Carolee Schneemann (1939-2019) is best known for her political, erotically charged performances, which initiated the interdisciplinary works of the feminist art movement. “Not only am I an image-maker,” Schneemann said in 1963, “but I explore the image values of flesh as material I choose to work with.”

A year later, aged 25, she orchestrated Meat Joy (1964), its messy mix of bodies spread across the stage covered in paint, paper, cellophane and—most famously—raw meat. It was one of the first works in her new style and the product of a new idea: kinetic theatre. Participants moved to a soundtrack of collaged pop music and street recordings so that the songs’ popular cultural codes for sex combined with the intimate dressing and undressing exchanges.

The work had an immediate impact—one audience member was driven so wild he tried to strangle Schneemann midway through—and has continued to exert its influence through Schneemann’s film documentary, as well as grainy photographs taken by Robert McElroy. Meat Joy will be one of the star pieces in Carolee Schneemann: Body Politics, at the Barbican Art Gallery. The first UK survey of the artist will include more than 300 works, ranging from early paintings and sculptural assemblages to films and installations.

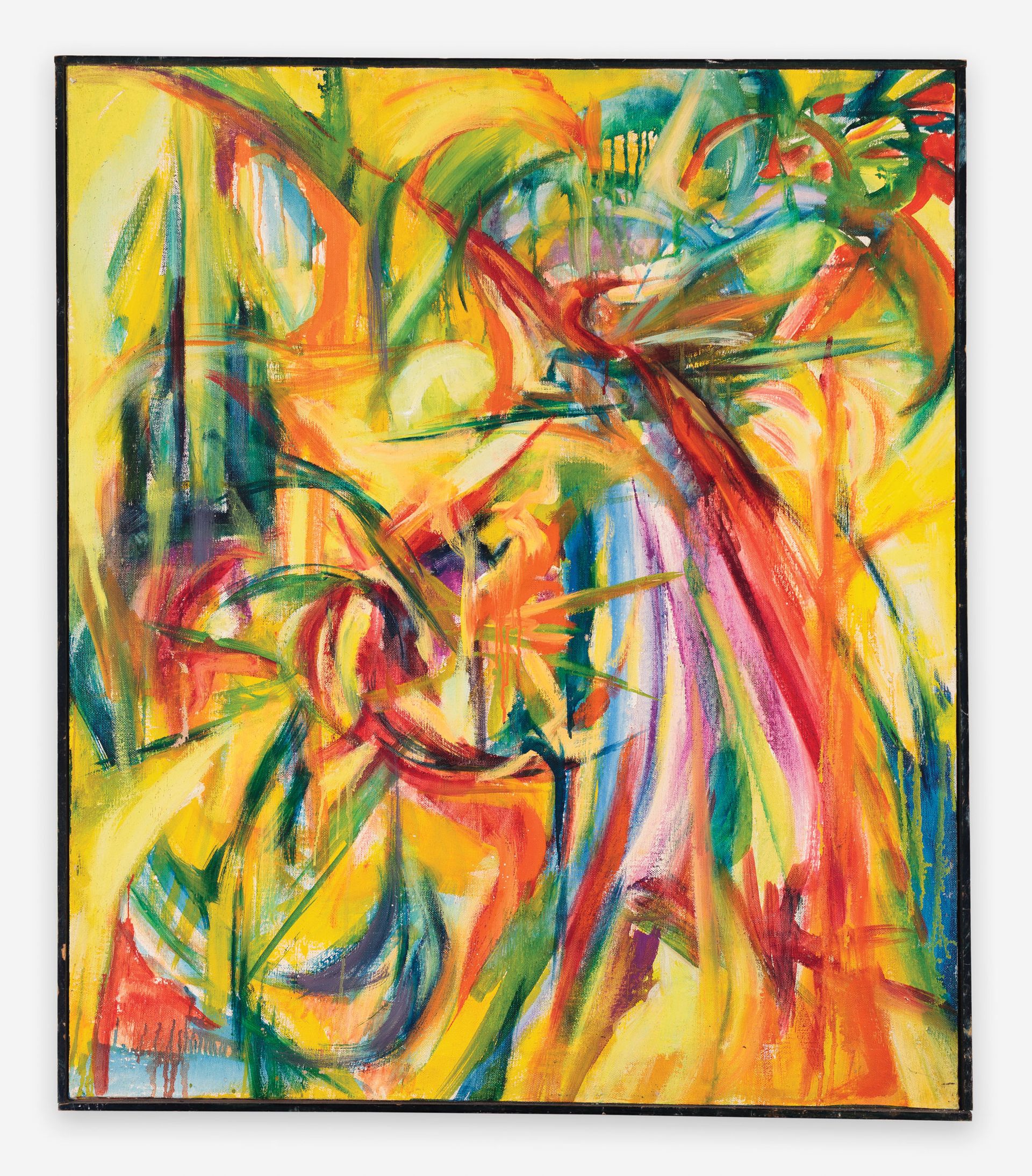

Carolee Schneemann's Pin Wheel (1957) Courtesy of the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Galerie Lelong & Co., Hales Gallery, and P.P.O.W, New York. © Carolee Schneemann Foundation / ARS, New York and DACS, London

Schneemann’s attraction to gestural painting was partly influenced by Paul Cézanne, whom she discovered at Columbia University in 1955, and in whose work, as she put it, “the precision of the act of painting of space was incomparable”. Schneemann took Cézanne’s flatness and fragmentary strokes and painted her first landscapes (she liked to spend summers depicting the mountains of Colorado). Her most complex paintings, such as the lush, loose, colour-saturated Pin Wheel (1957), which she mounted on a rotating potter’s wheel, she considered experiments beyond the canvas. “I had extended the dimensionality of my paintings,” she once said, to encompass “elements projecting out into space”.

