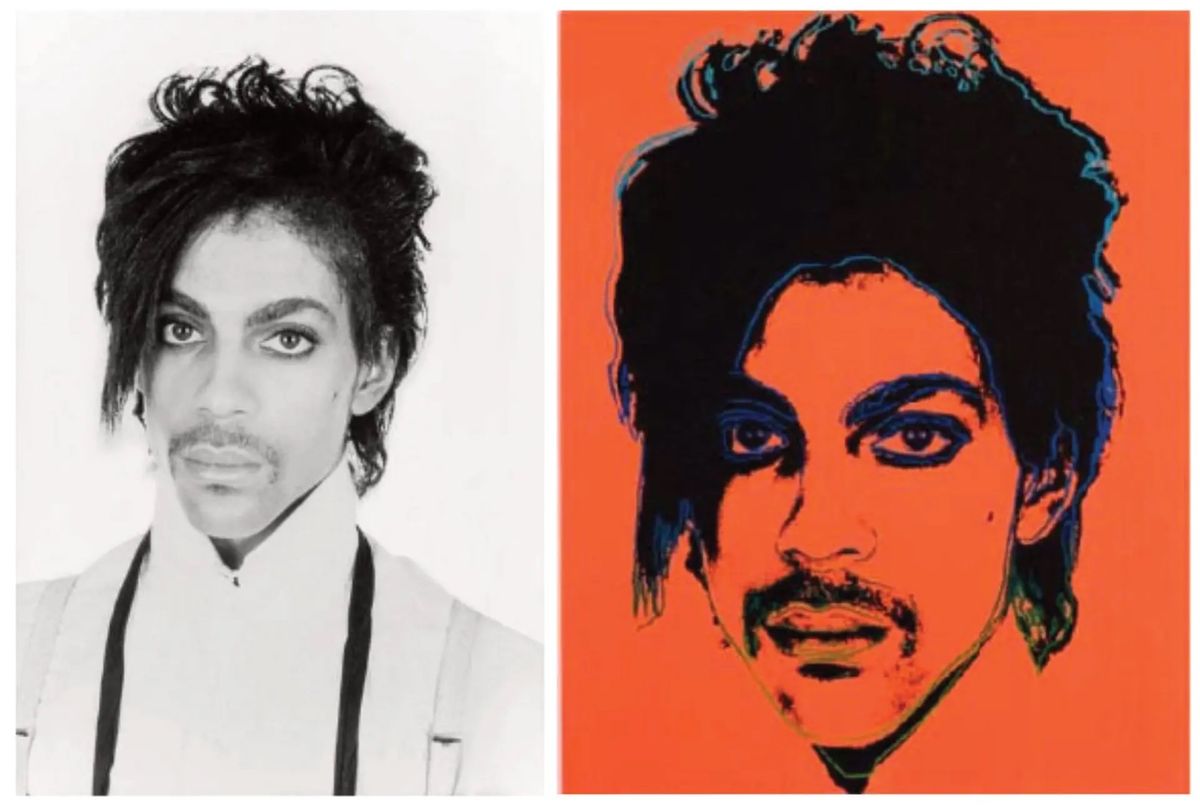

In oral arguments today (12 October), justices at the US Supreme Court pointedly questioned a claim that a lower appeals court wrongly discounted a “changed meaning or message” test in a copyright infringement case. The issue is of high stakes to photographers and others who license creative works, and artists who appropriate or re-work existing imagery. It pits the renowned music photographer Lynn Goldsmith against the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Goldsmith says the foundation had no right to earn a license fee in 2016 from Condé Nast magazine for use of a silkscreen print Andy Warhol created, which he based on her copyrighted photograph of the musician Prince.

