They are not exactly the lost monologues of Harpo Marx, but the publication of Lucian Freud’s letters will surprise many students of the famously reticent artist. He abhorred interviews and publicity and was more comfortable scrutinising other people than giving away anything about himself.

But the Freud-fest that accompanies the centenary of the artist’s birth this year includes the first publication of his collected correspondence. Love Lucian has been put together by his former assistant David Dawson and the art critic Martin Gayford, who wrote a book about sitting for Freud (Man With a Blue Scarf, 2010).

Full frontal Freud: a deep dive into the life and work of the raw, unflinching portraitist

Gayford tells The Art Newspaper that it was after he revisited his notebooks from that project that a book of letters became a possibility. “Looking through my notes I found that I had quite a bit more material. I was thinking it wouldn’t exactly be a memoir, more like extended biographical notes. I was talking to David [Dawson] about it four or five years ago, and he said somebody ought to do something about the letters; essentially the idea was David’s.”

But “doing something about the letters” proved a more daunting assignment than it sounds. For a start, where were they? When Gayford turned to what he hoped would be sure-fire sources of material, he more often than not drew a blank.

“Freud’s lover Lorna Wishart is said to have burned his letters. The letters to another girlfriend, Lady Caroline Blackwood, were lost in a house burglary in the 1990s, together with the letters of Robert Lowell, her husband. There are people that one would have expected him to write to such as Francis Bacon, but Bacon wasn’t a hoarder. Letters to the artist John Minton, perhaps? Well, there’s nothing in his effects,” Gayford says.

The artist in his studio in 1944, with his work The Painter’s Room on the easel

© Lucian Freud Archive

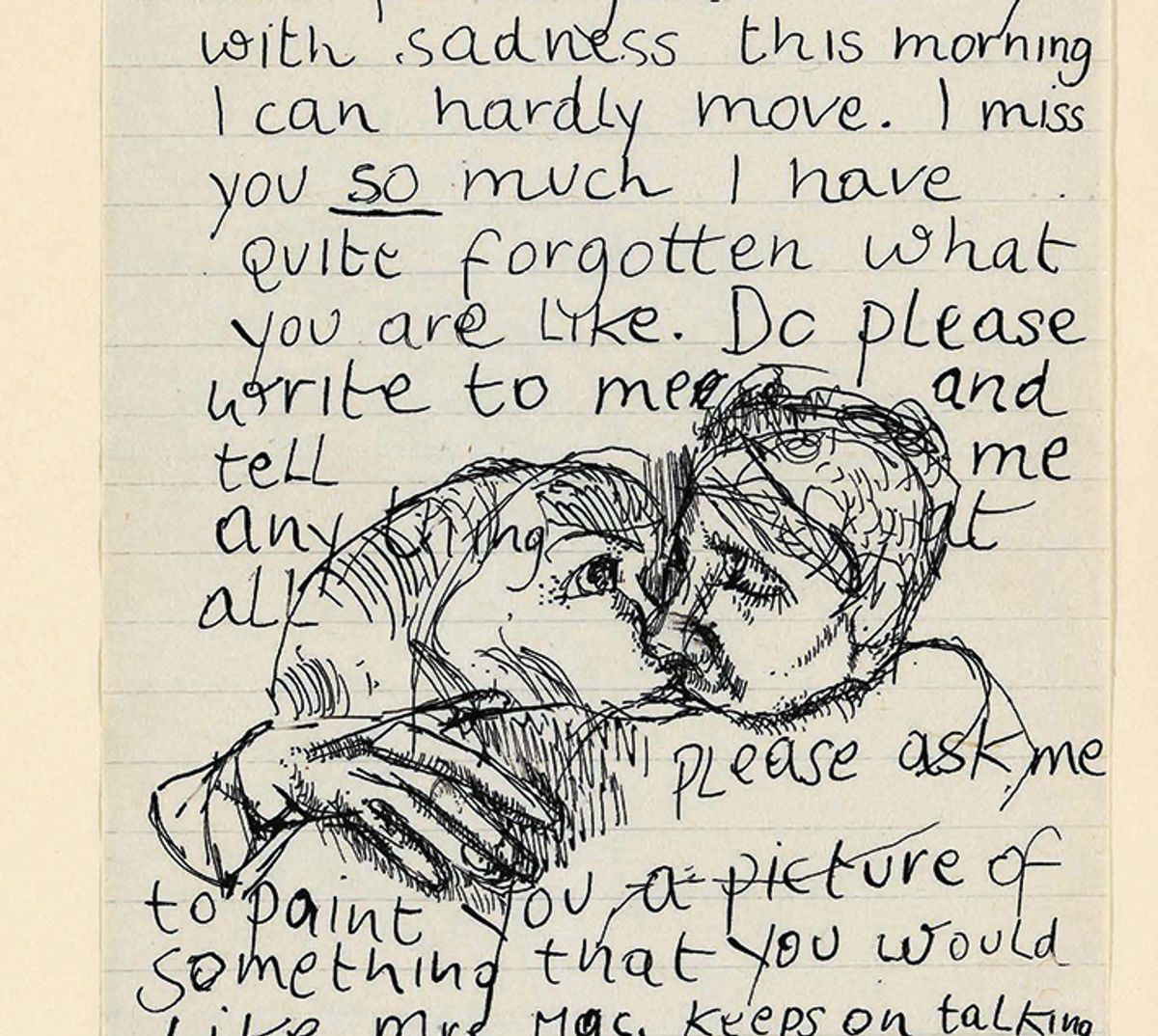

What’s more, the letters were hardly letters at all: they were postcards for the most part, scrawled in Freud’s childlike hand, complete with his lively misspellings. The book reproduces the cards recto and verso, as it were, alongside handy transcripts.

But Gayford had one particular pot of gold in his sights. “I had a feeling that I should pursue Craxton,” he says, referring to Freud’s friend and fellow artist John Craxton. “I got in touch with his biographer, Ian Collins, and that led to a fantastic box of letters.”

Most of the Craxton correspondence has never been seen before. The same is true of a drawing in black crayon of Craxton by Freud, Crax with Mustache [sic] (1946), which is reproduced in the book. Gayford adds: “I also came across a floorboard from the house where Craxton’s aunt lived in Abercorn Place, St John’s Wood, on which both artists painted.”

Despite the title of the new book, Freud rarely signed his letters with his first name. Sometimes he just put his initial. To his friends especially, the artist was known by a variety of nicknames. Gayford says: “There was endless wordplay. He was called things like ‘Peter the Hooch’, [perhaps after the Dutch Golden Age painter Pieter de Hooch], ‘Hooch’, ‘Spooch’.”

One of the charming features of Freud’s letters are the illustrations and doodles that accompany many of them. Writing to Blackwood, Freud included a sketch of the pair of them embracing, based on a photograph taken by Francis Bacon. “Lucian gave up the habit of drawing on his letters towards the end of the period covered by the book; in fact, the last one was on the letter to Blackwood,” Gayford says.

Gayford believes that the letters add to our knowledge of the artist. “Drafts of an anguished letter to Wishart reveal another side of him. He could be predatory and a cold fish, from what you read. But absurd as it may seem, he perceived himself to be a bit of a victim, and also a feminist.”

• Love Lucian: The Letters of Lucian Freud 1939-1954, David Dawson and Martin Gayford, Thames & Hudson, 392pp, £65 (hb)