After eight years of an epic battle played out across the globe, the Russian collector Dmitry Rybolovlev will have his day in court, and in no less an arena than New York. A federal judge opened the way for a jury trial for the oligarch, who claims he was swindled out of €1.2bn by the Swiss businessman Yves Bouvier in the sale of 38 works of art for €2bn between 2003 and 2014, including Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi.

But Bouvier is not a party to the litigation, which pits the Russian collector squarely against Sotheby’s. Rybolovlev, currently the owner of AS Monaco football club, accuses the auction house of having “aided and abetted Yves Bouvier in committing fraud”. He claims that Sotheby’s provided “substantial assistance” to help Bouvier overcharge on 15 works of art worth around $1bn.

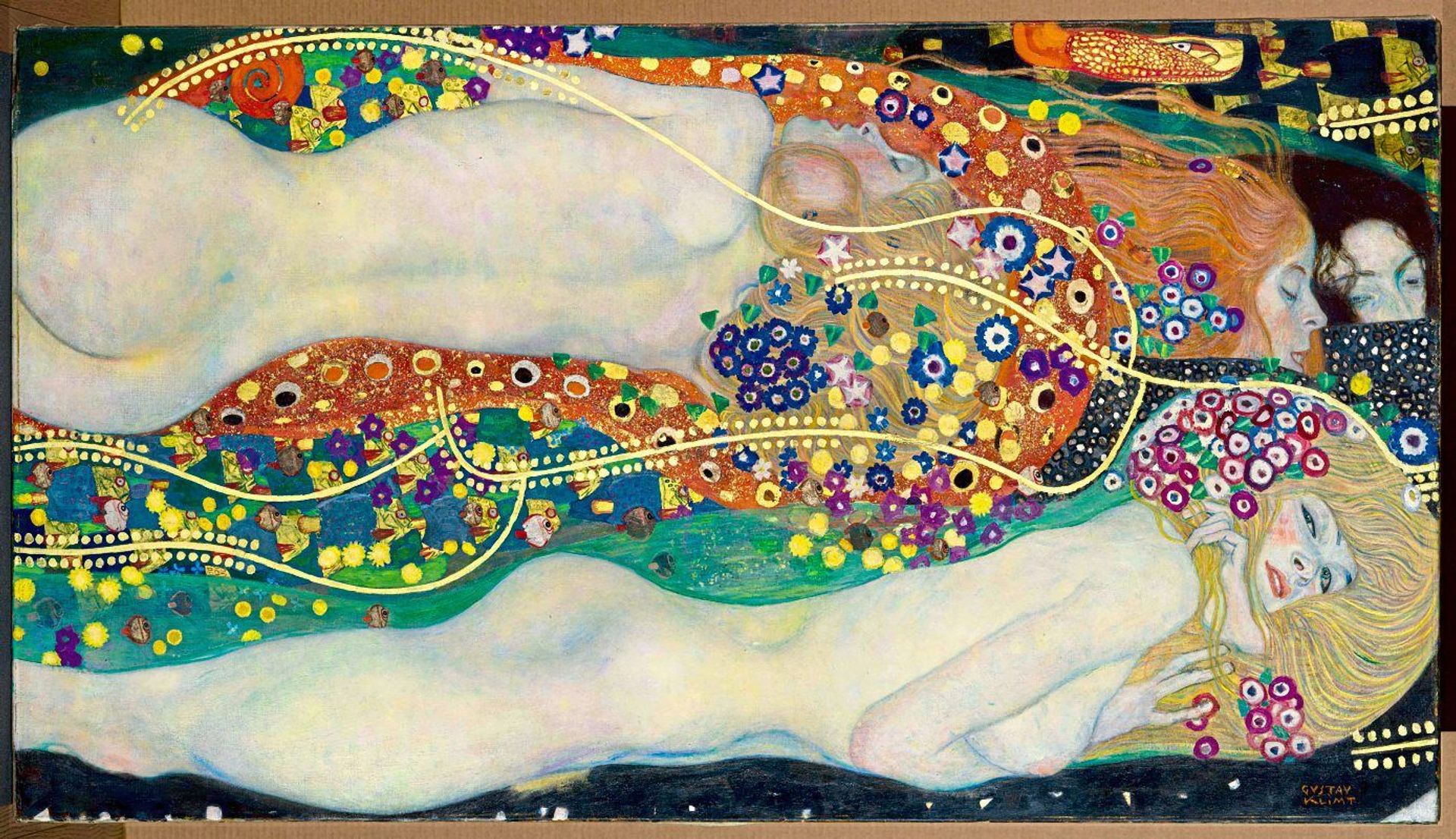

In a 76-page ruling dated 1 March, New York Southern District Judge Jesse Furman dismissed a large part of the complaint, considering that, for 11 transactions, there were not sufficient elements to conclude that Sotheby’s had knowledge of the fraud. But he concluded that Sotheby’s must face fraud-related claims on private sales made on four works: the infamous Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci (later sold at Christie’s for $450.3m), Rene Magritte’s Le Domaine d’Arnheim (1962) and Gustav Klimt’s Wasserschlangen II (1907), as well Amedeo Modigliani’s Tête (1911-12).

Gustav Klimt’s Wasserschlangen II

Dan Kornstein, the lawyer for Rybolovlev’s family trusts, says: “Judge Furman carefully analysed the facts and agreed with many of our arguments. Although not all transactions involving Sotheby’s survived the summary judgment, our remaining claims account for over $200m of damages inflicted to our clients. These are very important episodes of the case.”

In a statement, Sotheby’s says: “Sotheby’s is pleased that the court’s decision on summary judgment dismissed the majority of the plaintiffs’ claims for lack of evidence. The court also rejected the plaintiff’s own motion for summary judgment in its entirety. Sotheby’s will continue to defend this case vigorously and looks forward to prevailing on the remainder of the case at trial.”

