For Americans buying art and other cultural property in the UK and Europe in the not-quite-finished-pandemic, post-Brexit, current high-inflation and strengthening-dollar era, the task of purchasing pieces and shipping them back home has become more complicated and frequently more expensive, and the length of time that it takes to finally receive items has lengthened significantly, according to numerous US art advisers and lawyers representing these collectors.

There has been some good news for US buyers, as the relative strength of the dollar makes purchases less expensive, according to Clare McAndrew, the founder of Arts Economics, a Dublin-based research and consulting firm, and thereby more attractive. “The very strong dollar now would be a benefit for collectors,” she says. The value of the euro against the US dollar has been falling through most of 2022, with one dollar currently nearly equal to one euro, a decline of 14% since January. At present, the pound is worth $1.13, an almost 18% drop in value since the beginning of the year.

Unwelcome surprise

Of course, for US collectors seeking to sell abroad, the reverse is true. Paul Hewitt, the director general of the Society of London Art Dealers, says that “on the currency issue, what I hear is that the weakness of the British pound versus the American dollar has made the UK a less attractive location for US collectors to sell works of art, particularly at public auction”. He adds that while saying “the current weakness of the pound is driven by Brexit is too simplistic, it certainly is a contributing factor”.

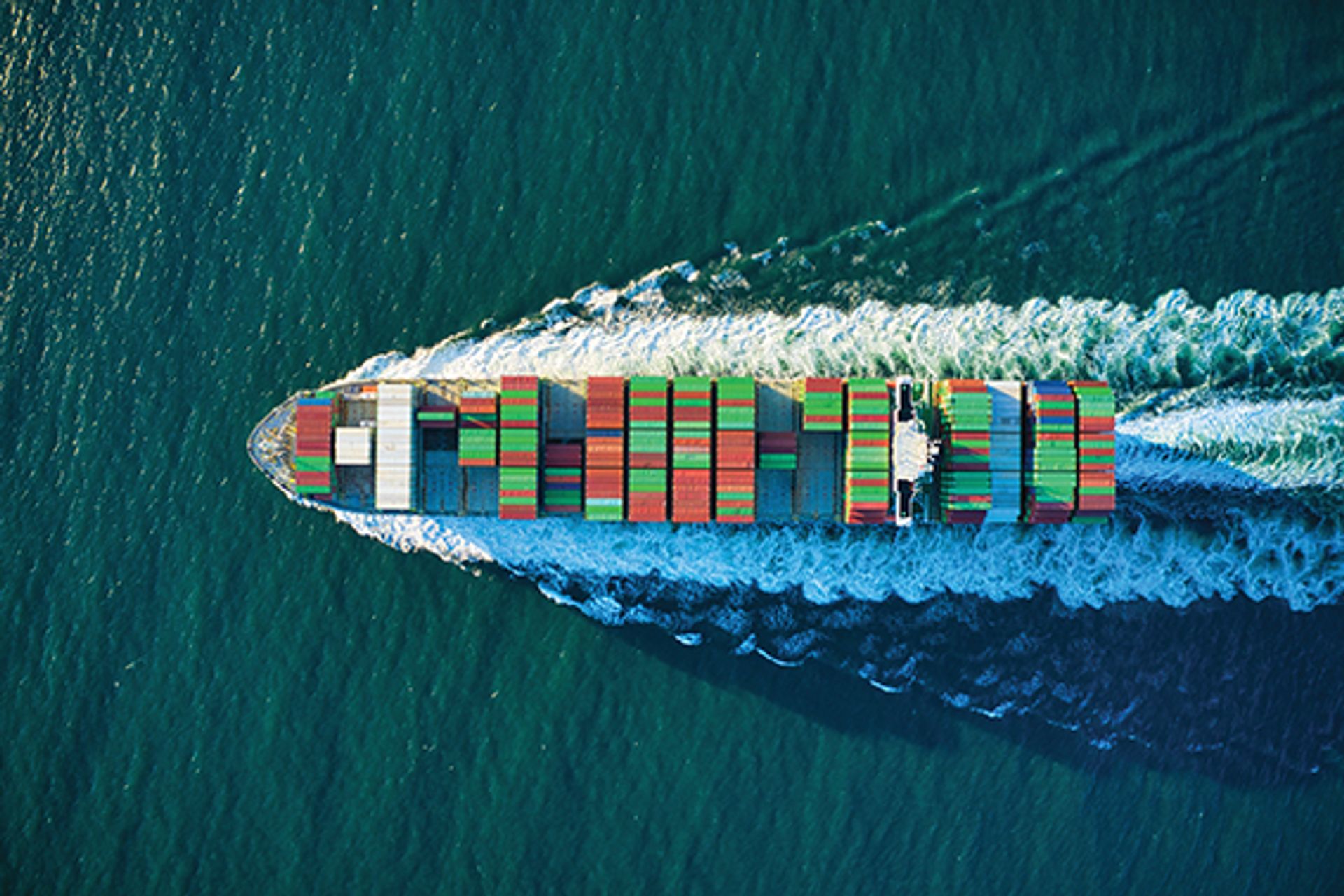

The cost of crating and shipping art around the world has increased significantly post-pandemic, thanks to higher labour, wood and fuel bills; meanwhile, post-pandemic supply-chain issues continue to cause delays Venti Views/Unsplash

