"These are people I love. They are homages," says Adam McEwen, the New York-based, London-born artist about a new group of hypothetical obituary articles of living celebrities that he has created for his first one-man show in London.

McEwen's much-enlarged facsimiles of newspaper obituaries address the imagined loss of seven living subjects: the publicity-shy artist David Hammons; the tech pioneer and prophet Jaron Lanier, the climate activist Greta Thunberg, the spiritual leader and mystic Sadhguru and the singers Dolly Parton, Grace Jones and Marc Almond.

"I think of the people I choose to do," McEwen tells The Art Newspaper, "as models, in a sense, or guides [to life]." He says he sees the collective message of his subjects—all of them decision-makers and mould-breakers—as essentially optimistic.

Rule-changers: Adam McEwen's hypothetical obituaries of Greta Thunberg, Sadhguru, Dolly Parton and David Hammons at Gagosian, Davies Street, London © Adam McEwen. Photo: Lucy Dawkins. Courtesy Gagosian

McEwen has made these works—60in tall and dry mounted for the show at Gagosian, Davies Street—so that they can be viewed, and read, like posters, by two or three people at a time. In their chaste graphic presentation—with black and white photographs centrally placed under functional headlines and scanned to resemble the gritty 200 dots-per-inch resolution used for printing on newspaper presses—the works are anchored in the visual world of the mid-1990s when McEwen, a recent graduate of California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) looking to fund his life as an artist, worked as an obituary writer at The Daily Telegraph in London.

McEwen's pieces play with the fact that an obituary article is not about death per se but is an informed, though not uncritical, profile of personal achievement; the first draft of biography; an analysis of the change wrought by time on personal reputation; an article that might answer Carl Jung's injunction that "the beloved dead are our task". McEwen sees his conceptual obituaries, in the way they memorialise their subjects' decision-making, as "optimistic in the face of oblivion": as if he had made "the beloved living" his task.

Life as an obituary writer

McEwen wrote at The Daily Telegraph at a time when quality newspapers in London regarded their obituaries pages—which had been stirred up by the entry into the market of The Independent in 1986—as high-profile arenas of editorial competition; in a battle to be the market-leader and the newspaper of record for the recently deceased.

The Daily Telegraph and The Times stuck to a historic practice of publishing unsigned obituary articles, aspiring to an anonymous, detached-seeming objectivity. The Guardian followed The Independent's practice (also adopted by The Art Newspaper after its launch in 1990) of running signed articles, where the author's identity is part of the editorial transparency with which the subject's achievements are assessed, while explaining the context of their working lives, and where the judicious use of the first person may be usefully deployed.

The language, as much as the typographical design, of McEwen's pieces is a testament to The Daily Telegraph of the 1990s, where McEwen's boss was the celebrated Hugh Massingberd (1946-2007), a characterful historian and genealogist who had devised a laconic, nudging, coded prose for the Telegraph obituaries page. "There was a dry, understated, style," McEwen says, "which ... was a very clever way to imply things ... [while] trying to be factual."

