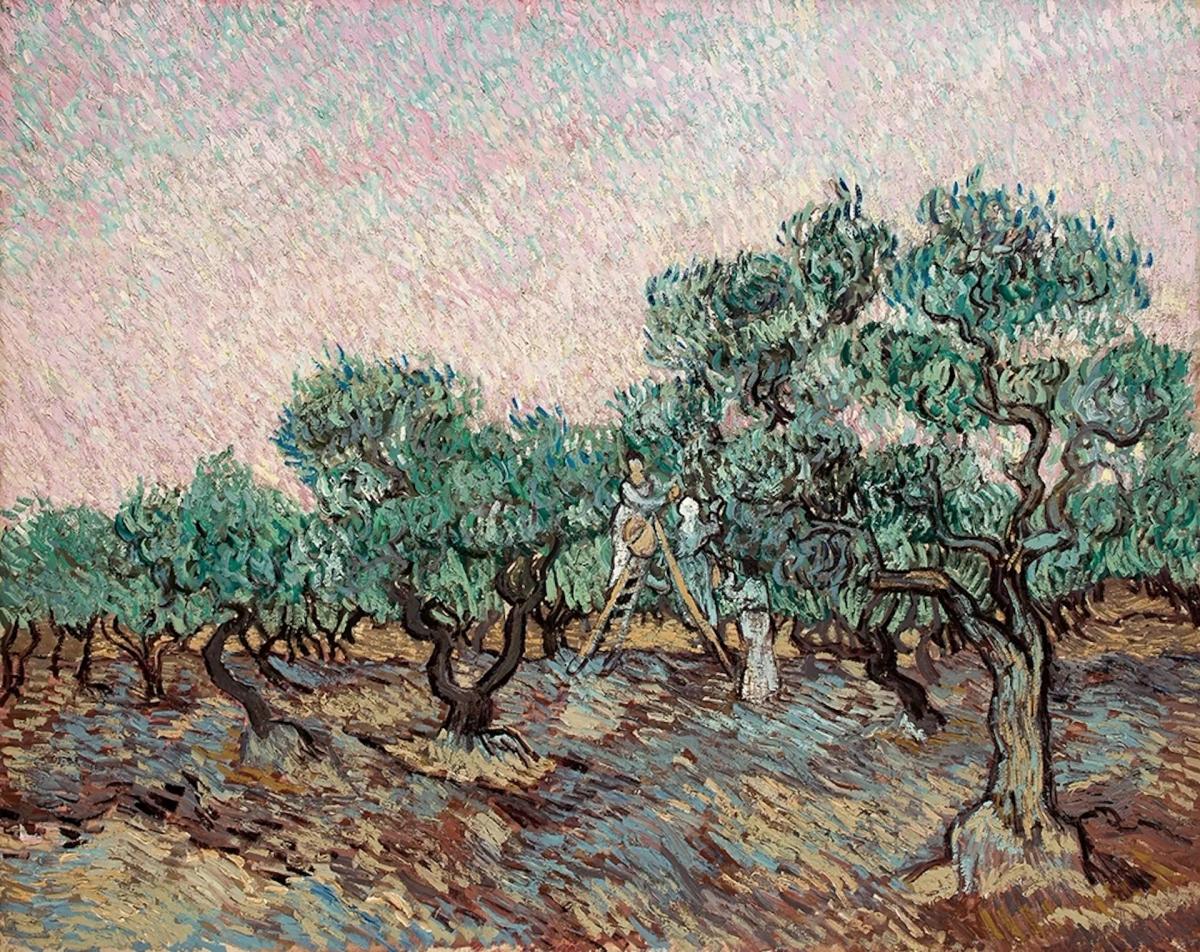

A restitution claim alleges that a major Van Gogh landscape belonging to an Athens museum was subject to a forced sale in Hitler’s Germany. Olive Picking (1889) was a key loan in last year’s exhibition Van Gogh and the Olive Groves in Dallas and Amsterdam, although the legal action was only initiated in December, after the painting’s return to Greece.

The lawsuit concerning Olive Picking was filed just two days after the heirs of Paul Mendelssohn-Bartholdy called for the return of the Sunflowers (December 1888-January 1889) from Tokyo’s Sompo Museum.

Nine heirs of the Munich-born collector Hedwig Stern are suing the Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation in Athens and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for the return of Olive Picking. Stern bought the painting in around 1935 and lost it the following year after she fled Nazi Germany. It was later acquired by the Met and subsequently deaccessioned, before it was acquired by the Greek shipping tycoon Basil Goulandris (d. 1994) and his wife Elise (d. 2000).

Although the legal complaint and subsequent media reports have valued Olive Picking at “more than $75,000”, it is worth a great deal more. We can report that the painting would be valued at many tens of millions of dollars. Another of the artist’s Provençal landscapes, Orchard with Cypresses (April 1888), sold for $117m at Christie’s last November.

Olive Picking is now a star exhibit at the Athens museum of the Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation. Their museum, which opened in 2019, houses two other important Van Goghs: Still-life with Coffee Pot (May 1888) and Les Alyscamps (October 1888).

