The photographer, filmmaker and fearless multi-disciplinary artist William Klein died on 10 September at his home in Paris. He was 96. His death was confirmed by Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York, which represents him (and where his photographs taken in Africa in the 1960s are currently on view, until 17 September). Klein was best known for his photography, which encompassed and intertwined a wide array of subjects including candid street photography, kinetic fashion shoots and high-contrast abstract work. He also maintained robust filmmaking and painting practices.

Klein was born in New York City in 1926, and lived there until 1946, when he was deployed to Europe as part of an Allied forces effort to assist with reconstruction following the Second World War. He obtained his first camera—which he won in a card game—during this trip, and eventually settled in Paris, where he studied painting and sculpture at the Sorbonne and worked in the studio of the renowned Modernist painter Fernand Léger. It was in Europe that Klein began to seriously pursue his great love, photography, and he soon started transposing the abstract forms of his paintings and sculptural studies to shadowy, geometric photographs of objects in motion, as seen in compositions such as 1952’s Moving Diamonds, Mural Project, Paris or Turning Black Egg.

William Klein, Untitled (Moving Diamonds on Yellow), around 1952. © William Klein, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

“Photography was a way out of the ABCs of abstract painting from that period in Paris,” Klein told Interview magazine in 2013. “I discovered that I could do whatever I wanted with a negative in a darkroom and an enlarger.”

Klein’s experimentation soon won him a fan back in his hometown: Alexander Lieberman, an art director at Vogue, who helped bring Klein’s kineticism to the glossy realm of high fashion. Klein found inspiration in the brash, busy chaos of the New York streets where he spent his youth, and would spend days wandering the city, taking photographs of strangers and talking with them about their lives, as immortalised in his iconic 1956 photobook Life is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels. He soon began to shoot his editorials on the street, too, placing models amid crowds and taxicabs and photographing them in striking, quasi-surreal scenes of clutter and poise. In an age still dominated by the stylised studio shoots of photographers like Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, Klein’s decision to bring fashion photography down to the bustling friction of the street was revolutionary.

William Klein, Antonia and Yellow Taxi, New York, 1962. © William Klein, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

His pursuit of images was not limited to photography. By the 1960s, Klein had begun to make films on the recommendation of his friends Chris Marker and Alain Resnais, icons of Paris’s Left Bank. His first film, Broadway by Light (1958), exemplifies the sort of dizzying loudness that Klein loved about New York, and which he captured so well in his photos.

“The first thing that people photograph or digest in New York is Broadway and Times Square—it’s the most beautiful thing in New York, and in America,” Klein said of the film in an interview with Aperture. “But what is it, what are people actually seeing? They are seeing the spectacle of advertising; it’s buy this, buy that. It’s beautiful, but it’s made up of sales pitches, and people are fascinated and seduced by advertising.” His desire to capture life as it really occurred would persist throughout his films as they grew to encompass subjects such as Eldridge Cleaver’s flight from America and the 1981 French Open tennis tournament.

William Klein, Moves and Pepsi, Harlem, New York, 1955. © William Klein, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

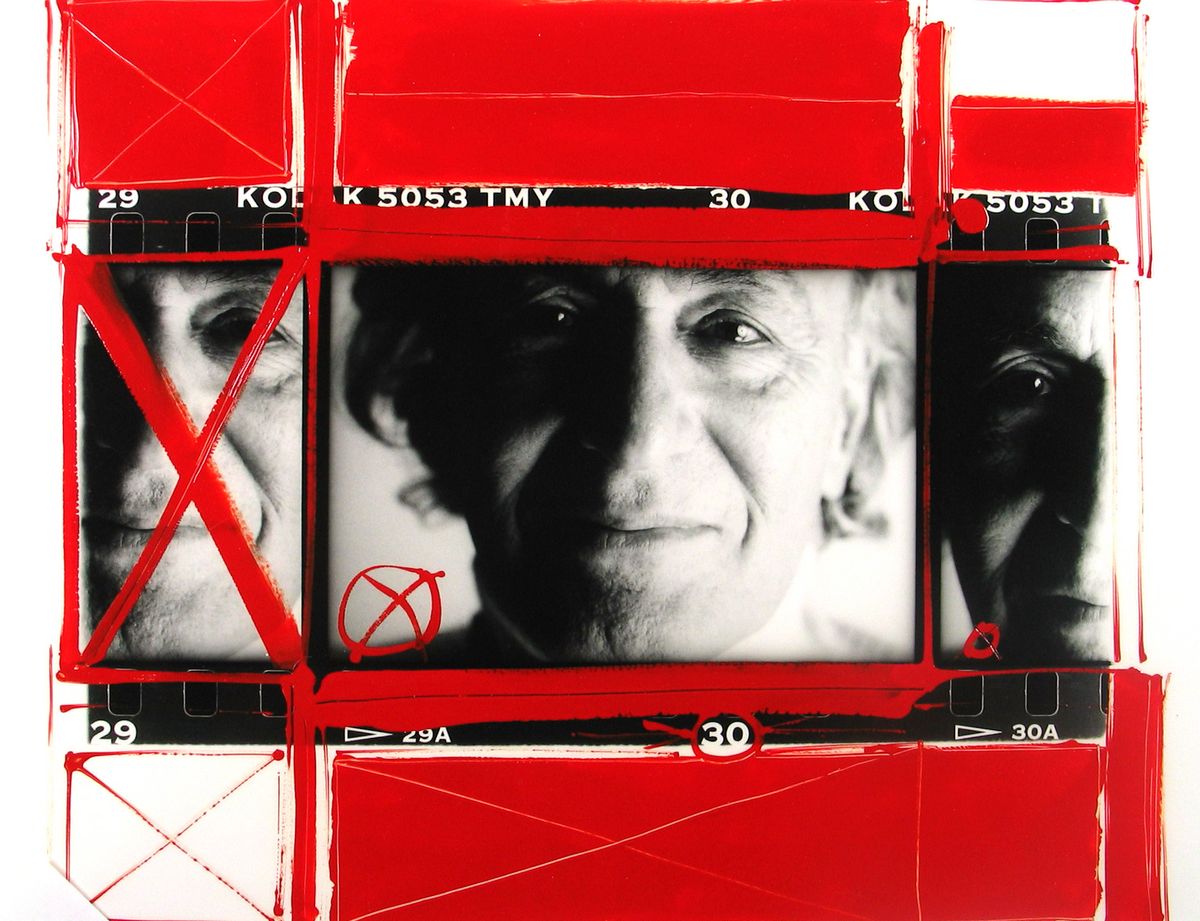

Klein’s wide-ranging talents won him acclaim in the worlds of fashion, film and fine art, and he received numerous honours including the Medal of the Century from the Royal Photographic Society in London in 1999 and the International Center of Photography’s Infinity Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2007, as well as countless museum exhibitions and acquisitions. (A major exhibition of his work at the International Center of Photography that was scheduled to close on 12 September has been extended until 15 September.) Despite his accomplishments across so many media, Klein always returned to photography and remained an active photographer well into his later years.

“I have a special relationship with God,” Klein told Interview of his approach to his favoured discipline. “And when I take the right photograph, God gives me a little bing! in the camera. And then I know I’m on the right track.”