The idea of experimenting with another medium came from two friends, the sculptor Claes Oldenburg and the dancer and choreographer Yvonne Rainer. In 1961, shortly after arriving in New York, they suggested she participate in performances including Oldenburg’s Store Days (1961). Oldenburg was known for his installations and experimental performances, and his method was to use fragments—“a collage of living parts”, as he put it—which presented new possibilities for Schneemann’s work.

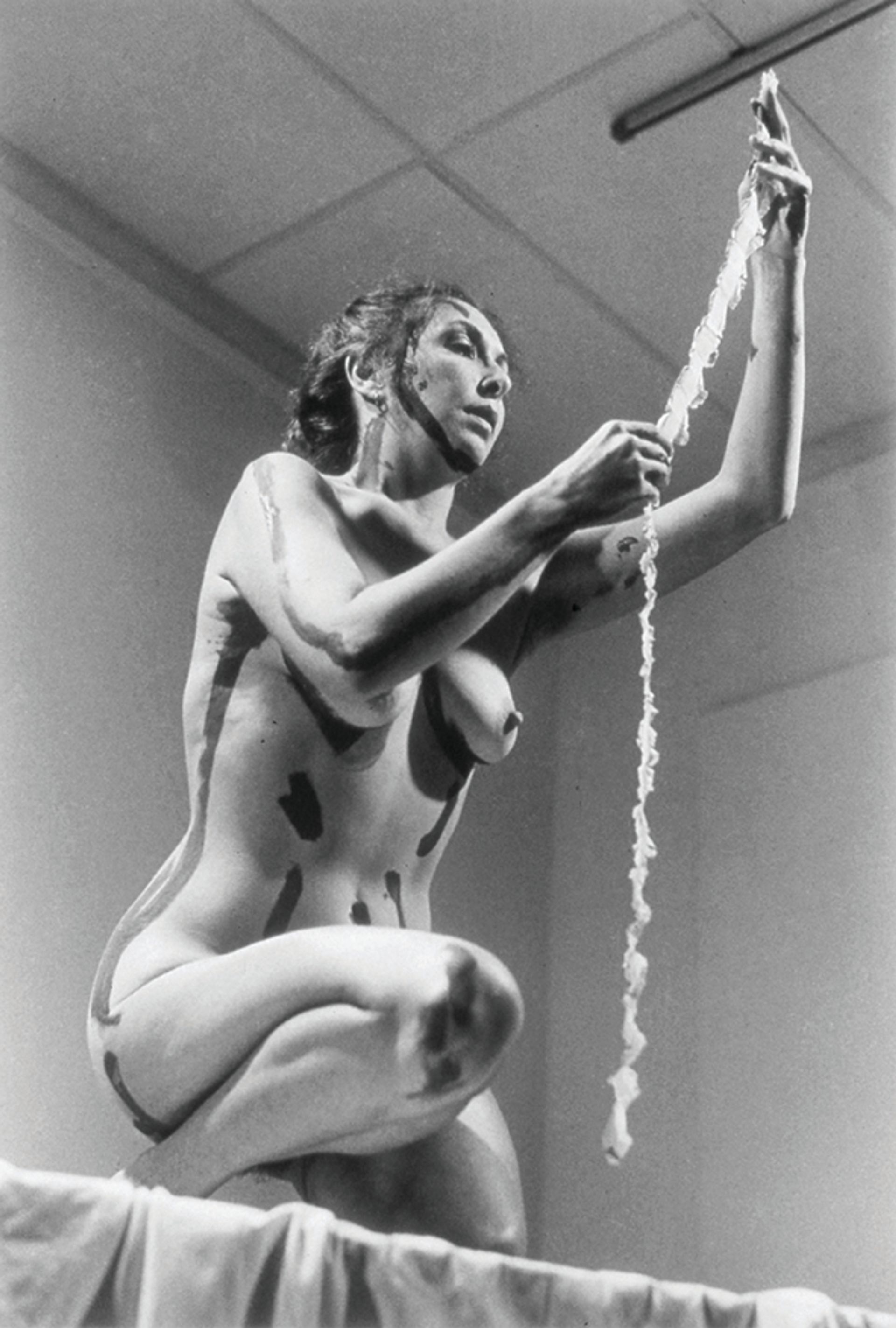

Her first performance was Glass Environment for Sound and Motion (1962); described as an enlarged collage, the setting determined any action or gesture of performers and audience. In the 1970s, she began working with her own body as, she claimed, a distinctly female way of making art. Critics sometimes derided her performances as “bodily” and “pleasurable” with “nothing conceptually substantive to say”. Her riposte came in the form of Interior Scroll (1975 and 1977), a performance in which she read from a slender roll of paper drawn directly from her vagina. Her monologue urged the audience to be prepared for the sexism that women confront in the art world. Schneemann once jokingly described herself as the “cunt mascot on the men’s art team”.

Carolee Schneemann performing Interior Scroll (29 August 1975)

Women Here and Now, East Hampton, New York

Photo: Anthony McCall

Schneemann’s work “addresses women’s bodily autonomy—from celebrating sexual desire and challenging taboos around menstruation to confronting histories of oppression, objectification and exclusion”, says the show’s curator Lotte Johnson, adding it still resonates today, “connecting to Roe vs Wade and the current war resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine”. The show will end with antiwar works, including Viet-Flakes (1965), a response to the brutality of the Vietnam War. Schneemann’s work proposes that the human body and all its issues should be at the centre of politics—and that despite humanity often repeating its mistakes, there are other ways.

• Carolee Schneemann: Body Politics, Barbican Art Gallery, London, 8 September-8 January 2023