It was a tale of two auctions at Sotheby’s New York on Monday night (14 November), with a strong result for a single-owner sale of works from the collection of the late Whitney Museum president David Solinger (1906-1996) followed by a humdrum evening sale of Modern art. The combined results brought in a total hammer sum of $336.3m ($391.2m with fees), though the 23-lot Solinger sale performed far better against expectations compared with the 44-lot Modern evening auction.

A connoisseur’s collection

The Solinger collection auction was a sold-out, white glove affair, bringing in a hammer total of $116.3m ($137.9m with fees), near the upper end of Sotheby’s pre-sale estimate range of $86.7m-$118m (estimates do not include auction house fees). Remarkably for a major single-owner sale in this era, none of the lots in the Solinger trove were backed by guarantees or came with irrevocable bids, a sharp contrast to recent high-wattage auctions such as those of the collections of Harry and Linda Macklowe that Sotheby’s conducted in November 2021 and last May and the $1.6bn Paul Allen sales Christie’s held last week, in which every lot was guaranteed and many held irrevocable bids.

“Perhaps Sotheby’s felt that, in order to be equivalent to what was going on at Christie’s with the Paul Allen collection, they needed to put their best foot forward in terms of presenting a collector who was comparable,” the New York-based adviser Beverly Schreiber Jacoby says. “Even though the dollar amounts may not be the same as with the Allen collection, Solinger is a collector who was also a very committed and significant art world participant.”

Solinger’s involvement in the art world—as the president of the Whitney who was instrumental in the construction of its former Marcel Breuer building on Madison Avenue, as a lawyer representing many famous artists and as a formally trained painter—may have contributed to his collection’s auction performance. All but a handful of lots saw competitive bidding, and nearly half (11 of 23) sold for hammer prices above their high estimates.

The sale opened dynamically, with sculptures by Jean Arp and Alexander Calder and a painting by the Pittsburgh-born modernist William Baziotes all exceeding their estimates. The Calder in particular, Sixteen Black with a Loop, a classic mobile from 1959 that hung over the saleroom, quickly surpassed its high estimate of $4m to sell for a hammer price of $7.1m ($8.4m with fees). Like several of the night’s prized lots, it went to a collector in Asia.

Alberto Giacometti, Trois hommes qui marchent (grand plateau), 1952 Courtesy Sotheby's

Alberto Giacometti’s handpainted bronze sculpture Trois hommes qui marchent (grand plateau) (1952) was among the sale’s highest-priced works and quickly marched right past its $20m high estimate. It eventually hammered at $26m ($30.1m with fees), with a bidder in Sotheby’s York Avenue saleroom prevailing over three phone bidders.

Two lots later, the work with the Solinger sale’s highest estimate, Willem de Kooning’s brilliant, intricate Collage (1950, est $18m-$25m), set off a bidding war among collectors on the phones with four different specialists. In the end, the client on the line with Sotheby’s senior vice president in New York Bame Fierro March landed the lot with a $29m bid ($33.6m with fees). That result set a new record for a De Kooning work on paper, though his paintings have fetched much higher sums at auction (his Untitled XXV from 1977 sold for $66.3m, with fees, at Christie's in 2016) and in private sales (mega-collector Ken Griffin reportedly paid entertainment mogul David Geffen $300m for the 1955 painting Interchange).

Willem de Kooning, Collage, 1950 Courtesy Sotheby's

The rest of the Solinger sale saw solid results, though a suite of works by Paul Klee mostly failed to spark much interest, and one of the collection’s star lots, Pablo Picasso’s Femme dans un fauteuil (1927, est $15m-$20m), sold after just one bid for a hammer price of $8.4m ($9.9m with fees). Grimly, the sale’s third-to-last lot appeared to benefit from the so-called “death effect”: Peinture 92 x 65 cm. 7 février 1954 (1954, est $800,000-$1.2m), a prismatic black-on-gold composition by Pierre Soulages, the French abstractionist who died last month at age 102, set off a contest between nine bidders and eventually sold for $2m ($2.4m with fees) to a collector on the line with Sotheby’s Los Angeles-based private sales specialist Jacqueline Watcher. (The same bidder also snapped up a small, crimson Klee work on paper earlier in the sale.)

