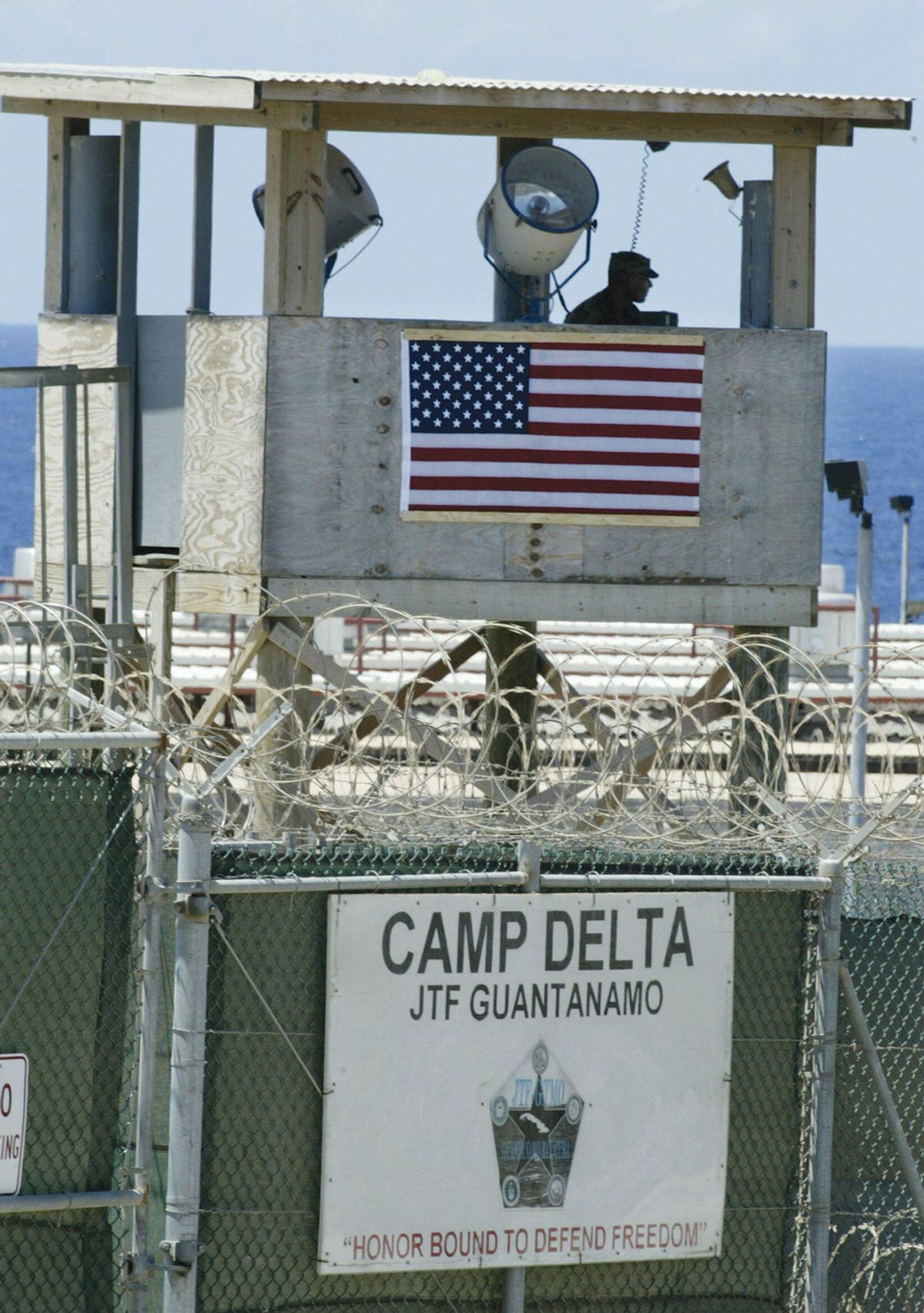

The travelling exhibition of 100 mostly drawings and paintings by eight suspected terrorists held for years by the US military at its base in Cuba, Art from Guantánamo Bay, raises a number of questions: is this an art show or a political message? Should we view people who may be criminals as artists? But perhaps the most pressing question the detainees, their attorneys and the Pentagon are grappling with is: who owns this art?

In 2009, the newly installed administration of Barack Obama decided to improve conditions for the hundreds of detainees rounded up in the Middle East as suspected terrorists and sent to Guantánamo Bay by, among other things, offering art classes. Detainees who were released, either due to lack of evidence of criminality or because they were deemed innocent, were permitted to take any works they created to their home countries. (The works were evaluated beforehand by intelligence officials at Guantánamo Bay for any hidden or coded messages before they were allowed out.)