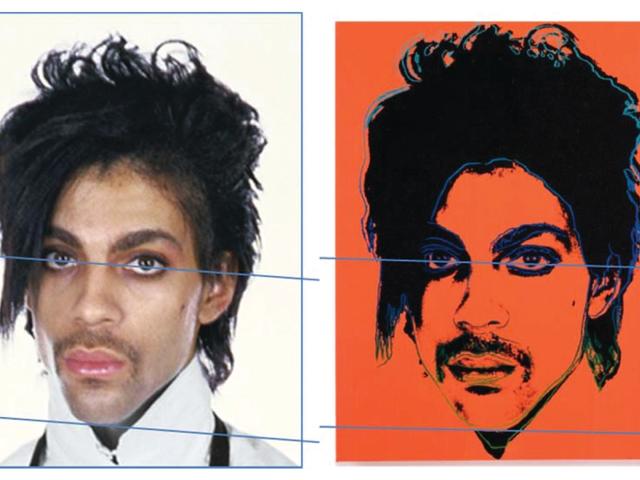

The foundation has asked the Court to overturn a 2021 decision by the Second Circuit federal appeals court, which denied a “fair use” defense for the images Warhol created based on Goldsmith’s photo, which he was provided under a one-time-use license that Goldsmith granted to Vanity Fair magazine in 1984. The appeals court said Warhol’s Prince works failed all of the required fair use tests needed to defeat an infringement claim, including the “purpose and character” or so-called “transformative” test, which examines whether the second work adequately transformed the first. Warhol’s works recognizably derived from and kept essential elements of Goldsmith’s portrait, adding no more than “the imposition of [Warhol’s] style”, the appeals court said, rejecting the foundation’s claims regarding the importance of Warhol’s changed meaning or message.

Roman Martinez, a lawyer for the foundation, told the Supreme Court justices that Goldsmith’s view “banishes transformative meaning from the equation altogether”, violating law and precedent and undermining the key goal of copyright, which is “promoting creativity for the public good”. He said a ruling for Goldsmith would make it “illegal for artists, museums, galleries and collectors” to display, sell and profit from a large number of works.

But several justices quickly collided with the foundation’s views. Justice Sonia Sotomayor pointed to the “purpose” test and compared the uses to which the two competing works were put. Goldsmith’s licensed photo “was a highly commercial use. Goldsmith also licensed her work to magazines, just as Warhol’s estate did. So how is it that your [2016] license and Goldsmith’s photographs do not share the same commercial purpose?” She said the foundation had argued that transformation “standing alone” satisfied the “purpose and character” test, but “I don’t see how that can be”.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh said it seemed “classic” that photographs such as Goldsmith’s would be used in media stories about the photo subject, and therefore “competing in the same market”—magazine stories about Prince. But Martinez sought to narrow the justices’ examination of “purpose” away from the “level of generality” of magazines or portraits, saying that the meaning of the licensed Warhol image was “the dehumanising effects of celebrity” on Prince.

Justice Samuel Alito asked how a court is to determine “the message or meaning of works of art”, adding that “there can be a lot of dispute” about meaning or message.

Lisa Blatt, a lawyer for Goldsmith, argued that to earn the fair use defense, a copier “has to explain why it is needed” to use the prior artist’s work. Here, the foundation has “never given any reason” for copying Goldsmith’s picture to be able to commercially license Warhol’s image, she said. The foundation responds that "Warhol was a creative genius who imbued other people’s art with his own distinctive style. But Spielberg did the same for films and Jimi Hendrix for music. Those giants still needed licenses. Even Warhol followed the rules. When he did not take a picture himself, he paid the photographer.” The foundation “failed to do so here”, she said, and instead it maintained that “adding new meaning is a good enough reason to copy for free”.

Yaira Dubin, Assistant to the US Solicitor General, argued the views of the US government, which filed a friend of the court brief because of its interest in US copyright matters. The brief supported Goldsmith. The Warhol Foundation has never tried to show, Dubin said, that copying the creative elements of Goldmith’s photograph “was essential to accomplish a distinct purpose”. She added that “the foundation commercially licensed Warhol’s Prince to serve the same purpose as the original, depicting Prince in an article about Prince. Using another artist’s work as a starting point to turn around and compete directly with their original has never been considered fair.” Instead, the foundation is suggesting it is fair, she said, “by urging you to look primarily to what the silkscreens mean, rather than why the copying was justified. The court should reject that test,” she said, which “requires courts to inquire into the meaning of art” and would “destabilise longstanding industry licensing practices that promote the creation of original works”. Sequels and other adaptations would “become fair game if conveying a different meaning confers licence to copy”.

At the close of the arguments, justices Kavanaugh and Ketanji Brown Jackson appeared to be working with Dubin to craft the best language for the court’s decision if it ends up agreeing with the government. Dubin suggested that the court could say that if a copier wants to be able to use the fair use defense when incorporating an existing work, the person copying must show that using the first work was “necessary or at least useful” in order “to achieve a distinct purpose”.

The parties now await a decision.