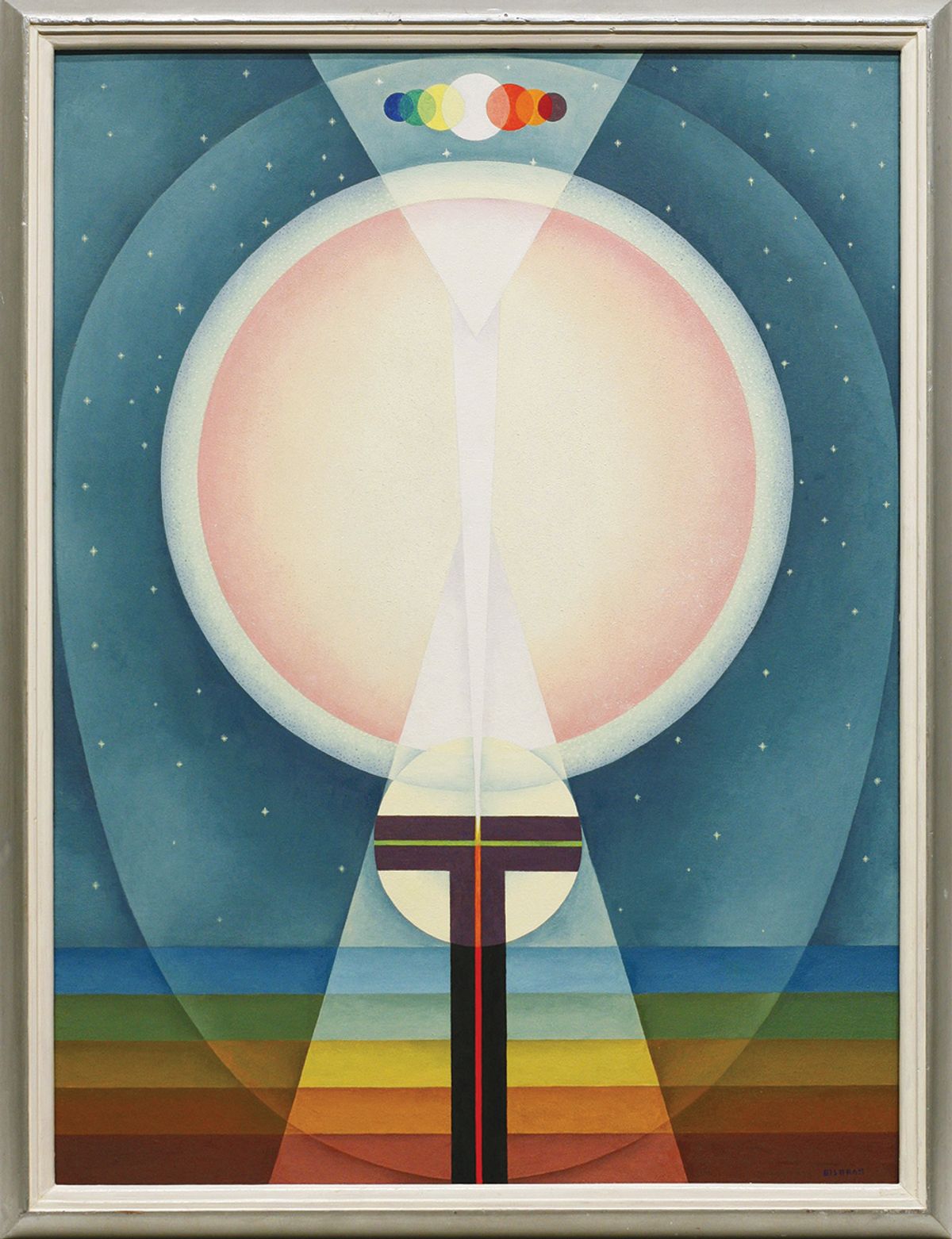

Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group, 1938-1945

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, until 19 June

In tandem with the recent rise of painters who find transcendence in abstractions of the body and landscape—think Loie Hollowell and Shara Hughes—has come a growing appreciation of their precursors, Modernists who gave form to the spirit and who had long been left out of dominant histories of art. Foremost among them is the short-lived but enduringly influential Transcendental Painting Group, which flourished in Taos and Santa Fe, New Mexico and defined itself in opposition to the prevailing rationalism and rigid geometries of the day.