The New York judge advised both parties to find a settlement, “without the need for a trial that would be expensive, risky, and potentially embarrassing to both sides”. However, both parties say they are now “looking forward to a jury trial”.

The ruling also draws attention to “several Sotheby’s employees” who were “involved in the art sales” in question, including Samuel Valette, a senior director and vice chairman of Sotheby’s private sales worldwide for the Impressionist and Modern art department. Valette declined to comment on the ruling.

Sotheby’s did not dispute that Rybolovlev was the victim of a fraud, an element that the judge considered as “supported by the record”. But the company denied in court having “any knowledge of the fraud” and claimed it “did nothing to facilitate Bouvier’s business”.

The document details how Bouvier made huge profits on works he purchased through Sotheby’s. It also gives an idea of the extent of their privileged relationship: from 2005 to 2015, Sotheby’s registered more than 800 transactions with the Swiss dealer.

Bouvier tells The Art Newspaper that, not being a litigator, he was “observing the New York lawsuit from afar”. He says he met Valette through the Corsican Jean-Marc Peretti, a common friend. Peretti, a former manager of gambling rings, opened an art gallery in Geneva Freeport in 2008. “He was not a partner,” Bouvier says, “but someone who just helped me on three occasions to negotiate with Valette, on a friendly basis”.

The first deal was brokered in 2011, when Valette sent descriptions of a Picasso painting to both men. The day it was consigned to Sotheby’s in Geneva, Bouvier emailed Rybolovlev’s representative, Mikhail Sazonov, to say that he was in contact with the seller who had asked for $150m, but was prepared to go down to $107.5m. “But these negotiations never happened”, says the judge. The day Bouvier purchased the painting from Sotheby’s, for $62m, he sent an invoice of $107.5m to Rybolovlev, pocketing $45.5m in the space of a few hours.

Bouvier told The Art Newspaper that he "regularly invented negotiations with a seller”, but that this is a usual tactic for dealers and in no way a criminal offence.

Bouvier has always denied any wrongdoing, claiming he acted as a dealer, free to set his own profit margins, and not as an agent. The judge acknowledged that the first contracts signed between Rybolovlev and Bouvier “did not mention any agency relationship” and the Swiss businessman “did not consistently invoice...for a commission, as would be typical for an agent”.

For Rodin’s marble L’éternel printemps, Bouvier more than doubled the price, from $13.2m to £30m. Sometimes, the work was even sold to Rybolovlev before being purchased from Sotheby’s. Such was the case, in 2011, with a version of Le domaine d’Arnheim by Magritte, for which Bouvier invoiced Rybolovlev $43.5m, three days before executing a purchase agreement with Valette, for $20m less. Although he claims he was never aware of Bouvier’s deals, according to the judge’s ruling, in February 2011 Valette emailed some of Sotheby’s employees that Peretti’s “Russian client is in New York next week and is looking for large colourful works”.

In the case of the Salvator Mundi, before the sale, Valette presented the painting to Rybolovlev at his penthouse on Central Park West—at the time the most valuable apartment in Manhattan. Valette claims he had no idea who the owner was. But this did not convince the judge, who maintained that Rybolovlev “provided evidence that Sotheby’s knew Bouvier purchased the Salvator Mundi...[on his behalf]...and that Valette worked closely with Bouvier to adjust its valuation”. Bouvier bought the work for $83m before selling it to Rybolovlev for $127.5m. When the dealers who had consigned the Leonardo painting to Sotheby’s learnt this in the media, they claimed they had been deprived of a $50m benefit, and Sotheby’s had to settle out of court.

According to the ruling, “Sotheby’s executives’ heavy involvement in the negotiations, combined with the viewing that Valette co-ordinated, are sufficient evidence of Sotheby’s substantial assistance to Bouvier” for this sale.

Valette also “coordinated a viewing of the Klimt where he saw Rybolovlev”, two weeks before the sale. In the case of Modigliani’s Tête, “two years after Sotheby’s estimated the fair market value of the sculpture to be €8m, and a month after the seller consigned it to Sotheby’s for €55m, Valette sent Bouvier a formal email, estimating the value at €70m to €90m. Less than twelve hours later, Valette sent Bouvier an almost identical email, this time valuing the sculpture at €80m-€100m. From this evidence, a jury could certainly infer that…Valette raised his estimate at Bouvier’s request. Put differently, Valette provided Bouvier with materials inflating the price of the sculpture — circumstantial evidence of Valette’s knowledge of Bouvier’s scheme.”

In his estimates for value insurance, after the sales, Valette regularly raised the draft valuation submitted to Bouvier. But he also skipped any record of his purchases in the provenance. When, in 2014, Bouvier bought back Modigliani’s Tête and put it up at auction, Sotheby’s also “intentionally omitted mention” of his company in the provenance listed in the catalogue, making a “substantial contribution to Bouvier’s frauds”, according to the ruling. “Maybe better to cover the tracks slightly and designate as: Property from a Private European Collection,” Valette said in an email to an employee.

According to the judge’s ruling: “Beginning with the sale of Magritte’s Le Domaine d’Arnheim (in December 2011) and Modigliani’s Tête (in January 2013), the record suggests that Valette adjusted his estimated valuations of these two works to suit Bouvier, before Bouvier sold the works to Plaintiffs … Plaintiffs have thus presented evidence that Valette was aware of Bouvier’s price manipulation, the essence of his scheme.”

UPDATE: Sotheby's confirmed after publication that the auction house and the plaintiffs "have accepted the court’s recommendation to engage in settlement talks, and have agreed to proceed by mediation with a magistrate judge." If the case is not resolved a mediation, it will proceed to trial