It is rare for an artist to hit their stride early in their career. Most experiment with genre and technique before developing what we now consider their mature styles: Mondrian first painted landscapes; Lichtenstein tried Abstract Expressionism before moving into Pop. How then do we—and the market—judge the earliest work of great artists?

Soon about to find out are two such works by Andy Warhol—Living Room and Nosepicker I—both of which will be included in a contemporary art sale at Phillips in New York City on 15 November. Painted in 1948 when he was a 20-year-old commercial art student at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, the works bear no resemblance to the flat, magazine advertisements that one associates with the Pop Art movement which Warhol helped pioneer in the 1960s. Nosepicker I: Why Pick on Me (The Broad Gave Me My Face But I Can Pick My Own Nose)—the painting’s full title—looks more like an Expressionist work by an artist like George Grosz or Willem de Kooning.

There is no question that the works are by Warhol. Both are attributed to "Andy Warhol" rather than Andy Warhola (his last name at the time); they were on long-term loan to the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh before being consigned to Phillips by the artist’s nephew James Warhola.

Nosepicker I carries an estimate of $300,000-500,000, while Living Room is estimated at $250,000-450,000. These prices are far below the heights of the Warhol market, reached in May at Christie’s New York with the sale of Shot Safe Blue Marilyn for $195m (with fees). Nonetheless, they are considerably higher than the work of most 20-year-old art students.

Andy Warhol's Living Room (1948). Courtesy of Phillips

While the paintings do not resemble our popular understanding of Warhol's style, they have have "historical value" and “capture the evolution of the post-war period," according to Robert Manley, deputy chairman and co-director of Phillips's 20th century and contemporary art department. He draws comparisons between the works to those by artists older and arguably even more canonised than Warhol himself. "Living Room has been compared by some to Vincent Van Gogh’s The Bedroom. With Nosepicker I, you can certainly see the influence of masters like Jean Dubuffet [and] the effect of 20th-century titans who were working alongside Warhol, including Paul Klee."