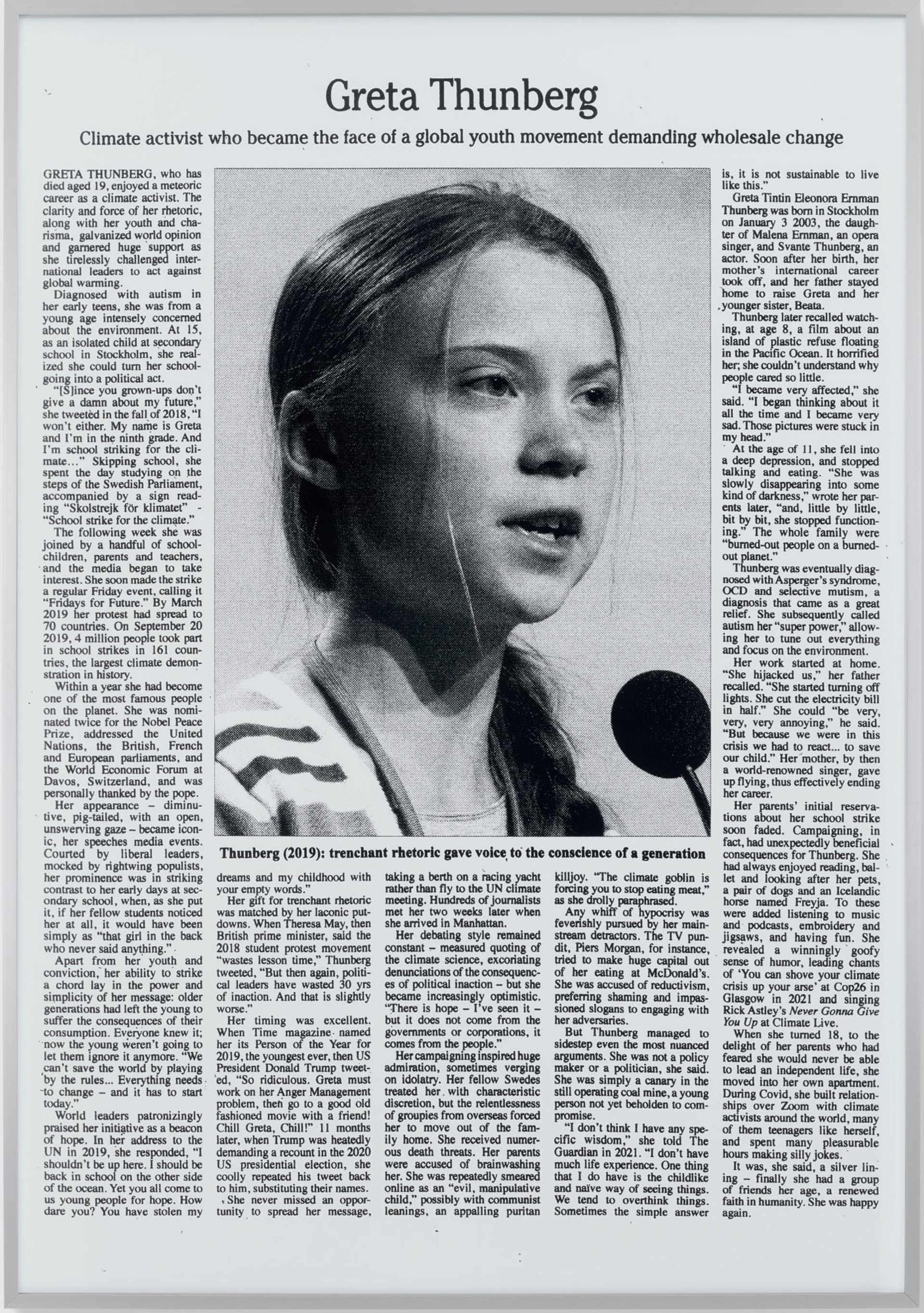

"These guides are rule-changers": Adam McEwen, Untitled (Greta) (2023) © Adam McEwen. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Courtesy Gagosian

When McEwen was asked to write an obituary in advance (to be kept on file by The Daily Telegraph) or in response to the news—he wrote an article on John F. Kennedy Junior when the light aeroplane Kennedy was piloting went missing on his way from New York to Martha's Vineyard on 16 July 1999—he sometimes wondered to himself at the challenge of writing instant history when he had no personal knowledge; where everything he produced was dependent on trusting published sources, from newspaper cuttings to the nascent internet. That challenge was an early case for McEwen of creating certainty on uncertain foundations. In succeeding decades he has demonstrated an interest in his art in the uncannily real, in material decay and sell-by dates, and the shifting of life's foundations; where the only certainty is the finiteness of life.

A hypothetical Malcolm McLaren

McEwen's first exercise in hypothetical obituary was a piece on Malcolm McLaren, the godfather of Punk, which he devised using the fonts and design of The Daily Telegraph. It was shown in a group exhibition in London, organised by the gallerist Paul Stolper, where "everyone was given a muslin Vivienne Westwood shirt". Not long after, in 2000, McEwen, then 35, gave up his life as an obituarist and moved to New York City to make a fresh start as an artist.

Work on a documentary about the band Sly and the Family Stone tided McEwen over during his early days in the Big Apple. Resisting offers of further well-paid television projects, he started a series of works inspired by another genre of understated messaging, very different to that of The Daily Telegraph—the "Sorry" signs on sale in New York hardware shops that read "Sorry, we're closed". "'Sorry, we’re sorry,' 'Sorry, we’re dead'," McEwen says, musing on that series. "They were really about not being able to make art." But he exhibited his "Sorry" pieces in group shows and, from there, things "slowly snowballed".

At the same time, the concept obituaries, represented by the McLaren piece, were "asking to be made". "The next one I did was Rod Stewart," McEwen says, "and [then] Bill Clinton and Nicole Kidman." These were shown in a group of seven such pieces in 2004. In 2011, McEwen added the novelist Bret Easton Ellis, the Burmese politician Aung San Suu Kyi and Princess Stephanie of Monaco to the group. There were no “lies” in the pieces, McEwen says, nothing invented, except the standard wording "who has died, aged...". "It was only in the selection of the pieces that my bias was evident," he says. "These are people I love."

