Researchers have discovered more than 50 coded letters written by Mary Stuart, better known as Mary Queen of Scots. Stored among a collection of enciphered documents in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, they were composed between 1578 and 1584, while Mary was imprisoned by her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I.

“This is the most significant discovery of letters from Mary Stuart in recent years,” say George Lasry, Norbert Biermann, and Satoshi Tomokiyo, the research team that cracked the code.

The decoded letters, published in the journal Cryptologia, mention Mary’s poor health, negotiations for her release, the abduction of her son (the future King James I), and her conditions in captivity. Mary also discusses the schemes of Elizabeth’s spymaster Francis Walsingham, and her hostility towards the Earl of Leicester Robert Dudley, as well as plots, the recruitment of spies, and attempts to bribe officials.

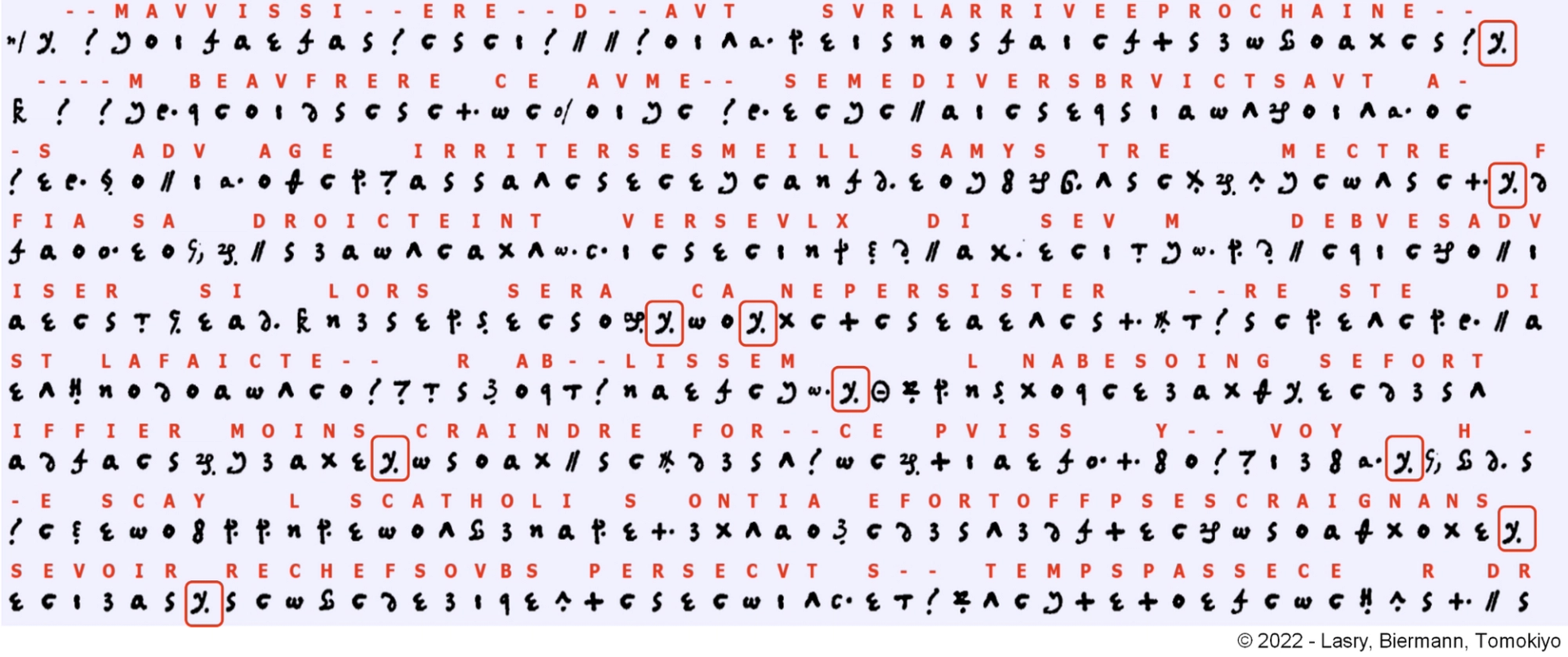

The cipher symbols and decryptions of one of the letters

© Lasry, Biermann, Tomokiyo

Written in French, most of the correspondence was addressed to Michel de Castelnau, France’s ambassador in London, who was a supporter of Mary and passed on her messages to allies. The letters’ dates reveal that this secret channel was in use by May 1578, earlier than historians previously thought.

The researchers discovered the correspondence while searching through the French library’s online archive. Initially, they didn’t suspect Mary to be the author, not only because the letters were written in code, but because the library’s records associated them with Italy.

“The code is quite elaborate, and it took us a while to crack it,” the researchers say. “But after a while, we started to see some plausible fragments of text in French. From those fragments, it emerged that the writer was in captivity, had a son, and was a woman, which could match Mary Stuart.”

Using a combination of computerised and manual codebreaking techniques, the researchers found that multiple symbols could represent a single letter or syllable, and that others represented names, places, and months. They also noticed errors in the code, which were probably the result of Mary using multiple encoding systems, selected depending on the recipient.

“The definitive clue was the mention of Francis Walsingham, Queen Elizabeth’s first secretary and spymaster, who is well known for having spied on Mary during her captivity,” the researchers say.

In total, historians now have around 50,000 words of new information on Mary’s life to analyse. “There are 57 encoded letters which we deciphered,” the researchers say. “We were able to locate copies of a few of them in British archives, but the remaining 50 or so are unpublished and previously unknown to historians.”