In 2017, however, after the first Art from Guantánamo Bay exhibition took place at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, the US Department of Defense reversed its position and blocked the release of all works created by prisoners, regardless of whether or not military prosecutors believed their creators were associated with terrorism or anti-American acts.

Ownership a grey area

A Pentagon spokesman stated at the time that “items produced by detainees at Guantánamo Bay remain the property of the US government”. However, there has never been an official written statement with regard to the ownership of work created by Guantánamo prisoners or if and how it might be released.

The Pentagon during the Biden Administration has not made any noticeable change in this policy or loosened this ban, according to Beth Jacob, the founder and managing attorney for the Washington, DC-based nonprofit Healing and Recovery after Trauma, which represents men imprisoned at Guantánamo Bay. (Jacob represents two of the artists in the Art from Guantánamo Bay exhibition, Moath al-Alwi and Ahmed Badr Rabbani.) When she meets with her detainee-clients she takes notes of their discussions and intelligence staff at the facility review those notes to make sure that no classified or secret information is released. What is new since the summer of 2021, she says, is that “even copies of artworks by prisoners or descriptions of artworks can’t be taken out”.

Earlier this month, eight current and former Guantánamo detainees published a letter urging president Joseph Biden to reverse the Trump-era restriction on art leaving the complex.

Guantánamo Bay has held as many as 779 Middle Easterners suspected of terrorism since the prison opened in early 2002, and currently holds 36 men. Its history is “bizarrely unique” in terms of the rules governing its administration, says Erin Thompson, the professor of art crime at John Jay College and the curator of Art from Guantánamo Bay. There is no specific adherence to the laws that apply to prisons in the US, which often allow inmates to keep what they produce while incarcerated and after they are released, nor is there international law covering the designation of what the US military considers “enemy combatants”. “It is whatever law the government wants to apply,” Thompson says. “No rule concerning Guantánamo Bay is ever explained.”

