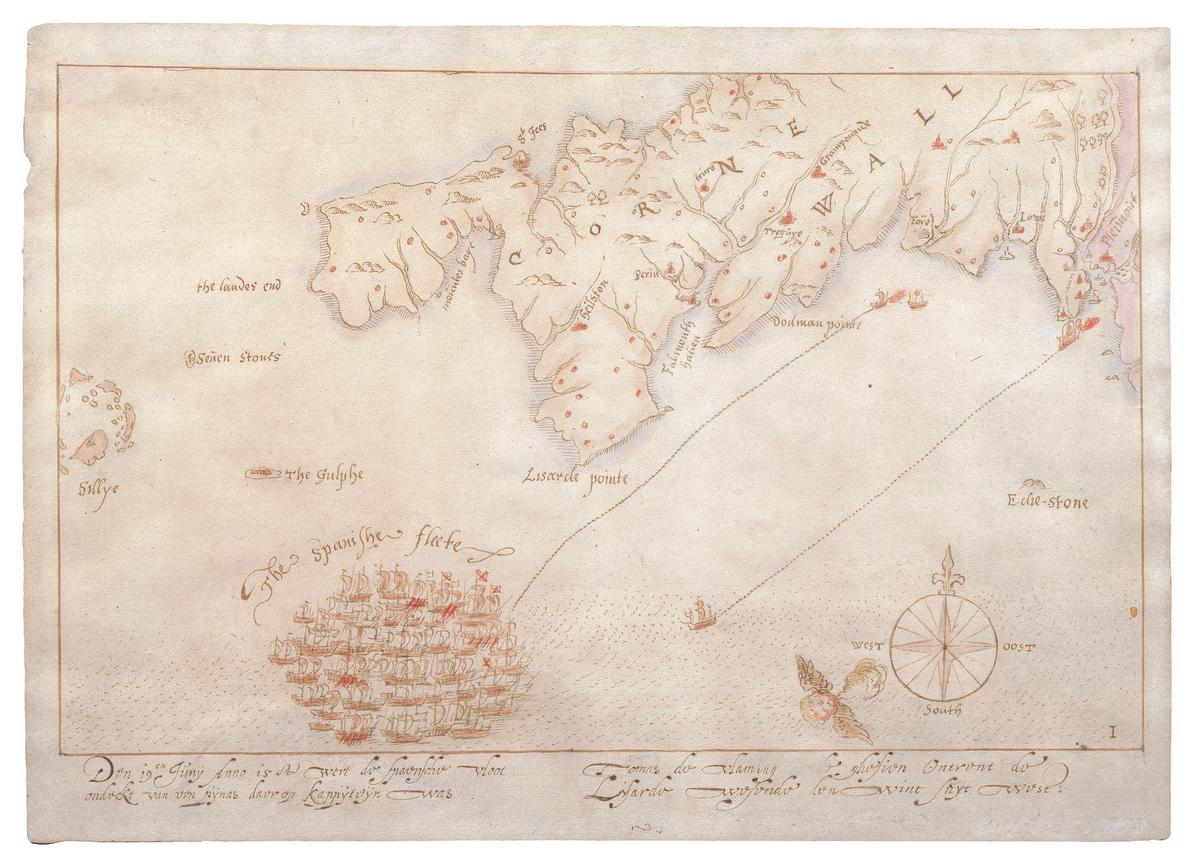

Conservation work on a unique set of 16th-century hand-drawn maps, the earliest surviving representations of the failed Spanish Armada invasion of England in 1588, has revealed that, although beautifully drawn in black ink on fine-quality paper, and of great historic importance, they were judged insufficiently attractive for a late 19th-century sale. The map's convincingly antique, delicate shades of red were added either for an auction or by the book dealer who bought them and sold them on at a handsome profit to the Astor family.

Last year, the maps were sold by the Astor estate but the government barred their export to a US collector because of their heritage value. Dominic Tweddle, the director of the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Portsmouth—the map includes a tiny image of the city in its depiction of a skirmish off the Isle of Wight—read of them over his breakfast and acquired them after raising £600,000 in just two months, including grants of £212,800 from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and £200,000 from the Art Fund.

The threatened Spanish invasion in the summer of 1588, by an Armada of 138 Spanish warships, struck terror in England, but the smaller English fleet proved quicker and more mobile. The maps track the series of battles fought off the coast, some within sight of land, before the weather intervened on the English side and autumn gales scattered the Armada; dozens of the ships were wrecked off the Scottish and Irish coasts as they limped homeward. The maps, certainly based on eye-witness accounts, may have been commissioned by Admiral Lord Howard of Effingham, but his final account used a set of engravings by the royal cartographer Robert Adams and the engraver Augustine Ryther—the British Museum has a complete set—which had already been published.

The maps are generally in good condition, though one has traces of repaired mould and water damage after a flood in the 1960s at their former home at Hever Castle in Kent. The complete set was sent by the museum to the National Archives in London for study and a condition assessment, the first time the two institutions have worked together.

Dominic Tweddle, the director of the National Museum of the Royal Navy, raised £600,000 in two months to prevent the maps’ export to the US Photo: National Museum of the Royal Navy

Flemish watermarks

Non-invasive tests including x-ray fluorescence spectroscropy revealed Flemish watermarks, which, with some marginal notes, suggests a craftsman probably working in London at a time when the Flemish were recognised as the best cartographers in Europe. The iron gall ink was 16th century and in good condition despite slight fading and paper corrosion—but the surprise was the reds, only available from the late 19th century. “The only possible conclusion was that the original maps were not coloured,” says Natalie Brown, the senior conservation manager at the National Archives. The work has implications for hundreds of antique maps in their own collections.

At the museum, curator Annabelle Cameron says that, while 300 years of their history remains unrecorded, by the early 19th century the maps were owned by Roger Wilbraham, the collector and MP—and may always have been in his family—and were seen by the British Library in 1828. They were sold by Sotheby’s in 1899 to the bookseller J. Pearson and Co, who sold them in turn to William Waldorf Astor in 1903. Either could have added the coloured ink to make them more attractive, which Brown said was common practice at the time. It certainly helped bump up their price: Pearson paid £30 for the maps and sold them for £90.

“The good news for us is that the maps are stable, and so can be exhibited, for short periods, in carefully light-controlled conditions,” Cameron says. “I really love them; they’re beautiful things.” Two were on temporary loan to the Walker gallery in Liverpool last summer, but the Portsmouth museum hopes to display all ten as soon as they can.