In 2020-21, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, included McEwen's Kidman piece, Untitled (Nicole) (2004) from its collection, in its Pictures, Revisited survey of artists who have worked with image appropriation. McEwen added to his roster of hypothetical obituaries in his April 2022 show Execute—at Gagosian, 980 Madison Avenue, New York City—with pieces on three of the subjects of his London show: Sadhguru, Lanier and Thunberg. The format remained unchanged, and the only thing that had altered in a decade was the selection of the people. "That is maybe why I had not done it for a while," he says.

You have to remind yourself: 'I know this feels important now, but there is a very good chance it will feel completely unimportant in five years time'Adam McEwen

"In the last three or four years we have been living in a very different world ..." McEwen says. "Suddenly it felt interesting to ask myself who is important to me ... [Thunberg, Sadhguru and Lanier] cover three huge bases of thought and activity. Greta Thunberg is obviously foregrounding [climate change], something we are all thinking about. Sadhguru is an emblem of a notion—what are we engaged in with Western industrial capitalism? Why are we working? Is there an alternative? Jaron Lanier [shows] we are sliding into this very strange digital reality, led by profit."

The personalities McEwen chooses "need to have a permanent value at the time. ... You have to remind yourself: 'I know this feels important now, but there is a very good chance it will feel completely unimportant in five years time' ... Time changes one’s position to the subject. It is prismatic."

When he made a hypothetical piece on Ang San Suu Kyi in 2011 she was globally recognised as a pro-democracy heroine. "Three, four years later, that story had shifted in a way that would have been very hard to predict," McEwen says. "That makes the artwork even more insecure. [It] is standing on shifting grounds. That’s interesting. It means the relation between viewer, artwork and reality, which is already illusory and nebulous, just becomes even more so."