The group, which came to include Agnes Pelton, Lawren Harris, Florence Miller Pierce, Horace Pierce, William Lumpkins and Dane Rudhyar, among others, followed the guidance of Raymond Jonson and Emil Bisttram, who were in turn heavily influenced by the colour theories of Wassily Kandinsky. In the group’s 1938 manifesto, they wrote that “spiritual values are just as proper working material as the objective or physical” and maintained that “our spiritual self is just as definite a fact as our physical self, in fact the combination of both is necessary for life’s fulfilment”.

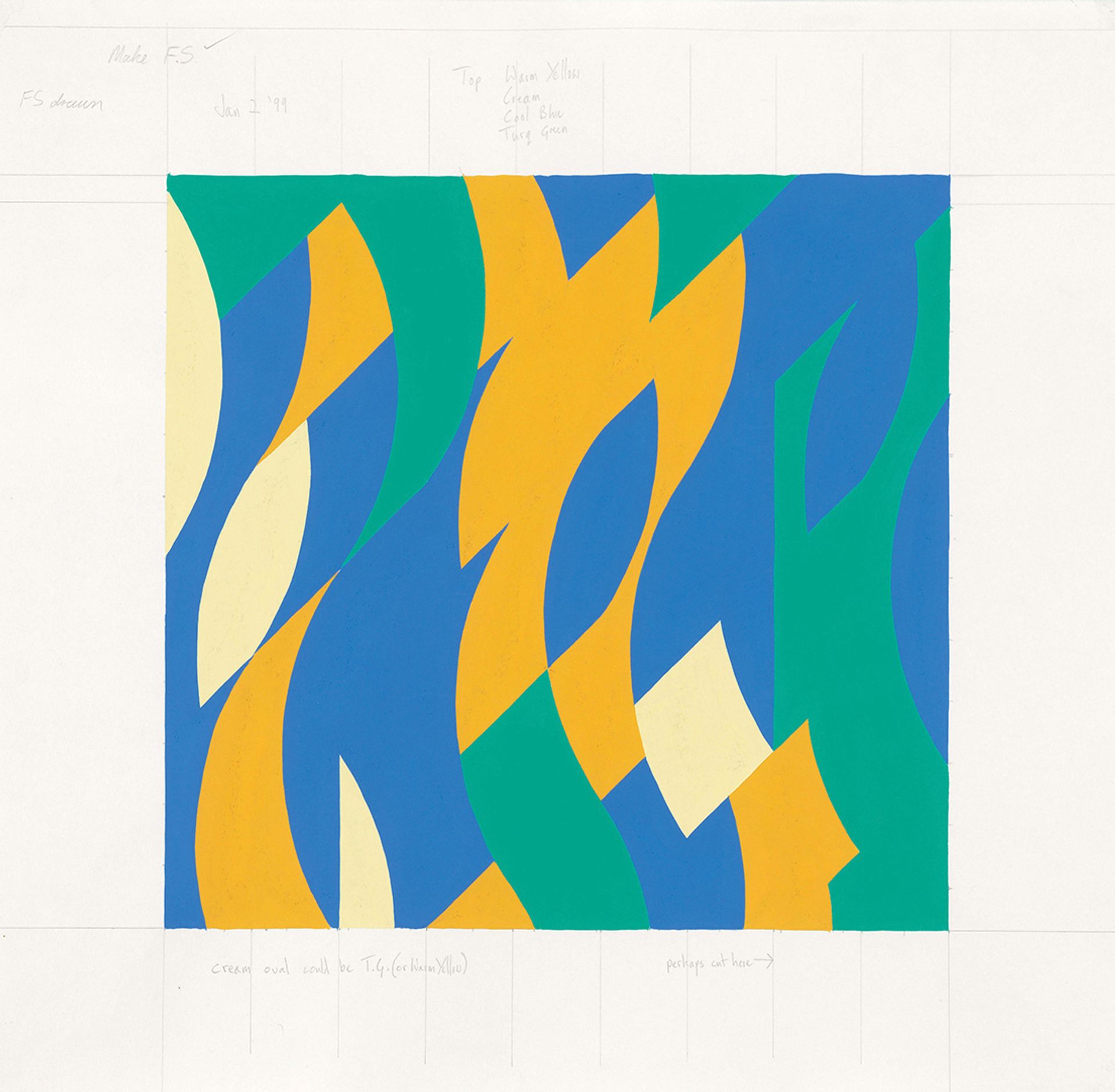

Bridget Riley’s New Curves—January 2 ’99 (1999), a preliminary work on paper in pencil and gouache Collection of the artist, © Bridget Riley

Bridget Riley Drawings: From the Artist’s Studio

Hammer Museum, until 28 May

Drawing, for the artist Bridget Riley, is an act of discovery, a way to learn by doing and work through problems. The process is “an enquiry, a way of finding out—the first thing that I discover is that I do not know”, she wrote in her essay “Work” (2009). “It is as though there is an eye at the end of my pencil, which tries, independently of my personal general-purpose eye, to penetrate a kind of obscuring veil or thickness.”

Riley’s drawings have rarely been exhibited en masse but, together, they provide invaluable insight into her changing approach to line and colour, as the travelling show Bridget Riley Drawings: From the Artist’s Studio reveals. The exhibition brings together more than 90 works on paper selected from Riley’s London studios, many never before seen. A retrospective of sorts, it is arranged chronologically, with early works shown in a central room nested within the main gallery. Among these are richly toned landscape and Conté crayon studies from life-drawing classes at Goldsmiths’ College, where she studied from 1949 to 1952. Drawing taught her how to look and to understand the potential of tone, leading to the illusive gradations she continues to explore.

In making her show, Helen Cammock explored the resources of the Amistad Research Center, an archive of African American history © Helen Cammock 2022

