Renowned for painting young women, love letters, musicians, pearls and glasses of wine, Johannes Vermeer appears to us as a rather secular artist, capturing the pleasures of life. But a new biography, due to be published later this month, presents him as a staunch upholder of the Jesuit order of the Catholic church.

Gregor Weber, the head of fine arts at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, has written Johannes Vermeer: Faith, Light and Reflection. He believes the book will “overturn conventional understanding of the artist and his work". His biography is being published by the museum ahead of its ambitious Vermeer survey exhibition, co-curated by Weber, which opens on 10 February.

Vermeer was brought up as a Protestant in the Dutch Reformed Church. Although it has long been known that his wife Catharina Bolnes was a Catholic, the full extent of his commitment to her religion may come as something of a surprise.

After their marriage they lived in a neighbourhood of Delft known as Papist's Corner (Papenhoek) and all of their 15 children were raised as Catholics. One son was named Ignatius, after the Spanish founder of the Jesuits, Ignatius of Loyola. The building next to their home was a Jesuit mission, which included a church with seating for 700 worshippers.

Weber writes: “Johannes and Catharine raised their children in that faith, following the requirements set by the Church… Thus, the assumption that he, too, converted to Catholicism becomes even more probable.”

Weber points to several of Vermeer's 37 surviving paintings as evidence of his adopted religion. Most obvious is his Allegory of the Catholic Faith (around 1670-74, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), completed shortly before his death. A picture of the Last Judgment, a reminder of the importance of Christianity, hangs in the background of the earlier work Woman Holding a Balance (around 1662-64, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC).

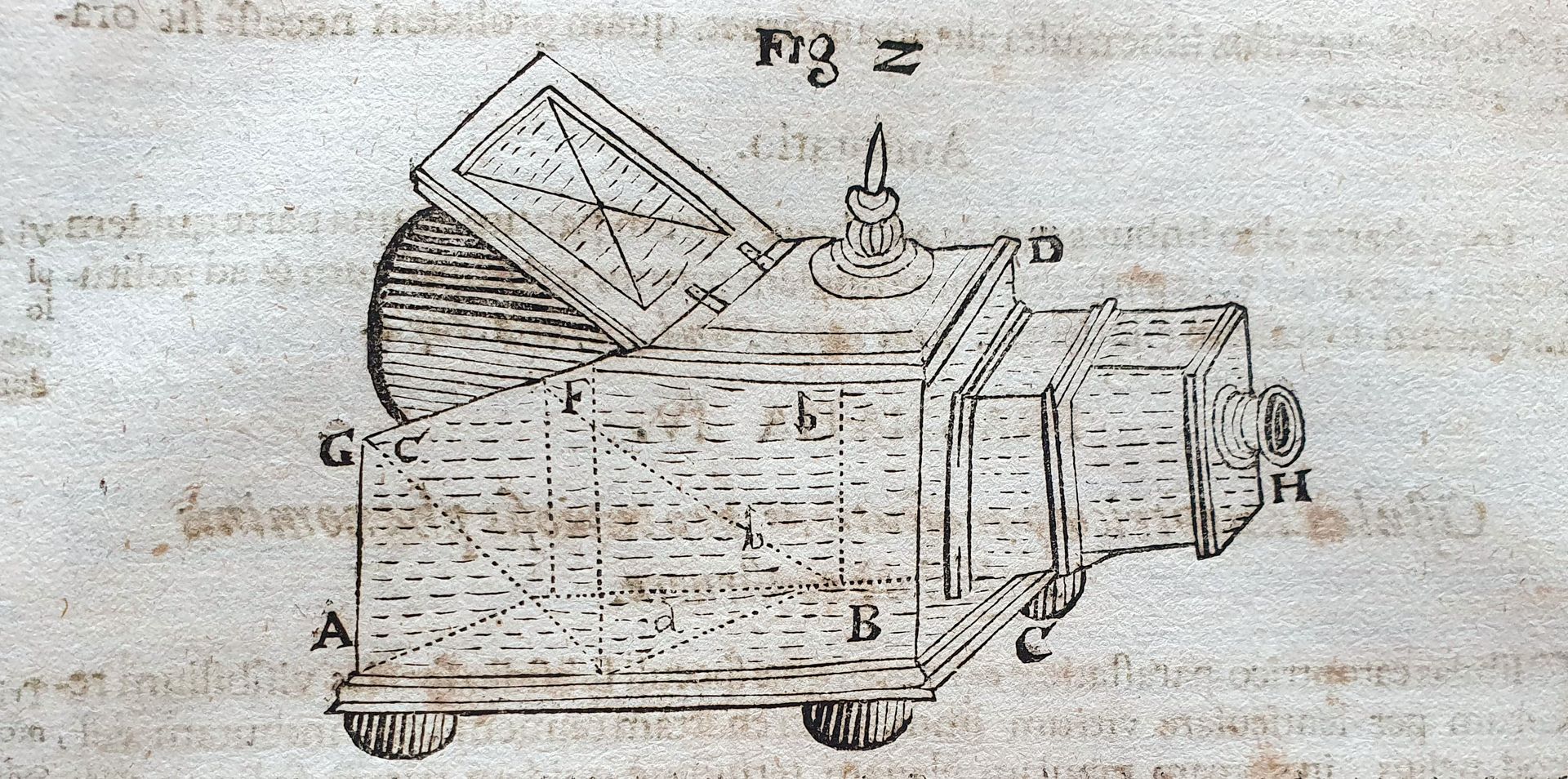

An illustration of a camera obscura, from Johann Zahn Oculus, artificialis teledioptricus, Neurenberg (1669) Image: Utrecht University Library

Research for the book uncovered further evidence to support the controversial view that Vermeer used a camera obscura to help him compose his interior scenes. Weber discovered a portrait drawing by a priest from the neighbouring Jesuit church, Isaac van der Mye, who was also an artist. Recently identified in the Rijksmuseum collection, it dates from around 1650 and depicts an elderly woman as St Apollonia. Weber believes that it was probably drawn using a camera obscura, by projecting an image from below onto a glass disk, on which the thin parchment was placed for tracing. Weber speculates that Vermeer could have acquired Van der Mye’s camera obscura after the priest’s death in 1656.

He goes on to write: “Light and optics were a major focus of Jesuit devotional literature: the order regarded the camera obscura as a tool for the observation of God’s divine light. There is even a sermon that explores in detail the artistic and moral aspects of the camera obscura.” He points to Vermeer’s likely use of such a device in The Lacemaker (around 1666-68, Musée du Louvre, Paris), where the objects in the foreground of the painting appear blurred.

Today we enjoy seeing Vermeer’s depictions of young women in domestic interiors, such as his Woman with a Pearl Necklace (around 1662-64, Berlin State Museums), without usually considering them in a religious context. To 21st-century eyes, his beautifully crafted interior scenes offer up tranquil and elegant pleasures of wine, women and song. However, as Weber's research reveals, Vermeer's careful compositions are often metaphors for the transience of worldly things.