Catalogue book cover of The Collection of the Basel & Elise Goulandris Foundation: Modern Art by Marie Koutsomallis-Moreau (2019) Basel & Elise Goulandris Foundation, Athens

Van Gogh painted three slightly different pictures of women picking olives in the autumn of 1889, while living at the asylum on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. The Goulandris version was the first, painted outdoors in the olive groves in November 1889, and is the most spontaneous of the trio. Two others were painted a month later, back in the artist’s studio room in the asylum, and they are more stylised.

Vincent referred to the Goulandris picture in a letter to his brother Theo in April 1890 when he sent a consignment of works to Paris, writing: “You’ll find that the olive trees with the pink sky are the best.”

By 1912, Olive Picking had been acquired by the Munich-based collector Alfred Wolff and his wife Hanna. Until recently it was unclear when they sold it, but it now seems that it was in 1935, through the Berlin-based Thannhauser gallery. The Van Gogh Museum published research on the painting’s provenance in a 2017 study on Thannhauser edited by Stefan Koldehoff and Chris Stolwijk, with research by Monique Hagemann.

Hedwig and her husband Fritz, a doctor, were both Jewish and faced increasing persecution by the Nazi regime in the 1930s. In December 1936 they fled Germany, emigrating to the United States.

The Gestapo barred the Sterns from exporting their art collection. Soon after their departure, the Nazi authorities ordered their lawyer, Kurt Mosbacher, to sell their art for the benefit of Hitler’s government. In early 1938, he arranged for the Thannhauser gallery to sell the Van Gogh and a Renoir also owned by the Sterns. Both works were bought by the Potsdam-based artist Theodor Werner, who paid 55,000 Reichsmarks for the pair (then equivalent to around £4,500). The money was transferred into a blocked Stern bank account and in January 1939 its funds were seized by the Nazis.

What then happened to the Van Gogh during the war? Werner was declared by the Nazis to be a “degenerate” artist and most of his work was destroyed by Allied bombing. It seems that he may have shared ownership of Olive Picking with the Thannhauser gallery’s owner Justin Thannhauser, who could have cared for it during the war. The dealer left Germany for Paris in 1937 and four years later he moved to New York.

In 1948 Thannhauser sold Olive Picking to Vincent Astor, an heir to the vast Astor family fortune. The dealer was himself Jewish and knew Stern personally, so he should surely have realised the circumstances behind her 1930s sale.

Astor sold the Van Gogh to the Metropolitan Museum of Art via a dealer in 1956. The Met kept the painting until 1972, when it was controversially deaccessioned in order to raise funds for other acquisitions. It apparently sold for $850,000. Two decades later, its former director Thomas Hoving commented that the painting was “not good enough for the Met with so much in Post-Impressionism”.

The present legal claim is being pursued in the US District Court for Northern California in Oakland. Lawyers for the Stern heirs, the Santa Monica-based Kohn Law Group, argue that Hedwig Stern (who died in California in 1987) was deprived of the painting and that it should be restituted to her inheritors. Their claim is backed up by a 83-page research report by Jonathan Petropoulos, a US historian specialised in Nazi art looting.

The Stern heirs are also suing the Met for the money it derived from the 1972 sale of the painting, alleging that the museum covered up the transaction to avoid potential restitution issues. However, when the museum purchased the Van Gogh in 1956 it was not public knowledge that it had been owned by Stern. All that was then recorded was that Wolff had acquired the painting by 1912.

The claimants argue that even if the museum’s curators did not know about the Stern loss, the fact that the work was assumed to have been in Germany in the 1930s should have been a “red flag”, leading to a close examination of its Nazi-era provenance. But it should be remembered that in the 1950s there was much less concern about Nazi “forced sales” than there is today.

It is arguably surprising that Stern and her heirs did not manage to track down the Van Gogh earlier. From 1956 until 1972 the painting was held at one of America’s greatest art museums, and the Met’s sale of the work provoked a media controversy. In 1999 the Goulandris Foundation temporarily exhibited Olive Picking in its gallery on the Greek island of Andros. But it was not until four years later that the heirs discovered the painting was owned by the Greek foundation.

After the Stern heirs filed their lawsuit in December, a Metropolitan Museum of Art spokesperson told The Art Newspaper: “At no time during the Met’s ownership of the painting was there any record that it had once belonged to the Stern family. Indeed, that information did not become available until several decades after the painting left the museum's collection.” The museum “stands by its position that this work entered the collection and was deaccessioned legally and well within all guidelines and policies”, but it “welcomes and will consider any new information that comes to light”.

A spokesperson for the Athens museum says that “the Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation has not been officially informed on any action… therefore we cannot comment on it”. The painting remains there on public display.

Van Gogh’s Women Picking Olives (December 1889), acquired by the Met in 2002, 30 years after it sold Olive Picking Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg Collection; gift, 1995; bequest, 2002)

Despite Hoving’s belief that the Van Gogh “was not good enough” for the Met, in 2002 the museum accepted the donation of one of Van Gogh’s two later versions of the same subject. Women Picking Olives (December 1889) came with the bequest of the billionaire publisher, diplomat and philanthropist Walter H. Annenberg.

This acquisition of a slightly lesser version suggests that the museum’s deaccessioning sale 30 years earlier had been a serious mistake. But had the Stern painting remained at the Met, the museum would probably have faced a Nazi-era restitution claim long ago.