After clambering up a precarious ladder, I pulled myself up into an attic in Ealing, West London, where a great-granddaughter of Harry Gladwell was helping me search for family memorabilia. Gladwell became a friend of Van Gogh in 1875, when they were both trainee art dealers in Paris, and I had wondered whether anything might survive from their few months living together. The men were close, and Van Gogh would call Gladwell “my worthy Englishman”.

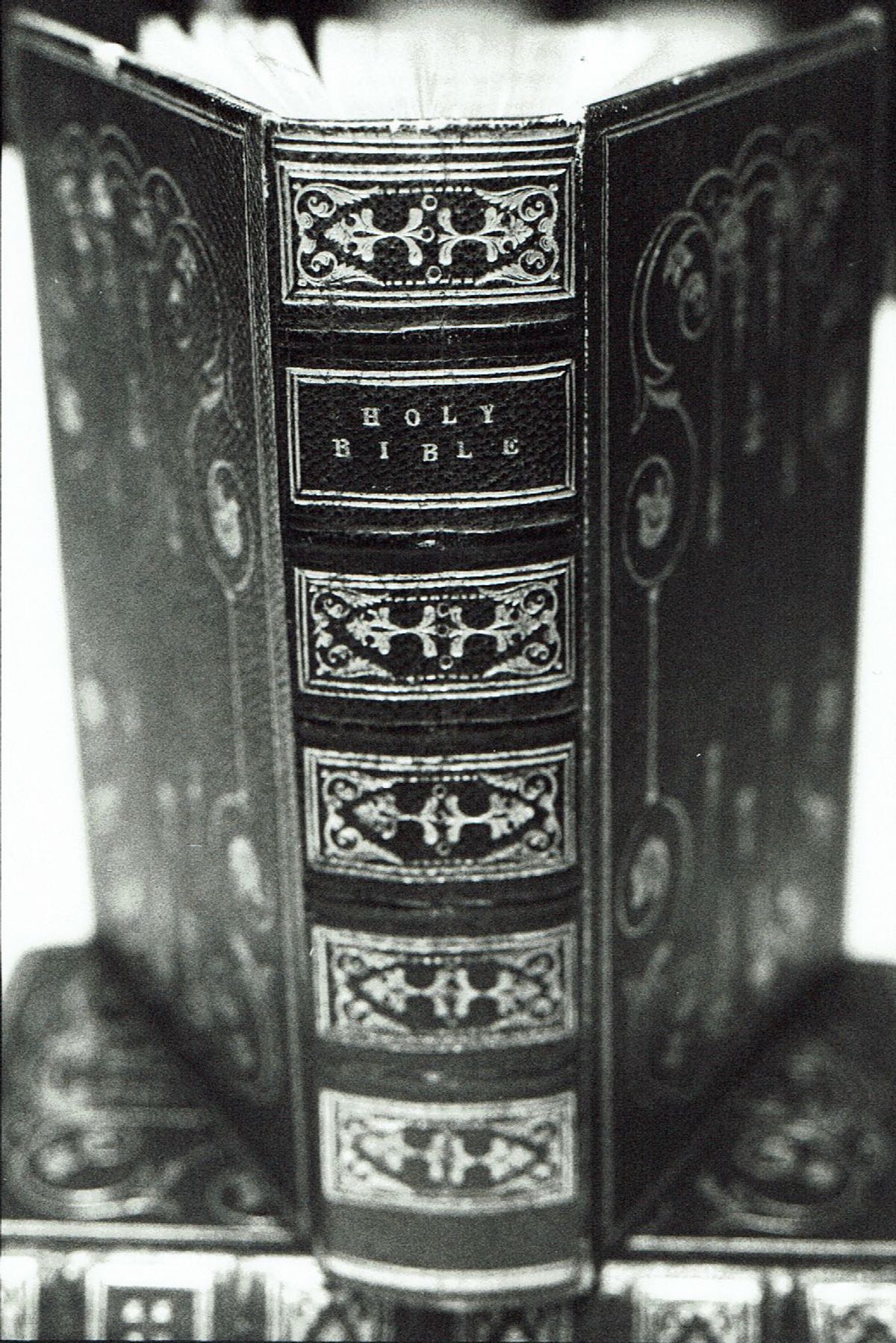

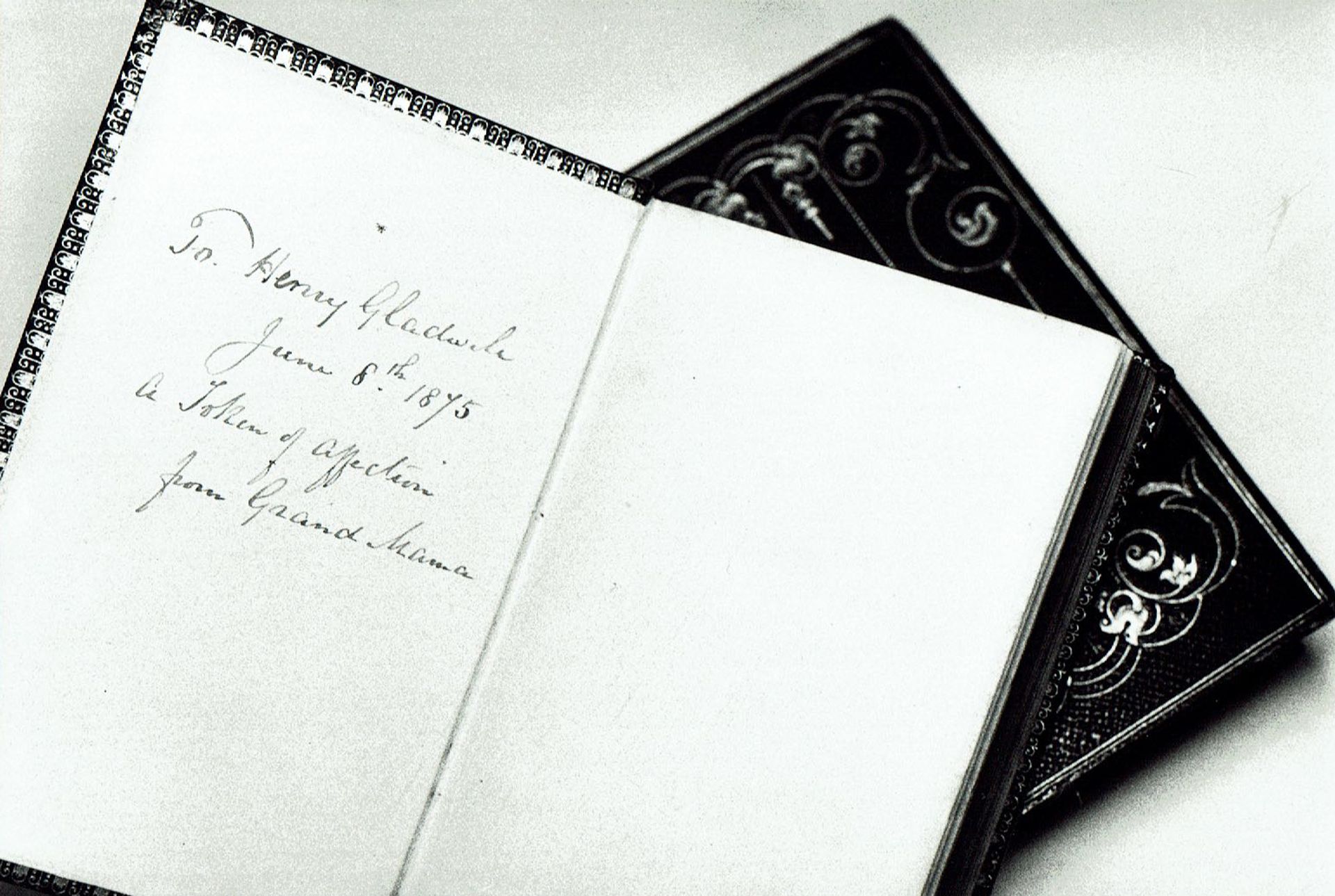

With mounting excitement, we opened a trunk and found a framed photograph of the young Gladwell and two leather-bound volumes, a Bible and The Book of Common Prayer. To my delight, the books contained a dedication: “A token of affection from Grand Mama.” I also noticed a pencilled English text just before the Bible’s title page, which I later identified as a verse from the Gospel of John.

