You might wonder if the long career of Frank Auerbach (born 1931) warrants yet further attention. After all, there has been a string of exhibitions and publications in recent years, including the retrospective of his work at Tate Britain (2015-16), a display of graphic work by Auerbach and Lucian Freud at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt (2018), and selected works at Luhring Augustine in New York (2020-21). Catherine Lampert, an art historian and one of Auerbach’s sitters for more than 35 years, published her intimate portrait of the artist’s life and work in 2015 (Thames & Hudson). William Feaver’s revised monograph has also just been published by Rizzoli. So what does Frank Auerbach: Drawings of People offer its readers that these other publications do not?

As its title indicates, this book concentrates on the artist’s drawings of people, a focus that has been fairly neglected until now. The book’s co-editor, Mark Hallett, the director of studies at the Paul Mellon Centre in London, suggests Auerbach’s portrait drawings are often “lost to view, crowded out” by a fairly relentless focus on the artist and his paintings. Hallett’s brief introduction provides context and a useful distillation of the best of relevant writing by Michael Podro, Robert Hughes and William Feaver. The five essays in the book move forward from this point, giving genuinely fresh critical perspectives. Contributions by Auerbach (who selected many of the images) and by Lampert are crucial.

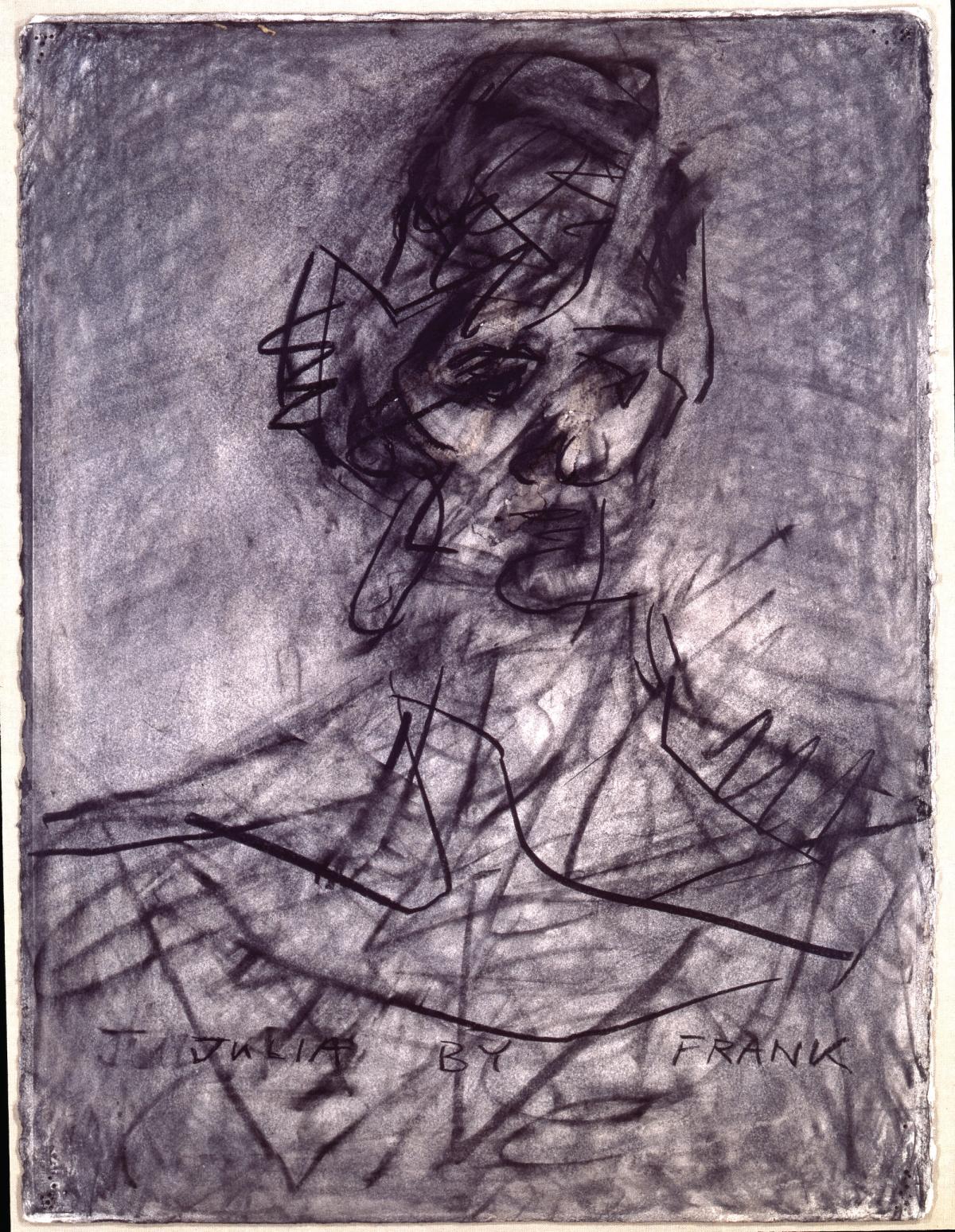

James Finch, assistant curator of the 19th and 20th centuries at Tate Britain, identifies the restlessness of Auerbach’s practice and his need to set impressions upon paper. Layers of drawing, rubbed out and redrawn, act as improvisatory attempts before a portrait is completed, one part of many.

I was unconvinced by Finch’s assertion of Auerbach’s legacy for artists such as Claudette Johnson and Michael Landy. More interesting is the connection he makes between Auerbach’s work and Erwin Panofsky’s definition of portraiture in Early Netherlandish Painting (1953)—ideas of individuality and totality—something that Auerbach’s intense working of portrait heads in an empty space helps him to achieve.

Filmic texture

David Alan Mellor, a professor at the University of Sussex, provides new contexts for Auerbach’s drawn portraits in the work of Charles Dickens, Walter Sickert, Antonin Artaud and the English artist Gerald Wilde. Mellor argues compellingly for the importance of film in Auerbach’s sphere of influence, including Lorenza Mazzetti’s Together (1956) and K (1954), as well as Auerbach’s fascination for music-hall culture and theatre, and the significance of images from commercial advertising.