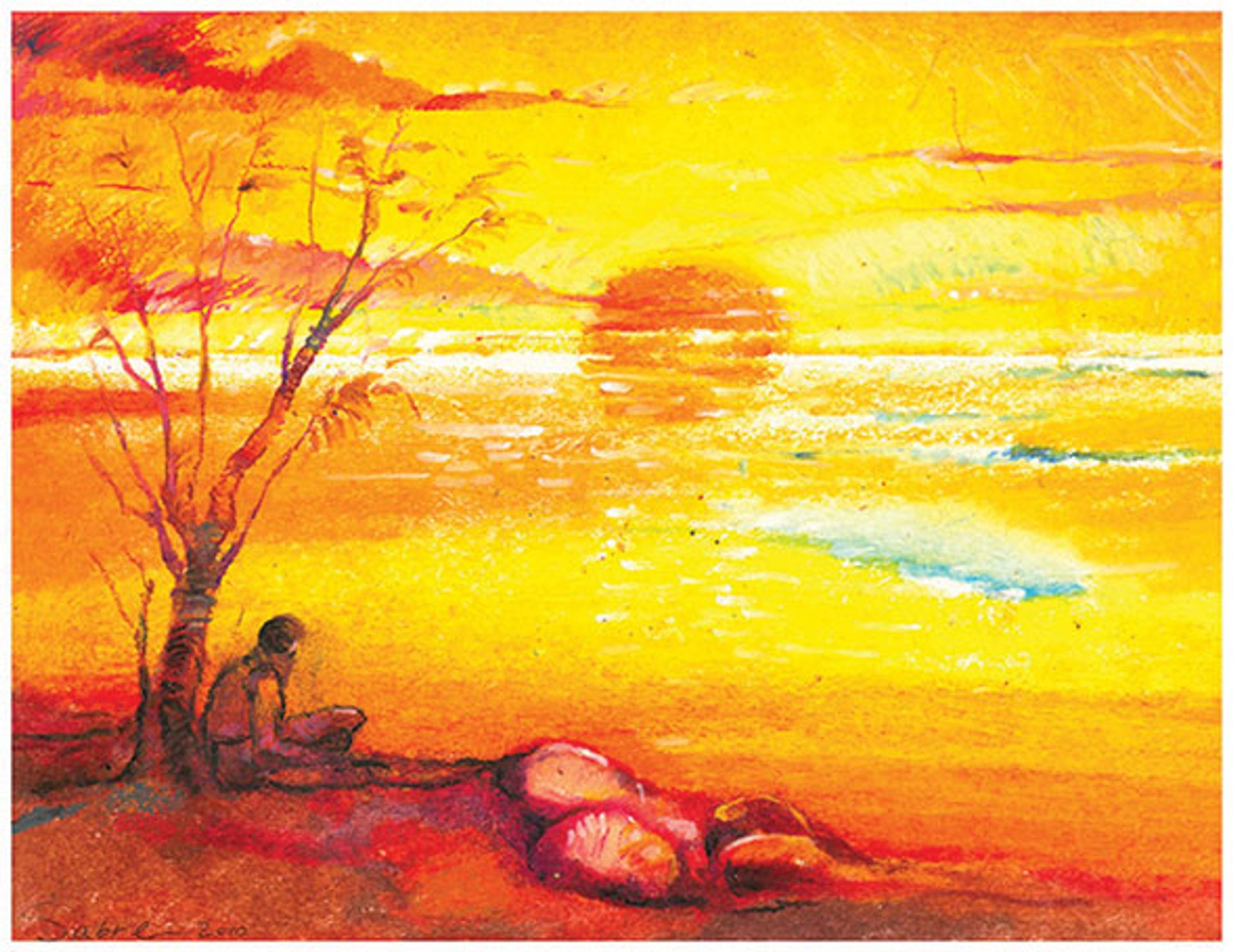

Untitled (Figure Looking at a Sunset, 2010) by Sabri Al Qurashi, who spent 12 years in Guantánamo Bay without charge Courtesy of the artist

Thompson believes that the Defense Department’s decision to forbid any works created by prisoners from leaving the prison compound, whether or not the individuals are released, directly stems from her exhibition at John Jay College, although the timing could just be coincidental.

“There are no secret messages to terrorists in these artworks,” Thompson says. “The message of this art is that the detainees are human beings and that they should be viewed as something other than criminals and terrorists.”

Reversal of fortune

Reversing efforts to reduce the number of detainees at Guantánamo Bay by both the George W. Bush and Obama administrations, the then president Donald Trump announced in early 2018 that “we are keeping [Guantánamo] open, and we’re going to load it up with some bad dudes”. He made no mention of the art produced by detainees but, as a practical matter, none of it has been allowed to leave the military prison when it is given to their lawyers or when individuals are released.

The Pentagon did not respond to requests for information about the policy of barring or allowing the release of art from Guantánamo Bay.

The question of whether or not the US government has a valid claim to the ownership of art created by Guantánamo prisoners has not been decided in any state, federal or international courtroom.

In some correctional facilities in the US, the rule is that “if the prison supplied the materials, such as paper and pens and whatever else, then they have a valid claim to owning the finished artwork”, says Viva R. Moffat, a professor of law at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law. “That’s why in many prisons, prisoners buy their own papers and pens so that what they create is their own personal property.” However, Moffat says that the Pentagon’s reasoning may be less based on an analysis of the law and more “from a position of power”.

The 100 drawings and paintings in Art from Guantánamo Bay represent only a small percentage of the total number of works created by those held in the facility. Thompson claims to have on her computer images of more than 2,000 works created by detainees at Guantánamo Bay since 2009.

“As soon as they got there, detainees were producing art, some of it just from boredom,” Thompson says. Before 2009, much of that art was in the form of images carved into the Styrofoam trays and plates on which detainees were given their food. After meals were consumed, the Styrofoam was collected and destroyed.

Under the Obama administration art teachers from multiple Gulf states, who worked as civilian contractors, were brought in to provide detainees with something to do. The detainees were permitted to use soft materials, such as crayons and pastels, as well as acrylic and watercolor paints in addition to brushes to create images. Even the occasional sculpture was allowed.

One of the eight artists in the travelling exhibition, Khalid Qasim, a Yemeni who was cleared for release in July 2022 after 15 years at Guantánamo, added coffee grounds, sand and gravel to water in order to stain the paper on which he was painting. He also produced sculptural objects from discarded materials, such as ready-to-eat meal boxes that he found lying around. Another Yemeni detained at Guantánamo for almost 15 years before being released to Oman in early 2017, Ghaleb Al-Bihani, painted images of boats (such as sailboats and dinghies), and even a lighthouse, that have a stronger New England flavour than one suggesting his home country.

Thompson notes that, while some detainees produced images that reflected their view of the US—for instance, one drawing showed the Statue of Liberty bound and gagged—or that revealed the harsh methods of interrogation that they underwent to show to their lawyers, a high percentage of the works were images of nature, such as landscapes and ocean scenes.

“They had seen a lot of ugliness and they wanted to look at beauty,” she says. Frequently, the images were of things they had never seen, such as ocean views (tarpaulins around the facility prevented detainees seeing the ocean around Guantánamo Bay) and snowcapped mountains, which they copied from photographs in copies of National Geographic magazines that were made available to them.

The pandemic paused the travels of the Art from Guantánamo Bay for a time, but this year it has made stops at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia and at Catamount Arts in St Johnsbury, Vermont. “I’m looking for the next venue right now,” Thompson says.