Amid the rising global chorus of calls for repatriation of ill-gotten artefacts, museums all over the US have been compelled to grapple with the colonial brutality undergirding some of their collections. This institutional introspection has included closer auditing and examination of Indigenous artefacts, many of which entered museums during a chillingly non-consensual chapter of “ethnographic” collecting and curation in American history.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), adopted in 1990, requires government-funded institutions to acknowledge their ownership of Native human remains and sacred objects. So far, according to the National Parks Service, less than half of the more than 200,000 objects catalogued have resulted in receipt of stolen cultural property by the 574 federally recognised tribes affected, a figure that reflects a constellation of legal loopholes, bureaucratic red tape and institutional inertia. This makes the Founders Museum, a tiny library collection located in Barre, Massachusetts, an anomaly in the conversation: following accusations that it was "hoarding" Indigenous artefacts, the museum facilitated the return of more than 150 objects to the Lakota and Sioux tribes in an official repatriation ceremony held at the museum earlier this month.

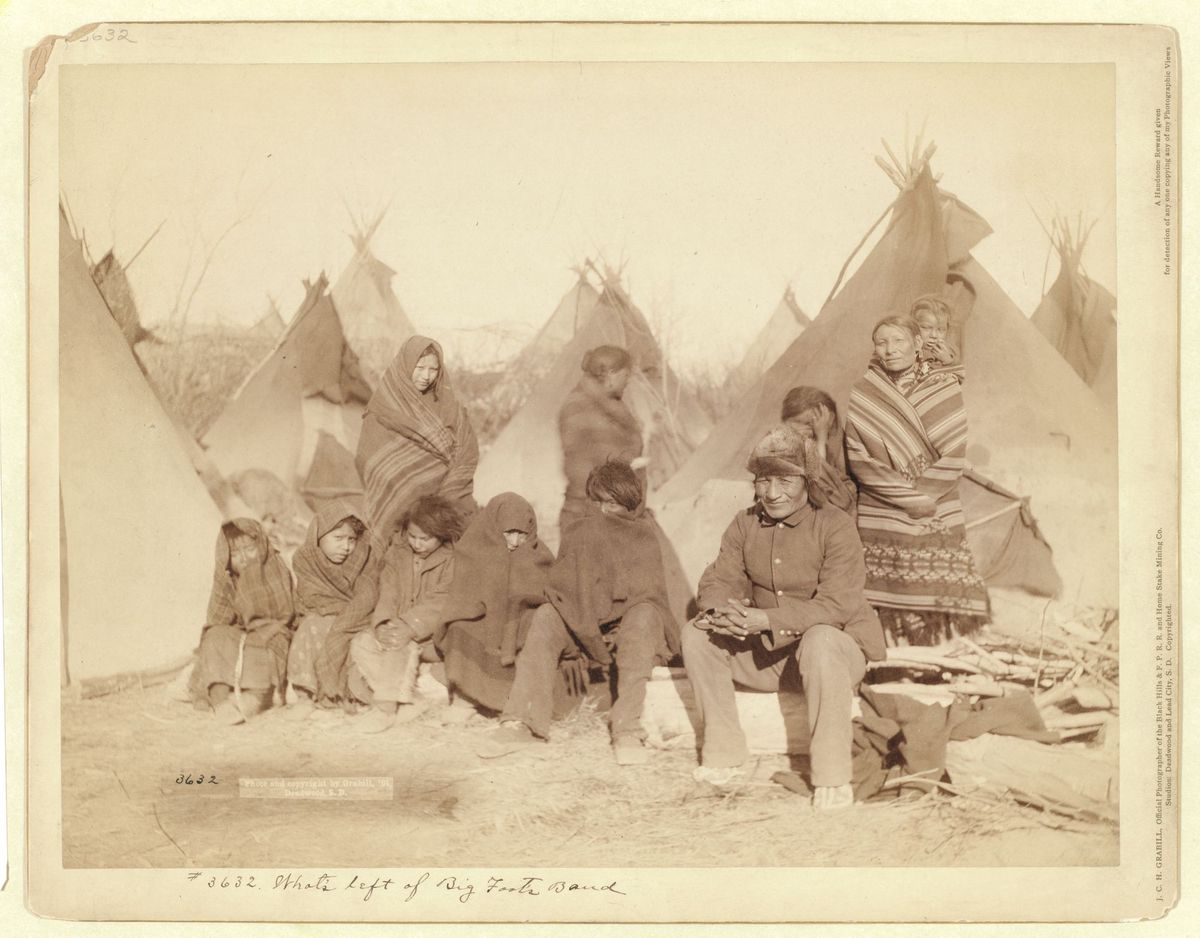

Tribal members received clothing, weapons and pipes, some of which date back to the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre, an ambush by US cavalry in which more than 250 Lakota men, women and children were killed. This hard-won handover represents the culmination of a nearly three-decade institutional effort, challenged by “third party interference” and member disavowal, museum president Ann Meilus told Artnet News.

In 1993, the Woods Memorial Library Association, which then oversaw the Founders Museum, agreed that the items would be returned to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Representatives of the Sioux nation then created a plan to seek funding from the National Endowment for the Arts to pay Sioux artisans to make duplicates of the artefacts, ensuring that the Founders collection remained tangible to visitors and creating Indigenous employment opportunities in the process. Those plans were never realised.

In January of this year, Meilus renewed efforts to repatriate the artefacts. While NAGPRA protocols don’t technically apply to the museum as it does not receive federal funding, Meilus took inspiration from the act as a guide for her restitution efforts, arranging for the items to be appropriately photographed and tested for arsenic and mercury, compounds that were historically often used to preserve animal hides.

Following visits from Mia Feroleto, editor and publisher of New Horizon magazine and official representative of the Oglala Sioux tribe, members of the Barre Museum Association voted to continue with repatriation efforts under the guidance of NAGPRA specialist Aaron Miller. “We just wanted to do the right thing and help the Lakota people heal from the tragedy they suffered,” Meilus told Artnet News, adding that the Founders Museum has “one of the most pristine collections of Native American artefacts in the country”.

A large portion of the museum’s collection was sourced in the late 19th century from Frank Root, a traveling shoe salesman and circus impresario who, according to the Associated Press, acquired the objects directly from soldiers in the aftermath of Wounded Knee. While Pine Ridge resident, Surround Bear, told The Boston Globe that the gesture constituted a “step towards healing”, the work is not over. By Meilus’s own admission, the repatriated pieces represent only a quarter of the museum’s holdings, extracted from over 60 different tribes around the country.

While the Founders Museum has been proactive about provenance research and repatriation, other restitution efforts have progressed more slowly—or not at all. In a 2 November speech to trustees, British Museum chair George Osborne once again rejected calls for the return of the Parthenon Marbles to Greece. The Digital Benin platform, an online resource cataloguing objects looted from southwest Nigeria’s Edo Kingdom, represents an important step in the direction of ethical asset repatriation. And earlier this month the Peabody Museum at Harvard University admitted it owns a collection of hair samples taken from Native American children at state-sponsored boarding schools in the 19th century, insisting in an official apology that restitution efforts have been initiated.