Kate Aspinall’s essay focuses on the process of drawing for Auerbach. The independent art historian and artist identifies what she calls amassed and accrued drawings—essentially divided by the kind of labour deployed by the artist in each instance. What I appreciate most about this essay is Aspinall’s attendance to the fine detail of material process and fracture, mark and surface, scars and patches, peaks and pits. She notes: “While regarding Auerbach’s drawn portraits, we are suspended between certainty and dissolution,” a wonderfully lyrical summation.

The painter and writer Alexander Massouras’s interest is in Auerbach’s mimesis, and how the layers of his portrait drawings give them a durational quality that might be considered alongside other artists’ films, novels and paintings. Exploring the filmic qualities of Auerbach’s portrait drawings, Massouras makes some fruitful comparisons with the work of William Coldstream and he shows how both artists were concerned with the wholeness of the image. Massouras observes that “the subject is not just the sitter in his or her physical image, but that person’s encounter with Auerbach in the particular context of his studio”—perhaps the greatest contribution he makes to the discussion.

Barnaby Wright, deputy head of the Courtauld Gallery, focuses on the durational quality of Auerbach’s paintings and drawings, as all the authors do in one way or another, but in this instance through the unstinting commitment of his sitters. This is particularly important for Auerbach’s nine long-term sitters, where Wright sees lives unfolding and ageing over time in the drawn image. Wright notes the effort involved for model and artist, as well as Auerbach’s sensitivity to his subject’s mood.

As the volume’s various considerations of the durational quality of Auerbach’s portrait drawings arrive, in Wright’s essay, at the sitter, it is fitting that the “persistent sitter” (Auerbach’s term) has the last word. Catherine Lampert’s afterthoughts are delightfully evocative. In something of a closing statement, she asserts: “The wonder of occupying space and the goal of bringing all of life to the canvas is as enticing as ever.” It is the vitality of life over time and the ongoing role of the relationship between artist and model in Auerbach’s portrait drawings that this book deals with so well.

• Mark Hallet and Catherine Lampert (eds), Frank Auerbach: Drawings of People, Paul Mellon Center/Yale, 336pp, 200 illustrations, £40/$50 (hb), published 23 October (UK), 29 November (US)

• Beth Williamson is an art historian and writer specialising in the history and theory of 20th-century art in Britain