Hewitt notes that dealers registered in the UK have been required of late to undertake additional due-diligence checks on buyers and sellers of higher priced works of art in the face of concerns about money laundering and looting. Additionally, “global supply-chain issues and the increased cost of freight triggered by the pandemic is making the cost, time required and general effort of exporting works of art to the US greater than before”.

Much of this has come as an unwelcome surprise to US buyers for whom the lower relative prices of objects purchased in Europe are offset by delays and higher costs of shipping. “To give one example, we have a client who began trying to export a group of 19th-century objects from the UK to the US in early 2021,” says Jennifer Morris, a lawyer who heads the art and museum law practice at the Richmond, Virginia-based office of the Cultural Heritage Partners law firm. The client, she adds, is a private collector and not a dealer, and the cumulative price of the various pieces is considerably under $1m. “The objects, last I heard, have still not arrived in the US.”

The problems have been numerous. The individual objects the client had purchased have needed to be identified in person, a process that was delayed by experts working from home without access to their equipment and files. Then, there is the backlog of customs paperwork, much of which can only be filed in hard copy, as well as additional fees for climate-controlled storage while the process runs its course. That client, Morris notes, has become “frustrated enough that he has contemplated giving up on the whole thing”.

Frustrations are being felt by many exporting from mainland Europe as well, although the waiting time is longer for some than for others. Elizabeth Fiore, an art adviser in Manhattan, says she purchased two Louise Nevelson sculptures for a client from a gallery in Italy in March “and it took four months to receive the export licence”. She adds that “typical turnaround time for an export licence pre-pandemic was a couple of weeks”.

“The pandemic has slowed down everything,” says Leila Amineddoleh, a New York City art lawyer, “due to a backlog of requests for export and customs clearance.” The process has also become bogged down as a result of new scrutiny in the UK and Europe over the use of art by criminals engaged in money laundering, looted property (Holocaust-related and otherwise) and national claims of patrimony. “More countries are saying about art and other cultural property, ‘this really should belong to us,’ and a lot of items are getting trapped in the bureaucracy,” art lawyer Susan Duke Biederman says. The UK “is blocking stuff from leaving, and it can be for years”. And, throughout the lengthy process, whatever the outcome, the buyer must pay for legal assistance and climate-controlled storage.

Delays have also resulted from the costs of crating and shipping, which have increased due to the rising prices for wood, labour and fuel, Manhattan art adviser Todd Levin says. “Right after Covid hit, a lot of things got shut down,” he says, “and they have been coming back slowly.”

The British government’s withdrawal of the VAT Retail Export Scheme from 1 January 2021 has piled additional costs on top of the delay. This element eliminated the ability of people living outside of the UK, such as US tourists, from receiving a refund of the 20% value-added tax when they brought items purchased in the UK (Northern Ireland is excluded) home with them. Before Brexit—the formal withdrawal of the UK from the European Union—the VAT could have been reclaimed in its entirety. “Such a high tax burden greatly discourages US collectors from buying art from the UK,” says Robert Darwell, a partner in the New York-based law firm, Sheppard Mullin.

The most common solution to that problem is having objects shipped directly to the buyer’s home by the British gallery or auction house where they were purchased, as the seller can arrange for the VAT to be waived.

Buyer beware

Certainly, buying art in one or another country may come with surprising fees and expenses, particularly for US citizens who are accustomed to paying only a work’s (negotiated) price and sales tax back home. In Great Britain there is the 20% VAT, in addition to the resale royalty (payable by the buyer).

And it is not only the novice art buyer making purchases at foreign fairs who has been surprised by the changes. One of the effects of the pandemic has been to move a growing percentage of the viewing and purchasing of artworks from in-person transactions to the online realm. “The art world’s footprint has always been a global one, but during the first year of the pandemic in particular collectors became increasingly accustomed to looking at art via high-resolution images embedded in PDFs and in a kind of geographically detached outer space otherwise known as online view rooms,” says New York City art advisor Irene C. Papanestor. “When purchasing work online, many tend to overlook where the artwork is actually located and the associated transportation costs needed to get the artwork into their homes or storage facilities.”

For first-time buyers and experienced collector alike, the experience of getting works purchased at distant fairs and in virtual rooms has proven to be increasingly complex—even when the exchange rate is to their advantage.