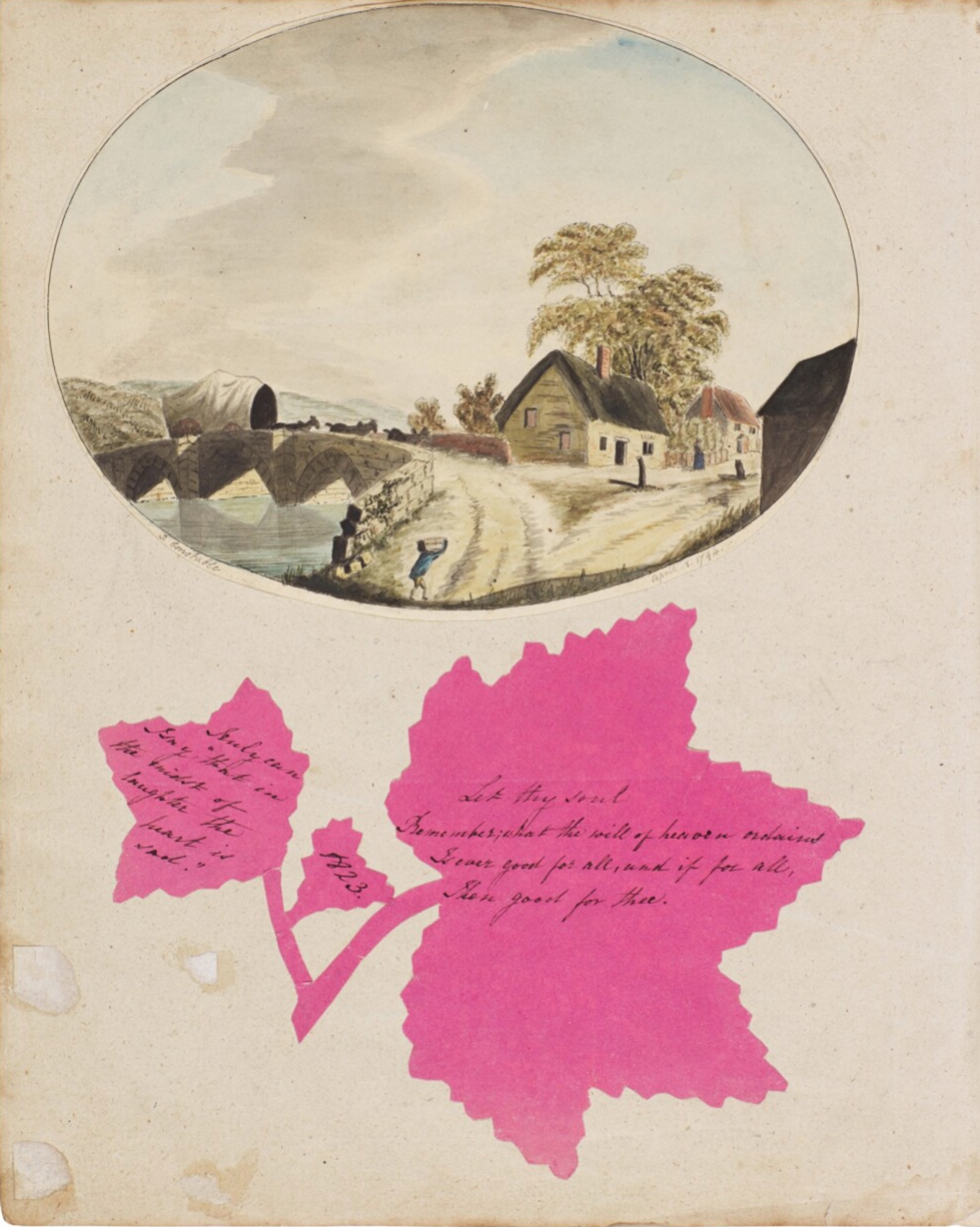

Very early work by artists is hardly a rare occurrence in galleries or at auction houses, and sometimes it garners high prices. For instance, four drawings by Constable, made when he was 17, far exceeded their estimates when they were offered at Sotheby’s London in 2020. An entire album that included the drawings, kept intact by a family related to the Constables by marriage, was estimated to sell for between £24,000 and £28,000. But just one of the works, A Rural Landscape (1794), fetched £187,000 (with fees).

John Constable's A Rural Landscape (1794). Courtesy of Sotheby's

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has a large collection of works on paper by John Singer Sargent, some of which associate curator Stephanie Herdrich referred to as “juvenlia,” meaning “art created before artists received formal art training,” which in the case of Sargent means pre-1874, when he arrived in Paris. She describes Sargent as “precocious,” adding that some of this juvenilia is on display at the museum “fairly regularly,” and these drawings “provoke wonder and amazement at what he was able to accomplish at such a young age.”

At other times, student work by artists who later became renowned is of more dubious quality. The issue of authenticating juvenilia and student work is often troublesome. Works may be unsigned, or they are atypical stylistically. “How can you tell one student’s work from another, and what if they traded works?” asks American art dealer Debra Force. At times, a studio class nude does find its way to a gallery or auction house, raising the questions of whether or not this particular artist drew or painted it. But even if there is proof that this is the work of a specific artist, does it have any inherent importance outside of the artist’s name? Would a picture of a boy sticking a finger up his nose receive a half-million dollar estimate at a major auction house if it didn’t have the Warhol name attached?

Without iron-clad documentation as to who produced a particular work and who has been in possession of it all these years, dealers like Force tend to reject would-be consignments of early work. On 18 October, the Savannah, Georgia-based Everard Auctions and Appraisals sold an untitled 1917 watercolour of a Texas landscape by Georgia O’Keeffe for $165,000 (with fees) against an estimate $100,000-150,000. According to the auction house's president Amanda Everard, “it is in the catalogue raisonné, making authenticity not an issue. Estimating its value, however, was more difficult, pointing out that this is an early work and that there are fewer works of this medium and period to enable permit price comparisons. It’s a guessing game. Sometimes, you just put things out there and hope.”

An untitled 1917 watercolour of a Texas landscape by Georgia O’Keeffe, sold in October at Everard Auctions and Appraisals.