Helen Cammock: I Will Keep My Soul

Art + Practice, until 5 August

Helen Cammock is attentive to who and what is rendered in the historical record, and the gaps between. Her videos, screenprints, writings and installations bridge and collapse time and geographies, and have focused on groups including Black migrants to Europe and women involved in the 1960s civil rights movement in Northern Ireland. Her exhibition at Art + Practice, I Will Keep My Soul, weaves contemporary lives from New Orleans’s creative community with historical threads pertaining to this rich but undervalued enclave.

Organised by the California African American Museum and the Rivers Institute for Contemporary Art and Thought, the exhibition is Cammock’s first in the US. It stems from a residency at the Rivers Institute that invites artists to engage with the Amistad Research Center in New Orleans, the nation’s oldest and largest independent archive specialising in African American history. Bringing archival material into an open, present-day dialogue, I Will Keep My Soul is a convening of perspectives and politics, and an invitation to consider one’s own agency within shared struggles.

A Civil War Zouave quilt (mid- to late-1860s) from the Museum of Fine Arts Boston is included in the Skirball Cultural Center show © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories

Skirball Cultural Center, until 12 March

Examining the historical function of quilts and their rich formal evolution—from unique takes on abstraction to elaborate, narrative compositions—this exhibition brings together examples spanning some 300 years. It includes intricate pictorial quilts by Harriet Powers, a formerly enslaved woman active in rural Georgia in the late 19th century. Also on view are quilts made in response to specific historical events such as the US Civil War, the women’s suffrage movement and, in a colourful retrofuturist cityscape by Richard H. Rowley from 1933, the centennial of Chicago. The show juxtaposes these and other rare examples with recent quilt-based works by contemporary artists such as Sanford Biggers, Bisa Butler, Faith Ringgold, Carla Hemlock and many others intent on building on the medium’s history.