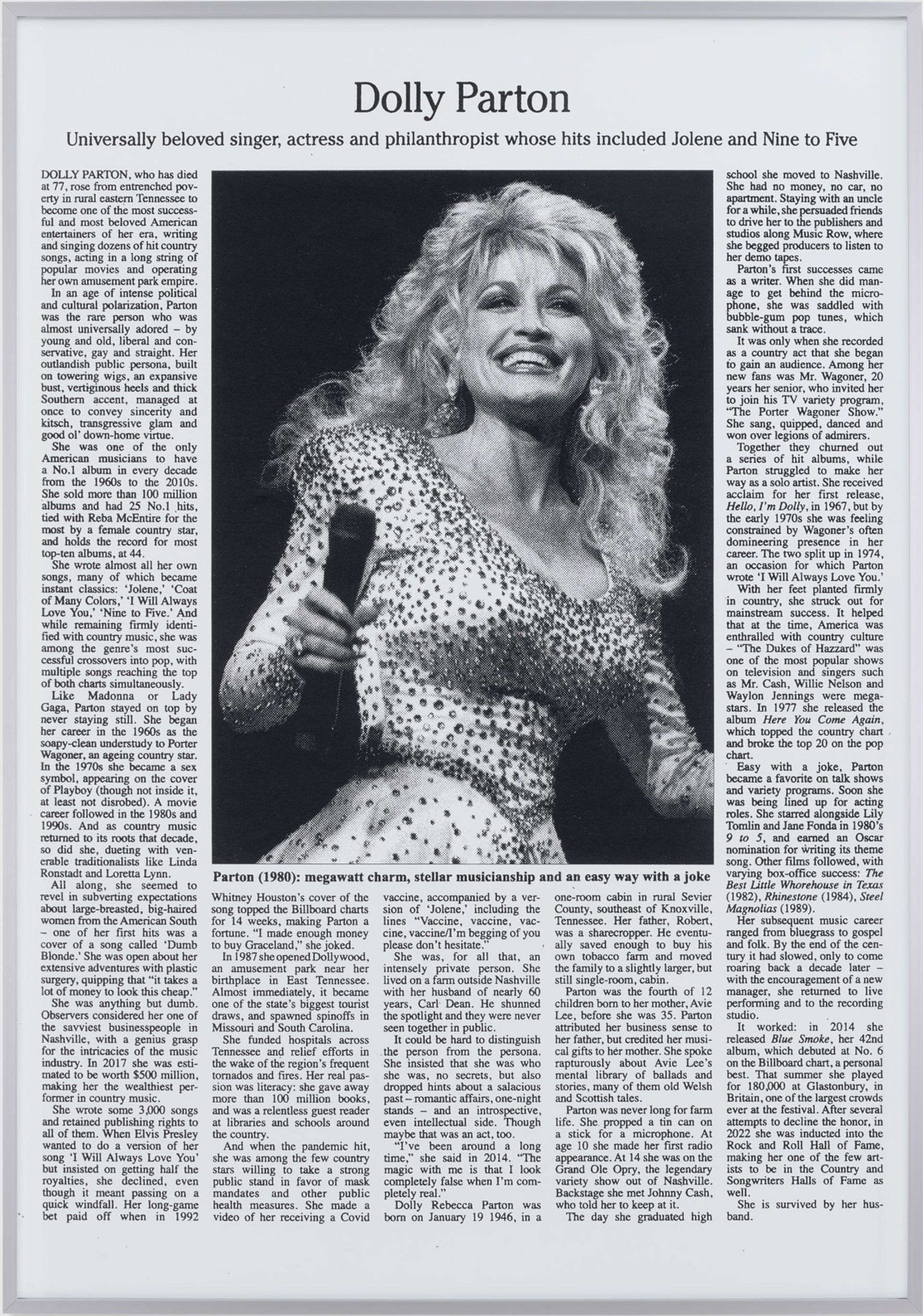

McEwen's Untitled (Dolly) (2023) © Adam McEwen. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Courtesy Gagosian

McEwen's London show includes pieces—a 2015 charcoal drawing on paper; a 2023 sculpture in milled steel, Rain Puddle—that reflect other sides to the wide-ranging practice he has developed over the past 20 years. It covers conceptual, sculptural and installation work, including facsimiles of everyday items—jerry cans, ATM machines, clocks, air-conditioning units, safes—in graphite, sponge and other materials. Those "everyday" pieces, he said in 2018, make a "very familiar object, momentarily unfamiliar". The "momentarily unfamiliar" is an effect that he achieved with his "Sorry" works two decades ago and that he generates to this day with the scale, and hypothetical nature, of his obituary works.

The London exhibition runs concurrently with Adam McEwen XXIII, at Gagosian Rome, a series of paintings inspired by the artist's love of ballpoint pens. In this new body of work, McEwen frames the "ballpoint pen as seen through the lens of very early [Roy] Lichtenstein or Dada or mechanical drawing". He has been thinking about this approach, he says, for 10 years. "The simplicity of very early Lichtenstein. What if I draw this pen in that style? Maybe it is going to speak to a lot of people."

We are all more powerful than we think. We have the choice to say 'No'. We have the power to negotiate the factors that seem to have control over us. They don’tAdam McEwen

An unchanging format

By keeping the format and typography, and the understated, impersonal, authorial voice, of his obituary pieces unchanged for more than 20 years, McEwen has allowed himself "a kind of distance" that places the changes in his choice of personalities—and the types of decisions they have made in their lives—in even stronger relief.

McEwen's piece on David Hammons, an artist he particularly admires, has a special meaning for him. The subheading reads: "Artist whose poetic vision rooted in Black American culture produced works of confounding power." The main article text testifies to McEwen's awareness of the work, of that confounding power, and demonstrates the neutral crispness of his "dry, understated" 1990s Telegraph style.

McEwen's sculpture Rain Puddle (2023) and his hypothetical obituaries of David Hammons, Marc Almond, Grace Jones and Jaron Lanier. Gagosian, Davies Street, London © Adam McEwen. Photo: Lucy Dawkins. Courtesy Gagosian

Hammons's work, McEwen writes, "could also be searingly caustic as in the torched and paint-slathered fur coats he exhibited, in collaboration with his wife Chie Hasegawa, in a blue-chip gallery on New York's Upper East Side in 2007; or kaleidoscopic in meaning, as in 'Higher Goals' (1983), a fifty-five foot tall basketball hoop in an empty lot in Harlem."

When asked what he wants people to come away with from his London show, McEwen is typically deliberate and thoughtful in his answer: "That they would understand that we are all more powerful than we think," he says. "We have the choice to say 'No'. We have the power to negotiate the factors that seem to have control over us. They don’t."

"Look at someone like Dolly Parton or David Hammons, an incredible artist," McEwen says. "These are people who did not 'buy it'. [They thought] ‘I am going to show myself that I can change the rules.’ And then they did it. These guides are rule-changers.”

• Adam McEwen, Gagosian, Davies Street, London W1, until 11 March

• Adam McEwen XXIII, Gagosian Rome, 10 February-1 April

• Louis Jebb is managing editor of The Art Newspaper and oversees the publication's obituary coverage. He was deputy obituaries editor of The Independent newspaper from 1989 to 1995.