Lucian Freud was not a plant lover. At least not in the sense of having “wellies and shovels and his watering can by the door,” says Giovanni Aloi, the curator of a new show at London’s Garden Museum about the artist’s pictures of plants. Although not typically green fingered, Freud did create a remarkable number of images of plants throughout his career, treating them more like he did his human subjects than traditional still-lifes. This side of Freud’s work was little explored until Aloi’s 2019 book, Lucian Freud Herbarium, on which this new show is based.

Potted plants surrounded the artist in his studio and often appear as supporting characters in some of his best-known portraits, whether it is a yucca tree in Interior at Paddington (1951) or a huge pelargonium in Large Interior W11 (after Watteau) (1981-83). But the Garden Museum, which will include 25 works as well as supporting material such as photographs and film, will focus on paintings where the plants are the main attraction and treated as subjects every bit as worthy, interesting and individual as the friends and family Freud painted.

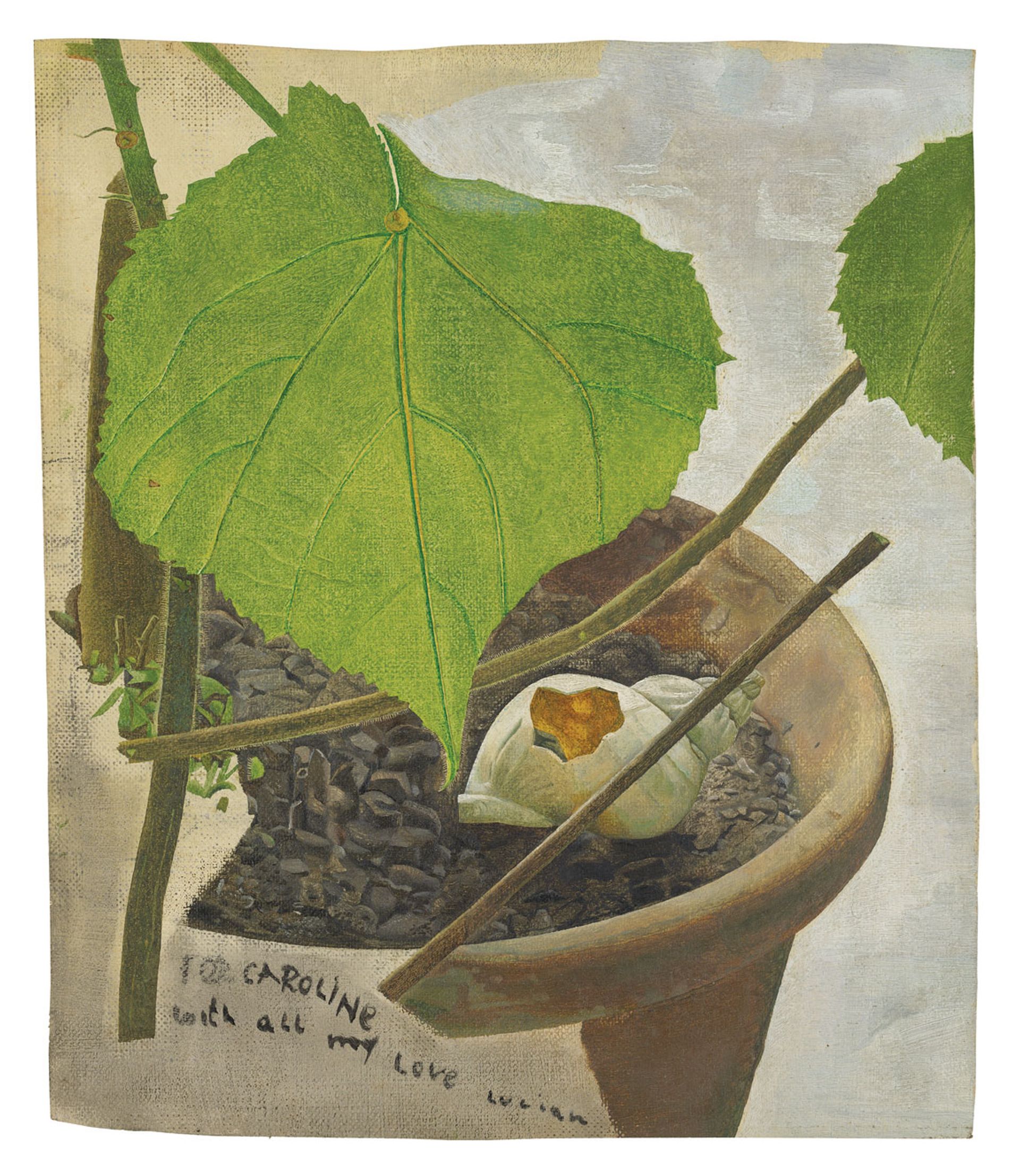

In fact, some of the plants in Freud’s possession were near enough part of the family, having been propagated from specimens owned by his grandfather, Sigmund Freud. One of the highlights of the show will be Still Life with Zimmerlinde (1950). The unfinished oil painting was first seen in public when it was sold by Freud’s second wife, Caroline Blackwood, at Christie’s in 2018. Zimmerlinde were fashionable with the Austrian middle classes at the beginning of the 20th century and this one is a descendant of a plant owned by Sigmund.

Freud's Still Life with Zimmerlinde (around 1950) Photo © Christie's Images/© The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022/Bridgeman Images

Cyclamens were the favourite flower of Lucian’s grandmother, Martha Freud, and of the artist himself. Freud’s assistant, David Dawson, has said that there were always cyclamens in the house; Freud liked the way their stems drooped as the flowers blossomed, which he captured in a neat 1964 oil painting, which is coming on loan from a private collection. Freud also painted a mural of cyclamens in a bathroom at Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, which will be recreated in the show.

The exhibition is purposefully titled Plant Portraits to highlight the way Freud employed a similar focus and thrust to flora as he did when painting people. “We’re trying to think about plants in ways that are not generic or grounded in science,” Aloi says. Instead, he wants us to try to think of them “like Freud did, as individual plants that you can have a relationship with”.

Aloi points out that plants today still suffer from the “marginalisation of nature” in place since the 15th century, which puts the natural world at the bottom of the painting hierarchy. Furthermore, “whenever we attach symbolism to a human body or an animal or a plant, we’re muting them,” Aloi says. In contrast, Freud “deliberately chose plants that don’t carry symbolism”.

Freud's Two Plants (1977-80) Tate © The Lucian Freud Archive

Plants are, on the face of it, better behaved sitters than people: they do not fidget, complain or need toilet breaks. Freud sometimes used them as a way to test light in his studio, as was the initial case with Two Plants (1977-80), which will be on loan from the Tate. But soon the painting took on a life of its subjects, an aspidistra and liquorice plant, began to change over time, which nearly drove him “around the bend”. Freud spent three years on the painting retaining the yellowing leaves and new growth that mark the passage of time in what became “lots of little portraits of leaves,” as he later described it to his biographer William Fever. “I wanted it to have a really biological feeling of things growing and fading and leaves coming up and others dying.”

Aloi hopes that visitors will not only appreciate this different side of Freud’s work, but also that the show will help enrich our own relationship with plants. He adds that many of the ones that Freud painted are still alive, looked after by Dawson at the artist’s former home and studio in London.

• Lucian Freud: Plant Portraits, Garden Museum, London, 14 October-5 March 2023