Back in the 1980s, the influential American political scientist Joseph Nye pioneered the concept of “soft power” that was adopted by both the Clinton and Obama administrations. Culture was one of the subtler agencies that could persuade, rather than coerce, other countries to come round to America’s way of thinking.

Since then, consciously or not, such neo-colonial notions of soft power have underpinned the global ambitions of many of the West’s most influential players in the institutional and commercial art world. Art has the power to “transcend borders and create meaningful connections between peoples”, according to Softpower30, an index that ranks nations by cultural influence (something that statisticians generally agree is impossible to quantify), compiled by Portland, a UK-based strategic communications agency.

As the French street artist JR says, in a much-repeated quote that sums up the belief system that has for so long underpinned the West’s visual arts culture: “Art can change the way we see the world.”

But will the 21st century see the liberal West’s much-vaunted soft power of art be compromised, if not neutralised, by the hard power of nations that think differently about human rights and democracy?

Arts programmes

Last month we learned that the French government agency Afalula is launching art programmes in the AlUla region of Saudi Arabia. In addition, experts from the Centre Pompidou in Paris will advise on the creation of a new museum in this north-western part of the country.

At the same time, we also learned that between 2015 and 2022, an average of 129 executions were carried out each year in Saudi Arabia, an 82% increase on the period 2010-14, according to a report compiled by the European Saudi Organisation for Human Rights and the campaigning non-profit Reprieve. In 2022, no fewer than 147 people were put to death, 90 of them for non-violent offences.

This uptick in state-administered violence has occurred during the supposedly “reforming” rule of the Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, or MBS, who seized power in 2017. Shortly after becoming crown prince, MBS announced at an international business conference in Riyadh that he and his citizens “want to live a normal life. A life in which our religion translates to tolerance, to our traditions of kindness.”

The following year, MBS authorised the murder of the Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi, according to evidence gathered by US intelligence agencies. Also deeply problematic is Saudi Arabia’s role in leading a coalition, backed by the US and the UK, against Houthi rebels in the ongoing war in Yemen.

A vision of a more “normal” life in Saudi Arabia will be realised by a AlUla residency programme in which artists will tactfully explore themes such as “agriculture, botany and perfume”, according to Afalula, the agency guiding the scheme.

Iwona Blazwick, the former director of London's Whitechapel Gallery, is chair of the Saudi-based expert panel overseeing the AlUla residency programme. Currently said to be buying up art from galleries in the UK, she says one of the main ambitions behind the Saudi initiative is to “create dialogue that transcends geo-politics”. She, too, believes “art can change society”.

As Blazwick has previously pointed out, human rights are under threat in other parts of the world too, not least the US and the UK. The artist Jake Chapman further challenges the moral assumption that only the West can wield its soft power. “The main reason people are finding a Saudi Beaubourg so objectionable is that we are delighted to be cultural imperialists when our implicit values are being honoured, but we are less happy when it feels like monetised cultural appropriation,” he says.

Augustine Paredes is a multi-disciplinary artist and one of six artists selected for French government agency Afalula’s residency programme in the AlUla region of Saudi Arabia

Courtesy of the artist

“It seems to me that the buying power of Saudi Arabia, for instance, is appropriating our culture without honouring its imperialist conditions, and it signifies something more sinister—not humanitarian crimes—but that our soft power has become powerless.”