Twilight (2021) by Carmen Mardonez, who explores the problematic nature of craft and feminity

Courtesy of the artist

Strings of Desire

Craft Contemporary, until 7 May

This exhibition gathers many strands of contemporary embroidery, a thread running through the work of the 13 featured artists showing a desire to convey identity and connectivity via their practices. For many of the participants, embroidery is a material and symbolic expression of experiences that are multifaceted or hybrid. With Ken Gun Min, for instance, his Korean heritage, experiences of coming of age in Europe and the US, queer identity and an omnivorous visual lexicon result in rich tapestries that combine fabric patterns, anatomical drawings, animals, landscapes and hybrid figures.

For many of the featured artists, embroidery is not only a symbol of connection but also a vessel for it. In the case of Ardeshir Tabrizi and Jordan Nasser, traditional textile crafts link them to their Persian and Palestinian heritage, respectively. The Los Angeles-based artist Miguel Osuna does much of his embroidery during Zoom calls with his mother, who lives in Mexico, the shared activity allowing them to connect and share tactile experiences across great distances.

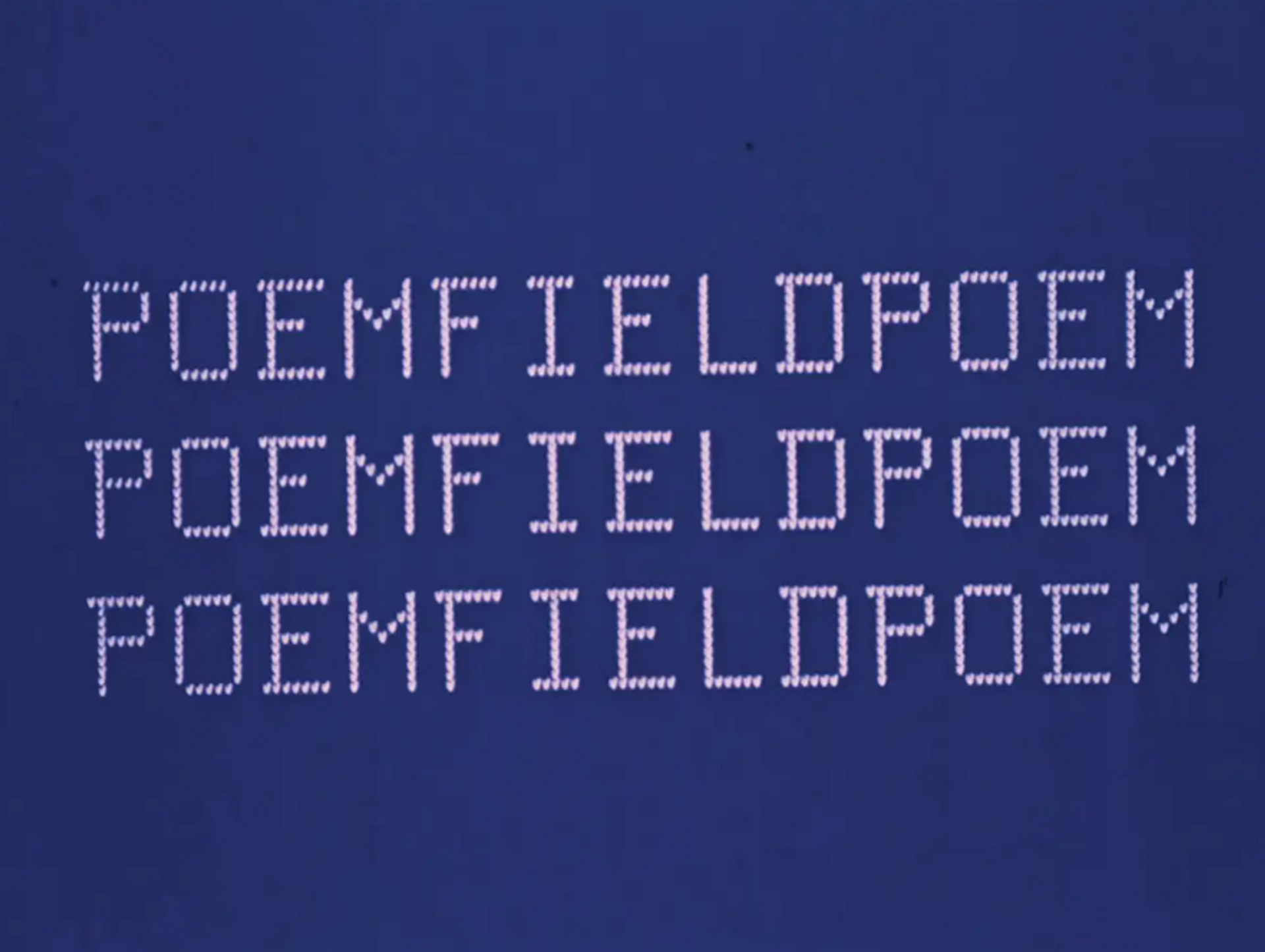

Poemfield No. 1 (Blue Version), a 1967 animation created by the filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek and the physicist Kenneth Knowlton

© Estate of Stan VanDerBeek

Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952-1982

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, until 2 July

As the parallel fields of artificial intelligence and NFTs (non-fungible tokens) continue to dominate art-world discourse in 2023, it is tempting to conceive of the relationship between art and technology as a project of futurity alone, defined by the kind of rampant obsolescence we associate with market trends and media cycles. Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952-1982 upends that presumption as it examines the rise of creative production in the age of the mainframe, drawing urgent throughlines between emergent coding systems and digital art as we understand it today. Featuring more than 100 objects made by 75 artists, the show’s chronological point of origin is 1952, the year the first entirely aesthetic image was rendered by computer, and ends in 1982, when the personal computer usurped the mainframe as the technological power du jour.