The buyer of the O’Keeffe, Eric Andrews, owner of the Taos, New Mexico-based 203 Fine Art Gallery, says that several years earlier he had purchased another early untitled watercolour that is not included in the O’Keeffe catalogue raisonné. “I bought it from someone who got it at an estate sale,” he says. The work, Andrews says, has the artist’s signature, but not on the back of the paper that watercolour was applied, as is standard, but on the back of the matting. "I showed it to someone at Sotheby’s who said it looked right," but Andrews is waiting for more definitive authentication before putting it up for sale. "Right now, I’m just calling it 'attributed to.'"

There may be some clues. Force says that she turns to experts—museum curators or university professors—in the work of certain artists when she has questions about an attribution. Perhaps an entry in the artist’s diary will refer to a sketch, or there may be other forms of evidence. The British-born American painter Thomas Sully (1783-1872) “was meticulous,” Force says. “He kept a registry of pretty much everything he ever did.” Family members may have saved early works or they have stories about who did what, “but family lore isn’t always correct,” she said. “Someone will come in, saying his mother was an artist who worked with a well-known artist, and she said that the artist gave this to her. That can be difficult to prove.”

Other problems arise when selling early works too. According to Angelo Madrigale, senior vice-president in charge of paintings at Doyle auction house in New York City, there can be “pushback” from the artists themselves or from their estates. “These aren’t works that the artists expected to exhibit, and they don’t want them to come to market.” The other concerns the expectations of the consignors who believe that “early works should be as valuable as the artist’s best known works,” whereas in fact the potential prices would be a small fraction of mature artworks. “This problem keeps many early works from coming to auction.”

Another realm of early work is copies made of other artists’ work, which was once a standard teaching lesson for art students—one continues to see artists setting up their easels in art museums to copy famous paintings. The artistic and market value of these works are difficult to assess. For instance, an Arthur B. Davies (1862-1928) copy of a landscape by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875), which was signed by Davies, sold in 1995 at Doyle Auctions for $2,000, well under the $4,000 to $6,000 estimate. On the other hand, a direct copy of a Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres odalisque by the Boston School artist William McGregor Paxton (1869-1941) was sold at the Boston auction house Grogan & Co. in 1994 for close to $20,000. “We had no clue it was going to sell for that much,” Michael Grogan, president of the auction house, said. “Someone in Texas bought it sight-unseen.”

Force has also sold artists’ copies of other artists’ works, such as Thomas Sully's (1857) Peasant Girl, based on Rembrandt’s Young Girl Leaning on a Windowsill (around 1645) and an Emma Peale Barton copy (around 1835) of Raphael’s Madonna della Seggiola (1514). She sold the Sully for $20,000, noting that “a good original Sully portrait would go for well over $100,000," and the Barton for $24,000.

One might guess that the audience for early works by artists who later gained renown would be relatively small, as so few of these pieces are recognisable. Alasdair Nichol, chairman of Freeman’s auction house in Philadelphia, who is an expert on the television program “Antiques Roadshow” once estimated a 1937 Clyfford Still early work in a Social Realist style for an auction value of $250,000 and an insurance value of $500,000. He speculates that an early Warhol might be of interest to "people who haven’t got the wherewithal to buy a ‘Marilyn’ and want it as a conversation piece,". Or it might hold interest to "completists who have other works by the artist and want something to round out their collection from his early years. A museum, for instance, like the Warhol Museum."