Harry Gladwell’s Bible, dedicated on 8 June 1875 Credit: private collection

To my astonishment, the grandmother’s dedication also included the date 8 June 1875, which was precisely the period I was looking for. Van Gogh had moved to Paris in May that year and soon afterwards he would share a tiny apartment in Montmartre with Gladwell. Amazingly, the two books had survived in the Gladwell family for well over a century.

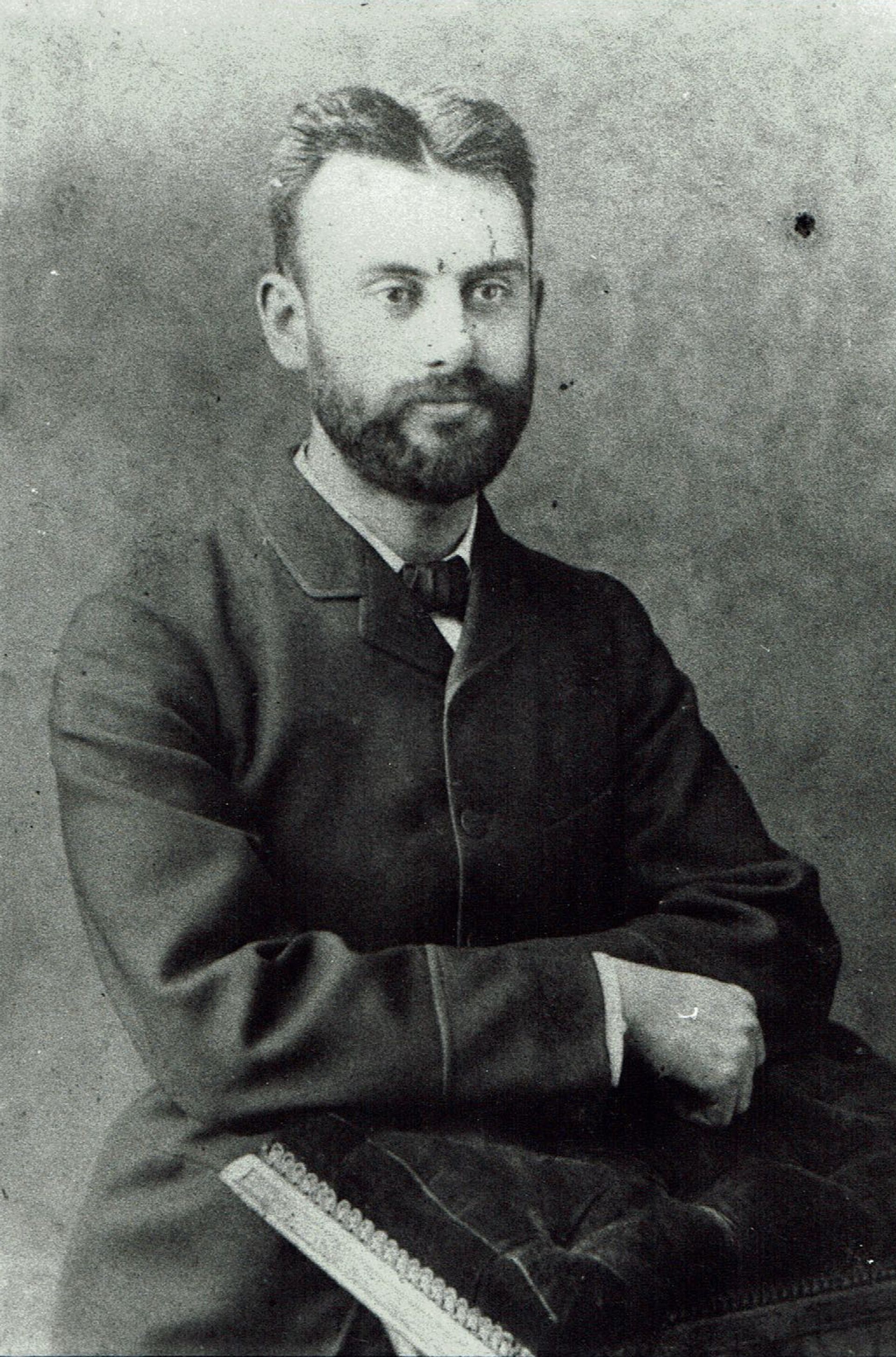

Photograph of Henry (Harry) William Gladwell (1857-1927), in his twenties (1880s), a few years after lodging with Van Gogh Credit: private collection

Vincent, then aged 22, wrote about his new friend in a letter to his brother Theo: “I live in Montmartre. Also living here is a young Englishman, an employee of the firm, 18 years old, the son of an art dealer in London… I’m very glad of his company in the evenings. He has a completely naive and unspoiled heart, and works very hard.” The two young men were both trainees at the Paris-based Goupil art gallery.