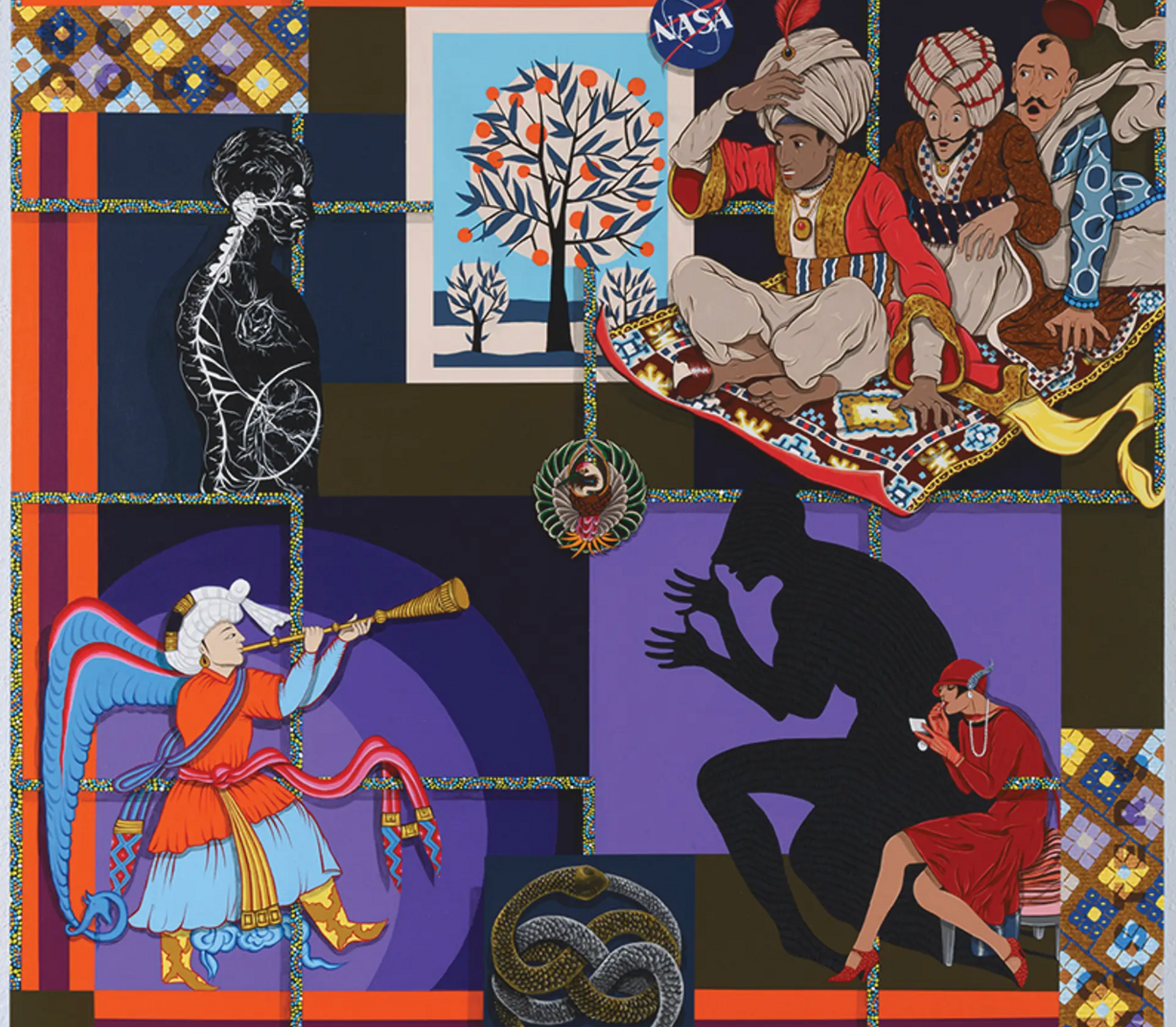

Amir H. Fallah’s No Gods No Masters (2020), which features in the Fowler Museum’s show; the Tehran-born artist draws on the diasporic Iranian American experience

Courtesy of Shulamit Nazarian

Amir H. Fallah: The Fallacy of Borders

Fowler Museum, until 14 May

Los-Angeles based artist Amir H. Fallah has always taken the “more-is-more” approach to painting. “I really just try to cram everything in there that I can,” he says. It stands to reason, then, that his first institutional solo exhibition in the city feels like a love letter to maximalism itself, a meditation on the electric noise of an increasingly interconnected age. Born in Tehran at the height of the Islamic Revolution, Fallah mines the diasporic Iranian American experience through the spirit of remix, drawing on traditions as disparate as 17th-century Flemish still-lifes and graffiti to achieve a vibrant depth of meaning in his work. According to curator Amy Landau, the director of interpretation and education at the Fowler Museum, Fallah “narrates from trauma and celebration, as well as his roles as a husband, father and confidant, which lends a deeply humane aspect to his social critique”.

Yara Training Bag (around 1990) and Three Monitors with Yara Videos (around 1980s and 1990s) explore the African dance-inspired martial art invented by Milford Graves

Filip Wolak

Milford Graves: Fundamental Frequency

Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, until 14 May

This celebration of the revered Renaissance man and polymath Milford Graves (1941-2021) attempts to bring together as many facets of his life and work as possible. A pioneer of the Free Jazz movement, the New York-born percussionist studied to be a cardiac technician so that he could learn about the heartbeat and its connection to rhythm. He also invented the martial art Yara, which was inspired by eclectic sources including African dance and the movements of the praying mantis.

On view are videos and other documentation of Graves’s performances, intricate assemblage sculptures, decorated instruments, costumes, hand-painted album covers and so much more. What emerges from these varied materials is a holistic approach that informed everything Graves created. “When I come to my instrument, I am relaxed and can pull stuff off,” the artist said in a 2018 interview with BOMB magazine. “When I was doing tai chi, I would bring that fluidity in. It’s not just about practice; there are a lot of other experiences to have. In acupuncture, I can hit some dangerous points—bam! That’s drumming.”