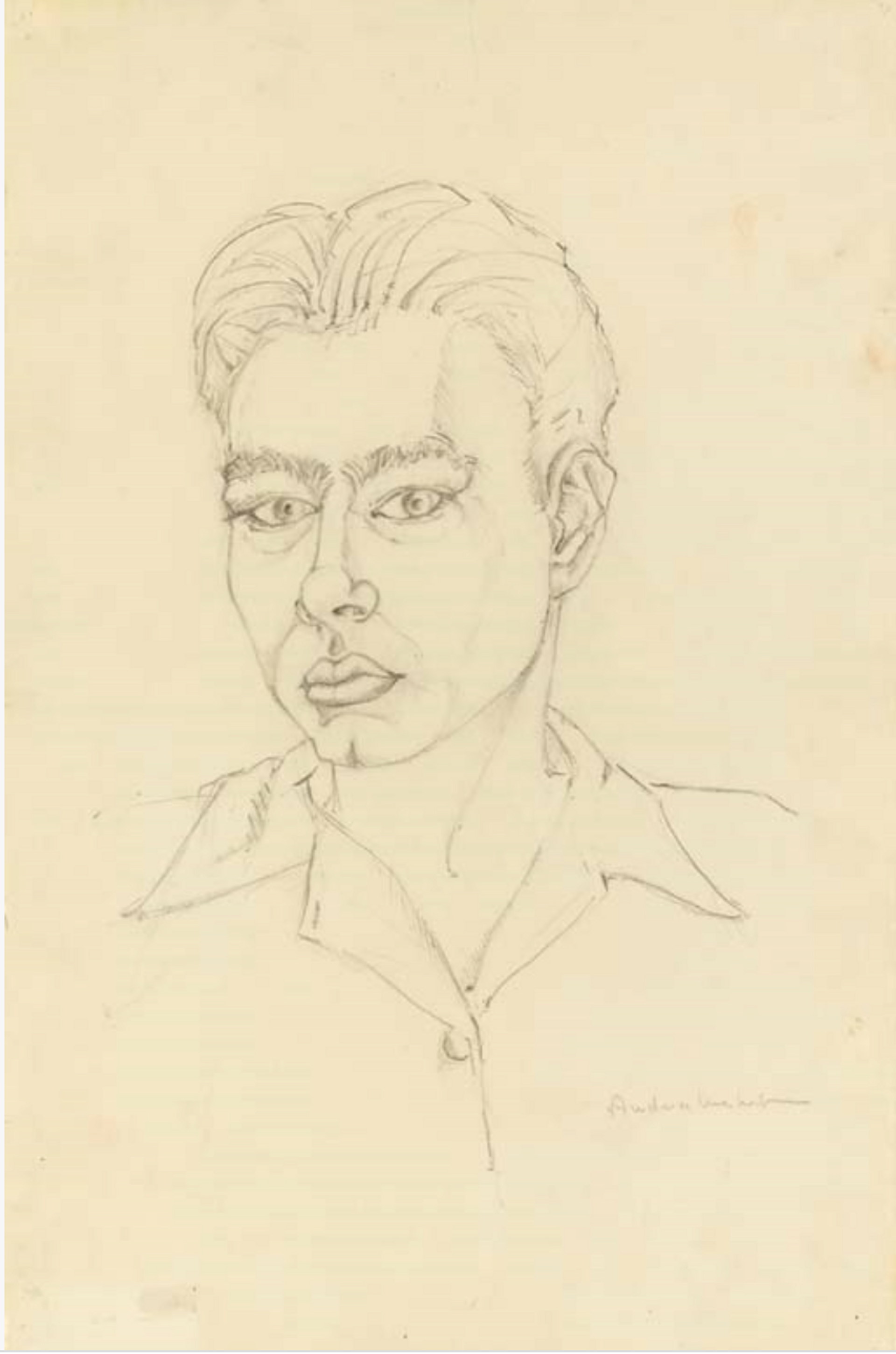

Andy Warhol, Self Portrait (1942). Courtesy of Christie's

However, Manley says that Nosepicker I and Living Room could attract a large group of prospective bidders, especially as, in the run-up to the 16 November sale Phillips has been "in touch with devoted Warhol collectors as well as collectors of American modernism, Social Realism and contemporary art".

The two early Warhol paintings are not the instances in which Manley has handled the artist’s work in his pre-Pop days. In 2003, when he was working as a deputy chairman at Christie’s, he brought to market an early self-portrait drawing by the artist that was dated 1942. That piece “sparked a bidding war, selling for $265,100 against an estimate of $100,000-150,000. Although that sale was nearly 20 years ago, Manley says next week's estimates are informed by its successful results.