The letter then added a key detail: “Every evening we go home together, eat something or other in my room, and the rest of the evening I read aloud, usually from the Bible. We intend to read it all the way through.” Reading aloud the whole Bible would take around 80 hours in total.

After descending the ladder, the generous great-granddaughter allowed me to borrow the Bible and The Book of Common Prayer for an exhibition on Van Gogh in England which I curated at the Barbican Art Gallery in 1992. The Van Gogh Museum’s specialist, Louis van Tilborgh, later visited the show—and confirmed the exciting discovery that the handwriting of the Biblical verse is actually that of Van Gogh.

The text is from John, chapter 17, verse 15, written out by Van Gogh as: “Father we do not pray thee to take us out of the world, but we pray thee to keep us from evil.” As so often when writing out texts, he made a few minor mistakes in his transcription.

This verse from John was one of Van Gogh’s most cherished Biblical sayings, at a time when he was highly religious. He quoted it in no fewer than 11 letters to his family.

The pair of books are small, just five inches high, making them ideal for a traveller and they were presented to Gladwell just before leaving home for the first time. Presumably his grandmother was concerned about his trip abroad—and to Paris, then renowned for its boisterous artistic nightlife in Montmartre. Although this is speculation, she may have felt that reading the Bible would encourage the young man to keep to the straight and narrow.

We are on firmer ground in knowing why Vincent attached so much importance to John 17:15. Anna, his mother, had recited this verse when he too had left home. A few months after his period in Paris he recalled that this was “the prayer my Mother said for me when I left my parents’ house”.