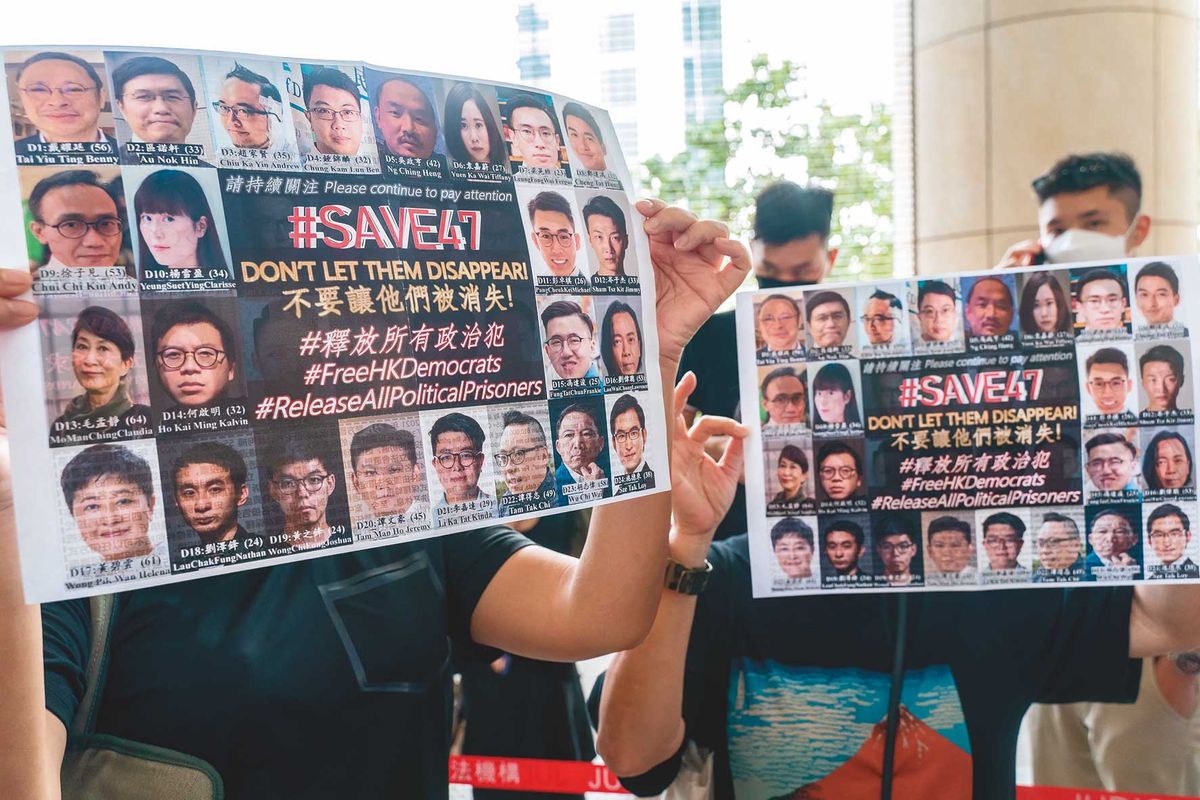

Another case in point is Hong Kong, which is categorised as “partly free” by the Washington DC-based non-profit Freedom House. That categorisation is unlikely to improve now that the Chinese authorities have started trials of the so-called “Hong Kong 47” group of pro-democracy activists, charged with conspiracy to subvert state power.

Putting nobody off

Yet the world’s top art dealers and auction houses remain ever eager to do business in the region. On 21 March, Art Basel will begin previews of its biggest Hong Kong show since 2019, featuring 177 galleries from 32 countries, chomping at the bit to tap the wealth of the world’s second biggest economy, even if it is an authoritarian regime.

The international auction houses remain gung-ho about expanding their footprints in Hong Kong. Sotheby’s is opening a new 24,000 square-foot space in central Hong Kong’s luxury district in 2024. Late last year, Phillips relocated its Asian headquarters to a six-floor 48,000 square-foot headquarters in the city’s West Kowloon Cultural District. Christie’s is planning a fourfold expansion of its Hong Kong operation into 50,000 square feet of a new Zaha Hadid-designed skyscraper, due to be completed this year.

When asked whether they had an official response to counter criticisms of their expansionism in an anti-democratic territory such as Hong Kong, Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips all declined to comment. Art Basel also declined to comment specifically on the suppression of democracy in the special administrative region.

It seems that, as far as many people in the international art world are concerned, what they are doing—whether they are making, curating or simply selling the stuff—is above political concerns, unless there are official sanctions in place, as is the case with Russia.

Western-style contemporary art can introduce its soft power to new territory after new territory, just so long as it doesn’t question the real power running those territories. But then if that happens, who is changing whom?

Over the centuries there have been any number of explanations as to why art is a good thing for human beings. Has the 21st century added a less elevated one to the list? Art adds a useful sheen to authoritarian regimes.

Dating from the late Neolithic period, the Thornborough Henges are now legally owned by Historic England as part of the National Heritage Collection

Courtesy A.P.S. (UK)/Alamy Stock Photo

The persuasive power of two million tonnes of grit

The headlines characterised it as a generously unrestricted act of corporate donation. The construction firm Tarmac has given the forgotten “Stonehenge of the North” to the nation, according to the Guardian.

But, inevitably, the story of how two of the three remaining Thornborough Henges, imposing 200-metre-diameter earth circles dating from the late Neolithic period, near Ripon, North Yorkshire, came into public ownership is a bit more complicated than that.

The area on which the henges are situated and most of the surrounding land has been owned by Tarmac, a subsidiary of the Anglo-American mining group, which has undertaken extensive open-cast quarrying for gravel and sand. For years, campaigners have been fighting Tarmac’s applications to extend their quarrying activities nearer the henges, which are protected ancient monuments. In 2009, the High Court quashed long-argued objections to a new quarry at Ladybridge Farm, a kilometre away from the monuments.

Then, in 2016, the Northern Echo reported that Tarmac had agreed to hand over the Thornborough Henges and 90 acres of land around them to public ownership. In return, North Yorkshire County Council’s planning committee approved the company’s application to extend its nearby Nosterfield quarry and excavate a further 2.2 million tonnes of building aggregates.

Last month’s announcement formalised the 2016 agreement. Thornborough Henges are now legally owned by Historic England as part of the National Heritage Collection. They will be managed by English Heritage and will remain free to visit, according to Historic England.

“Tarmac and Historic England have been in partnership for several years to secure the future of the Thornborough Henges, with the gifting of land always being our intention. This commitment was finally agreed as part of the planning permission granted in 2016,” says a Tarmac spokesperson. But the length of time it has taken to hand it over has mystified some.

“I don’t understand why Tarmac didn’t hand over the Thornborough land a long time ago,” says Andy Burnham, author of The Old Stones: a field guide to the megalithic sites of Britain and Ireland. “The actual area of the scheduled ancient monument is protected from development, so has never been of any use to them.”

Two million tonnes of gravel, perhaps?