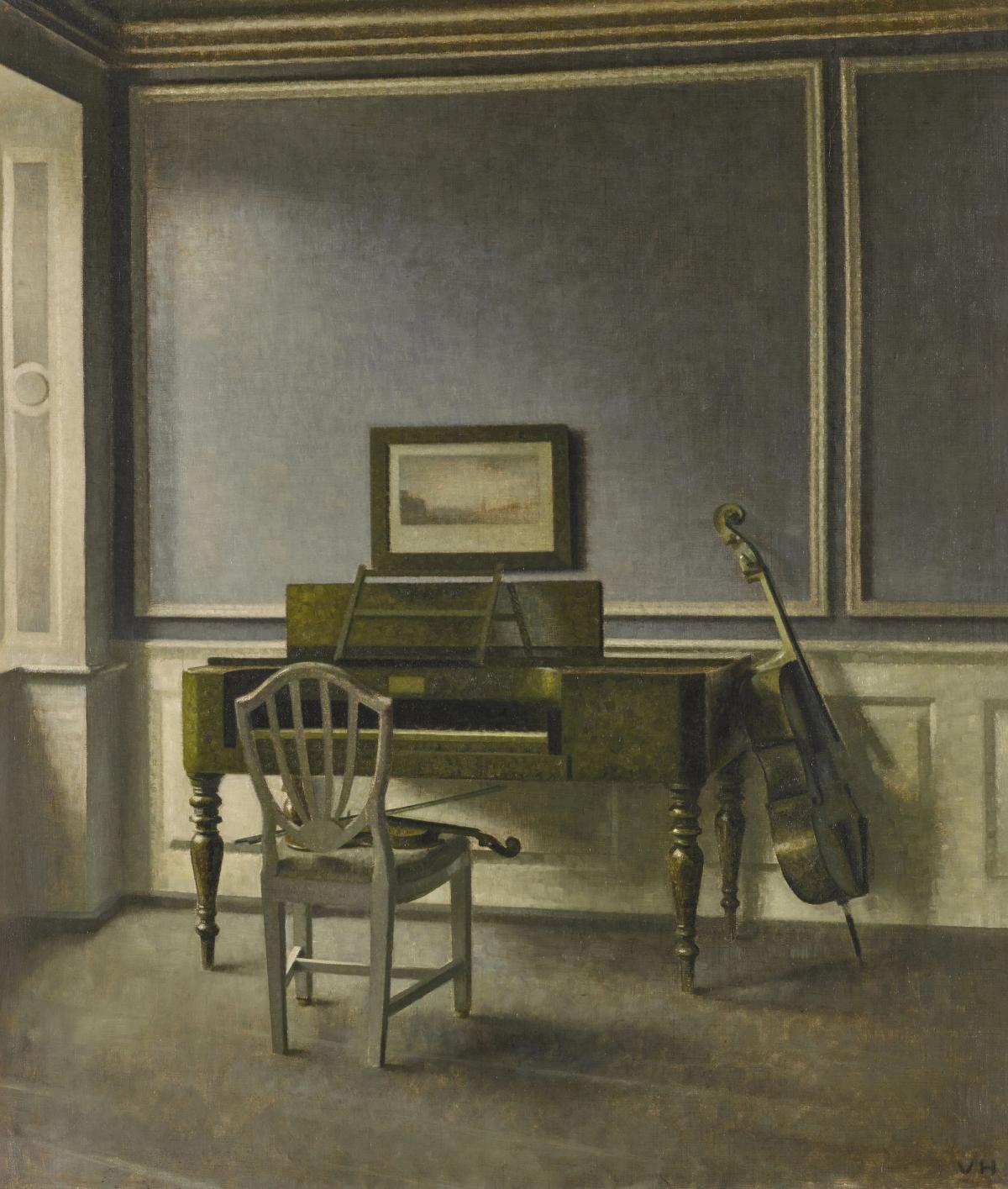

Interior. The Music Room, Strandgade 30, painted in 1907, last changed hands in 1944, when the grandparents of the current owners bought it at a Copenhagen sale. As it happens, they also lived in the very same apartment which Hammershøi inhabited when he was in his prime, and they managed to place it on the same wall depicted in the painting, where it has been hanging ever since.

Interior. The Music Room, Strandgade 30 is a spare, nearly ghostly work, showing a trio of musical instruments seemingly set aside, or even abandoned, in a room overlooking the street. The painting has occasionally been lent to exhibitions, including the breakthrough 1997-98 touring show, whose venues included Paris’s Musée d’Orsay and New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Critics and collectors now regard that show as decisive in the artist’s emergence as an artist of international standing.

In May 2022, the top price for the artist at auction was reached, when another work from the Strandgade 30 period was part of the Christie’s New York sale of the collection of the Texas philanthropist Anne Bass. Stue (Interior with an Oval Mirror) sold for $6.3m, following a pre-sale estimate of $1.5m-$2.5m. Interior. The Music Room, Strandgade 30, which will be previewed in Sotheby’s London showroom from 12-16 April, will have an estimate of $3m-$5m million—the highest ever for a Danish work.

The painting has long been on Sotheby’s radar, says Claude Piening, the senior international specialist in European art at Sotheby’s London. “We have known the painting for many years,” he says, alluding to dealings with two generations of the work’s owners. And the apartment itself is a legendary venue to local Hammershøi experts, says Gertrud Oelsner, the director of Copenhagen’s Hirschsprung Collection, known for its Hammershøi holdings, who counts herself as one of the few who have managed actually to visit.

Strandgade 30 dates back to the 1630s, and the artist “needed the old building,” Oelsner says, to inspire him. Unlike most local artists at the time, she says, Hammershøi did without a studio, choosing to paint at home, with the centuries-old atmosphere contributing both subject matter and the right working environment. When Strandgade 30 underwent a renovation, he and his wife, who were renting, were forced to relocate, and the artist died in 1916, when he was only 51.

The equivocal, even uncanny aspects of Hammershøi’s art point ahead to a modern sensibility, but scholars tend to place him firmly in a 19th-century tradition, regardless of the 20th-century dates of many of his signature interiors.

In 2018, the Getty paid $5m for Hammershøi’s Interior with an Easel, Bredgade 25, depicting his penultimate home—this time, in the centre of Copenhagen. The museum takes as its mission collecting works up to 1900, but “we pushed this boundary a little bit” for the work, says Davide Gasparotto, Getty’s senior curator of paintings.

Sotheby’s says it has alerted a small group of potential buyers for Interior. The Music Room, Strandgade 30 ahead of today’s announcement of the sale. (“Some people need time to get their finances lined up,” explains a Sotheby’s spokesperson.) But Gasparotto, speaking early this week, says he has not been made aware of any important Hammershøi works coming up for auction. “For us, we have one and I think one is probably enough—it will be the one.”