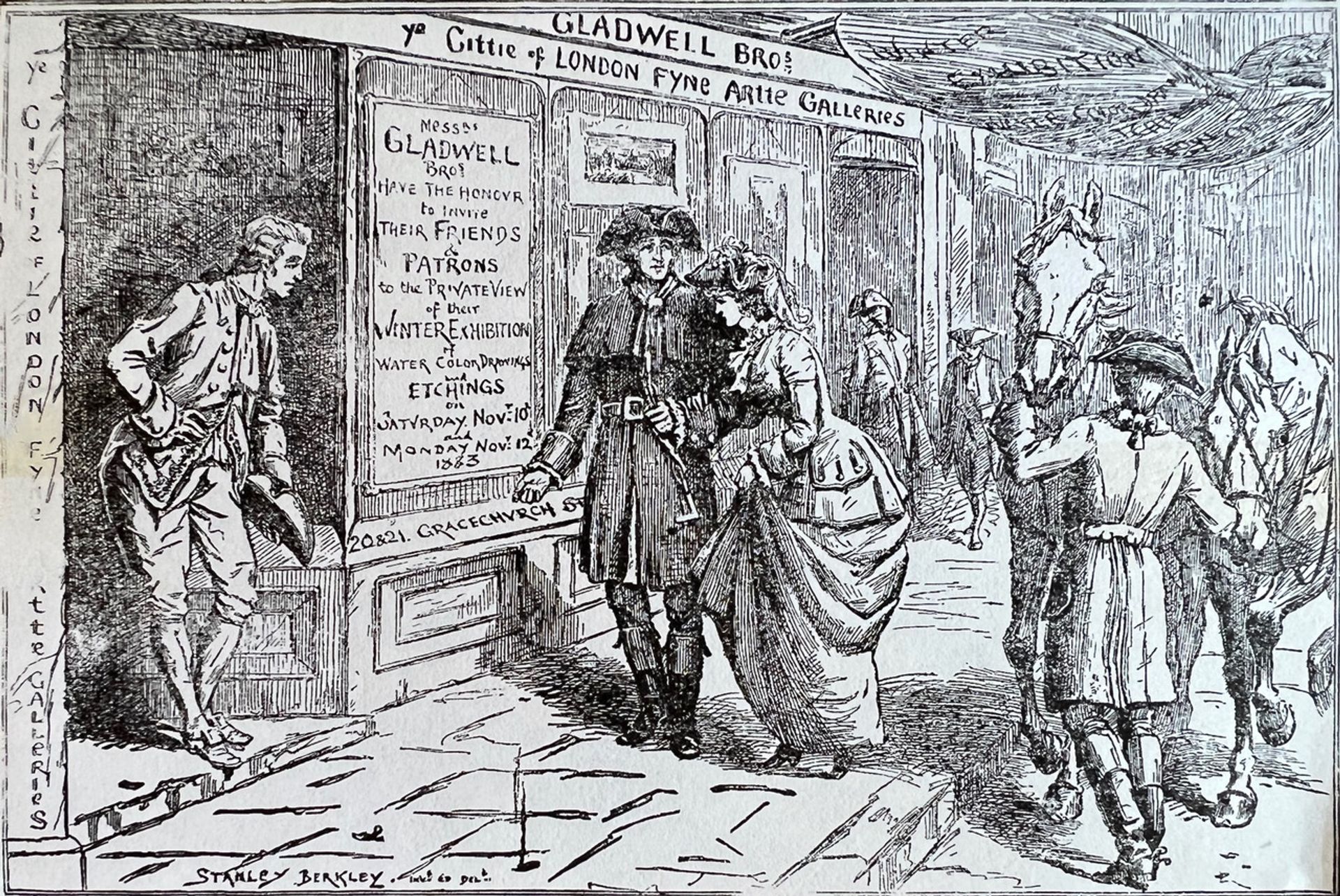

Thomas Dibden’s watercolour The Gladwell Gallery (1882), then located at 20-21 Gracechurch St, London Credit: Guildhall Library, London Photo: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

The Gladwell gallery in London, which Harry later took over from his father, still survives and is regarded as the oldest art dealer in London, with its origins dating back to 1746. It is now known as Gladwell & Patterson, after W.H. Patterson’s gallery was taken over in 2004, and is now located at 5 Beauchamp Place, London SW3 1NG.

The gallery currently has an intriguing small display of memorabilia from its long history, entitled Looking Forward to the Past. It has been extended, for the benefit of readers of The Art Newspaper, but do go quickly, since it closes on 9 February. The gallery has also just published an illustrated history of the same name edited by the gallery owner Glenn Fuller.

During their time in Paris together, Van Gogh encouraged Gladwell to abandon his career as an art dealer and to become a preacher. As Vincent explained to Theo in March 1878, “I still have hopes of his becoming a minister, and if that happens he’ll do it well”. In fact, this is what Van Gogh himself set out to do a few months later. In December 1878 he left for the Borinage, a poverty-stricken coal mining area in Belgium, where he preached to the miners. As for Gladwell, he soon became a successful London art dealer. He died in 1927, aged 70.

A private view invitation card designed by Stanley Berkley for a Gladwell Brothers exhibition (November 1883), and currently on display at Gladwell & Patterson, 5 Beauchamp Place, London SW3 1NG Credit: Gladwell & Patterson, London

Gladwell and Van Gogh corresponded for several years after their time in Paris and Vincent’s unpublished letters are believed to have survived until the Second World War. They were then lost, probably when the gallery was bombed during the Blitz in 1940-41.

As for the Bible and The Book of Common Prayer, they were returned to the Gladwells after the Barbican exhibition. Their owner went abroad, and I then lost contact with the family. Thirty years on, one hopes that the pair of books survive and their link with Van Gogh is still treasured.

The two volumes represent both a testimony to Van Gogh’s deep commitment to Christianity in his early 20s and the important friendship with his “worthy Englishman”.

• Looking Forward to the Past, Gladwell & Patterson, London, until 9 February

Other Van Gogh news:

Installation view of Klimt: Inspired by Van Gogh, Rodin, Matisse (including, in the centre, Van Gogh’s Orchard in Blossom, April 1889) at the Belvedere, Vienna Credit: Johannes Stoll/Belvedere, Vienna

The exhibition Klimt: Inspired by Van Gogh, Rodin, Matisse opens today (3 February) at the Belvedere in Vienna and runs until 29 May.