No second wind

After a brief intermission following the Solinger sale, Sotheby’s Europe chairman Oliver Barker returned to the rostrum for the Modern evening auction, although many of the energetic bidders from earlier in the evening seemed to have opted for dinner instead. The second auction came with significant financial guardrails: 25 of the 44 lots were guaranteed and 21 had irrevocable bids. Some of the lots also benefited from provenance comparably stellar to the Solinger sale: four of the lots, including a major Picasso, were coming from the collection of the late Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) president William S. Paley (1901-1990) and being sold to benefit that museum and other charitable organisations.

Despite all the encouraging signals, the sale was a disappointment, with eight lots failing to sell (including an André Derain landscape from Paley’s collection) and two more withdrawn before the auction. In the end, the sell-through rate was 82% by lot, bringing in a total hammer price of $220m ($253.3m with fees), well below the pre-sale estimate of $232m-$287.5m.

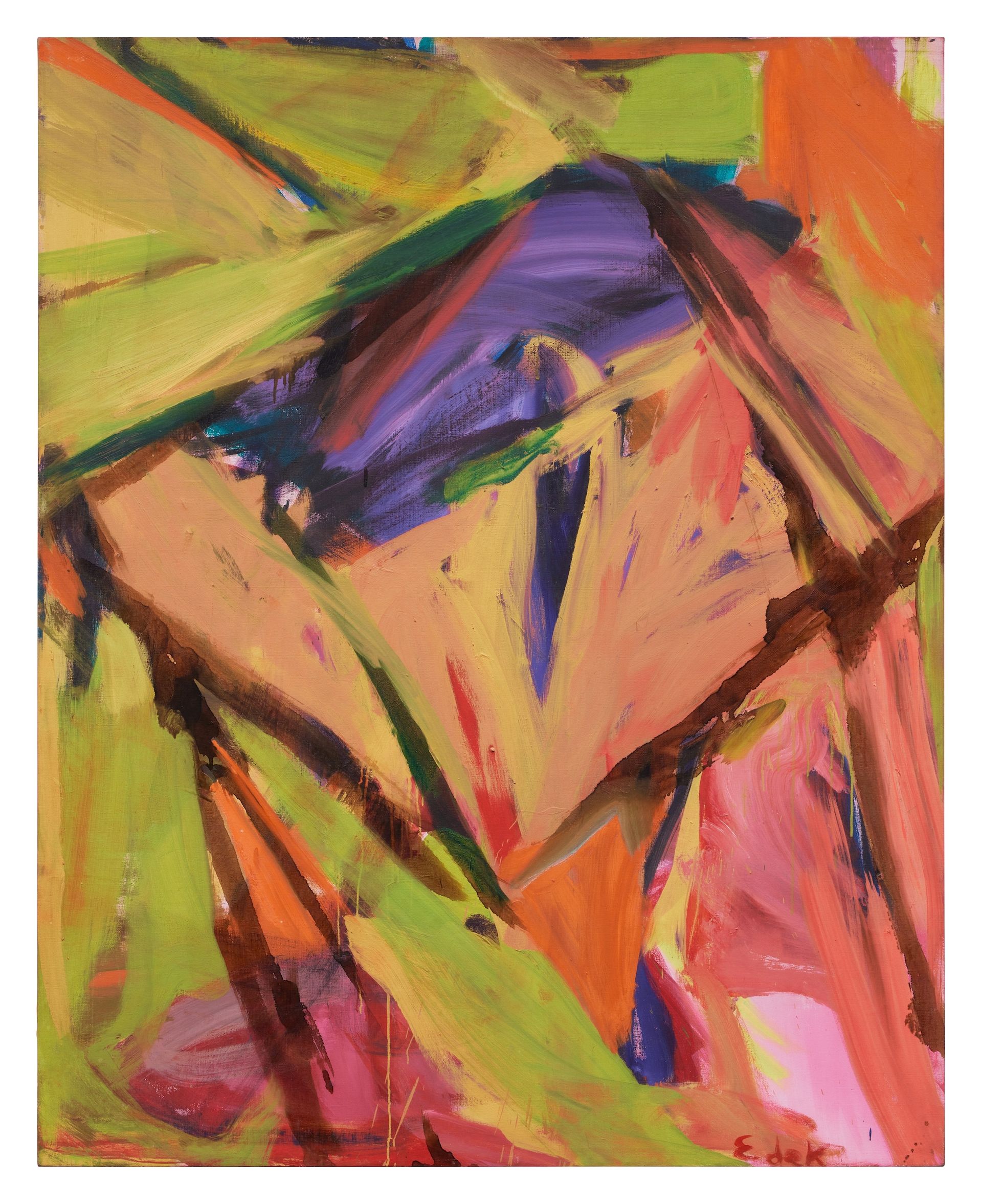

Elaine de Kooning, Charge, 1960 Courtesy Sotheby's

Even so, the auction notched some notable results, especially for women artists. It opened with an ecstatic Elaine de Kooning painting, Charge (1960), which quickly surpassed its $600,000 high estimate to sell for a hammer price of $850,000 ($1.1m with fees), a new record for the Abstract Expressionist’s work. A dazzling 1928 portrait by Art Deco master Tamara de Lempicka depicting the Greek-born duchess and arts patron Romana de la Salle sold for a $12m hammer price, firmly within its $10m to $15m estimate. With fees, the price came to $14.1m, good for De Lempicka’s second-highest auction result to date.

The sale’s star lot, a classic canvas from Piet Mondrian’s De Stijl period, Composition No. II (1930), arrived with an on-request estimate of at least $50m. It had last appeared at auction in 1983 at Christie’s in London, where it was acquired by a Japanese bank (it was subsequently sold, via Acquavella Galleries, to the present seller).

Piet Mondrian, Composition No. II, 1930 Courtesy Sotheby's

“The market is very different today than it was in 1983,” Jacoby said before the auction. “If it’s coming up for sale at this moment, it means that there is someone who has been identified already as a potential buyer.” In the end, there appeared to be exactly one someone interested in buying the Mondrian. It sold for a hammer price of $48m ($51m with fees) to a collector in Asia who placed a solitary bid via Sotheby’s chairman for Switzerland Caroline Lang. Even so, the result was good enough to set a new auction record for the Dutch Modernist’s work.

