This autumn, the US Supreme Court will consider whether you—artists, collectors, gallerists, historians, critics, curators, museum administrators, educators—all of us as producers, stewards and the audience for art, are relevant. Does your opinion of the significance of a work of art have legal value? Does your ability to discern meaningful difference between two visually similar works matter?

These questions are at the true centre of the dispute between the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, which holds copyrights in art created by Andy Warhol, and Lynn Goldsmith, a photographer who is probably best known for her portraits of celebrities.

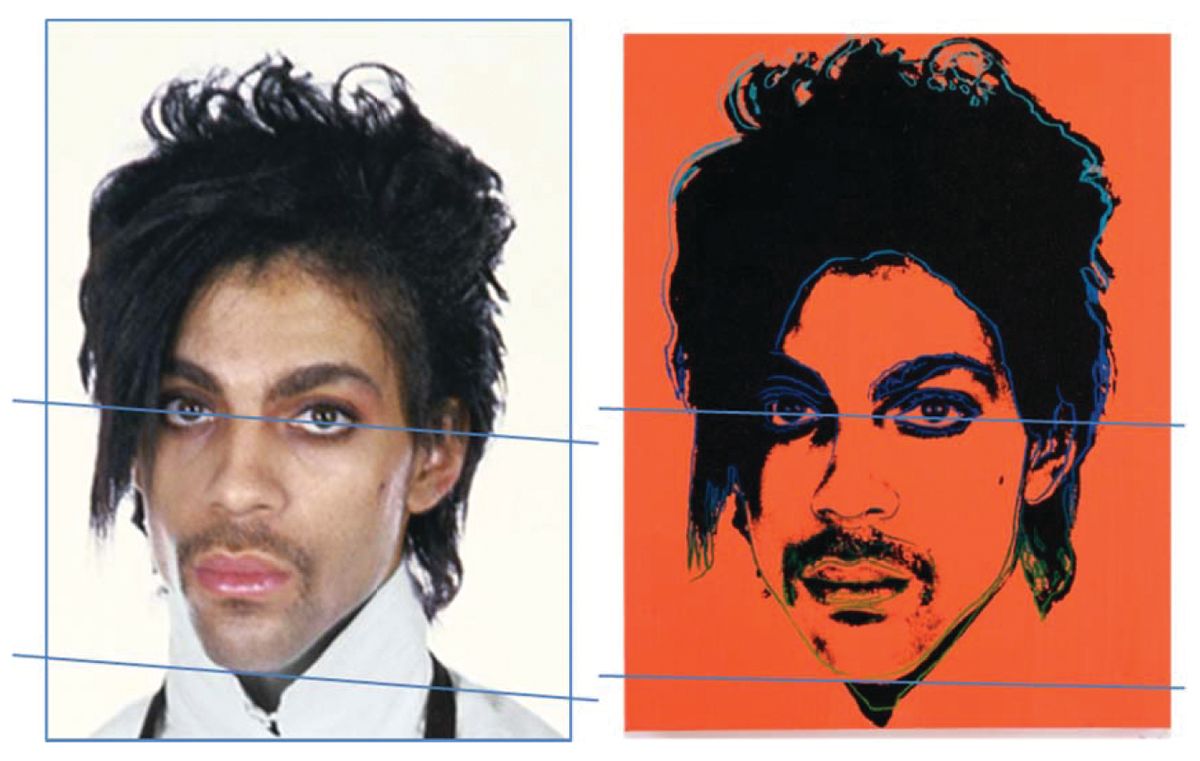

The dispute was triggered by Goldsmith’s objection to Warhol’s use of her photograph of Prince as a source for his 1984 silkscreen print series. When Condé Nast used one of Warhol’s images on the cover of a Prince tribute magazine in 2016, Goldsmith asserted that her rights in her image had been infringed. Anyone could see that Warhol had used her photo as a source, she reasoned, and so, she claimed, he should have asked permission and she should be paid.

The foundation responded by asking the appropriate New York district court to affirm that Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s image was fair, requiring no permission and no fee, because the resulting work had a new meaning and message. This is the “transformative use” standard set by the Supreme Court in 1994 and applied many times since across the nation. The district court agreed with the foundation, and some of us thought that was that.

Then things took a turn, ultimately leading to the Supreme Court’s rare decision to hear a case focusing on visual art. On appeal, the Second Circuit came up with an unprecedented rule that it applied to find that Warhol’s works are infringing—even though the court conceded that the meaning and message of the works are distinct from Goldsmith’s.

The Second Circuit stated that courts should not “seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue”. Instead, the court fixated on the question of visual similarity and decided that because Warhol and Goldmith’s images serve the same function—both were “created as works of visual art” and are “portraits of the same person”—Warhol’s work is infringing because it is “recognisably deriving from, and retaining the essential elements of, its source material”. In other words, unless its visual relation to another art source is sufficiently obscured, the follow-on work is infringing.

It is important to understand the practical implications of this: if a judge cannot look past the visual similarity between two works and decide that the difference between them matters, then you have no input. No matter how expert, your opinion on the cultural or historical significance of an allegedly infringing work is irrelevant. You do not have a voice here, despite your connoisseurship, your scholarship, your various investments in art or your interest in a creative ecosystem that can allow a Warhol to develop—or a Hans Haacke, Renée Green, Dara Birnbaum, Adrian Piper, Arthur Jafa or Alfredo Jaar, for example.

This should disturb everyone. The history of art includes many works that are visually similar. If our ability to see meaningful differences between them is dismissed by the law, the results are so bizarre that we have not been able to take them seriously—yet.

If the Supreme Court does not reaffirm its own transformative fair use standard, it is not too far a stretch to say that our greatest public and private collections, not to mention many studios, galleries, textbooks and Instagram accounts, will suddenly be filled with unlawful art. US legal jurisdiction will not confine the repercussions.

It is also important to highlight the insidious nature of copyright overreach. No one is arguing that creatives should not be reasonably paid, but there is too great a cost to the default “always-on” licensing scheme envisioned here. The Supreme Court has repeatedly made clear that copyright does not trump free speech. Asserting rights beyond those granted by the copyright law is nothing short of an attempt to suppress freedom of expression. Warhol’s Prince is not Goldsmith’s Prince. Period.

As part of the Warhol Foundation’s petition for a hearing, several “friends of the court” briefs were filed by groups of copyright and art law professors, two prominent artists and art professors, and the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation and Roy Lichtenstein Foundation joined by the Brooklyn Museum. As briefing for the Supreme Court hearing nears completion, all of us—and especially US cultural institutions, their donors, patrons and those who sit on their boards—must appreciate that it is time to speak up.

• Virginia Rutledge is an art historian and lawyer. She co-authored the amicus brief in Cariou v. Prince, submitted in 2013 by the Warhol and Rauschenberg foundations, and endorsed by 29 major visual arts organisations across the US