The biggest lot of the night from Paley’s collection, the Picasso still life Guitare sur une table (1919), had previously been on long-term loan to MoMA. It quickly surpassed its on-request estimate of at least $25m thanks to a two-way bidding war between collectors on the phones with Sotheby’s head of private sales for the Americas Courtney Kremers and the auction house’s senior vice president in New York Brad Bentoff. The latter’s client eventually prevailed with a winning bid of $32m, which came to $37.1m with fees.

Pablo Picasso, Guitare sur une table, 1919 Courtesy Sotheby's

That was the auction’s eighth lot, and thereafter the going got rocky, with works by canonical artists including Schiele, Degas, Rodin and Pissarro failing to sell. Several more lots hammered well below their low estimates after just one bid, including two of the sale’s biggest trophies. Giacometti’s 1962 portrait of his muse, Caroline (est $15m-$20m), elicited just one bid, hammering at $14m ($15.9m with fees). Three lots later, the actually and symbolically huge Henry Moore sculpture Reclining Figure: Festival (1951)—which was commissioned by the newly formed Arts Council of Great Britain as a sculptural centrepiece for the Festival of Britain in 1951—failed to spark any festivities. It sold after just one bid for a hammer price of $27.5m ($31m with fees), well short of its $30m to $40m estimate.

Apparently sensing the slackening mood in the increasingly sparse saleroom, Barker moved swiftly through the latter half of the sale. He fielded just five bids across the auction’s eight final lots, half of which did not sell.

The evening’s dichotomous results seemed to reinforce some of the lessons taken from the last several auction cycles, while challenging others. The success of the Solinger collection appeared to confirm the power of packaging sales around a single, visionary collector or collecting couple. But the performance of Solinger’s non-guaranteed collection, in contrast to the mixed results for the many guarantee-backed lots in the Modern evening auction, may also reflect the procedural quality of auctions with a majority of guaranteed lots, which can feel like private sales carried out in public.

Following Sotheby’s mixed results on Monday, attention shifts to Phillips for Tuesday’s (15 November) evening sale of 20th century and contemporary art, followed by Sotheby’s contemporary and ultra-contemporary evening sales on 16 November and Christie’s back-to-back sales of 20th and 21st century art on 17 November.