Hovering high above visitors to Zürich’s main railway station is a figure some in the city have taken to calling the “fat angel”—a voluptuous blue-skinned, golden-winged sculpture by Niki de Saint Phalle. Colourful, joyous and liberating, it represents the best-known aspect of the the French-American artist’s work. An upcoming exhibition at the city’s Kunsthaus will introduce Zürchers to the, often darker and more disturbing, other side.

“Niki is well known in Switzerland,” says the exhibition’s curator, Christoph Becker. “But people here have a certain image in mind when they think of her work. They don’t know the rest. And the rest is spectacular.”

Politicians today talk about ‘inclusivity’ but she was the first to just do itChristoph Becker, director of Kunsthaus Zürich

The exhibition tells her story chronologically, connecting her biography to the work. She was born Catherine Marie-Agnès Fal de Saint Phalle in 1930. Her upbringing on New York City’s Upper East side was “hellish”—her aristocratic French father sexually abused her from the age of 11 and her mother was temperamental and violent. She married at the age of 18 and lived a bohemian lifestyle travelling around Europe with her husband and young daughter.

De Saint Phalle began making art during convalescence from mental illness in Nice in 1953—a treatment that also saw her subjected to electroshock therapy. She started painting densely worked canvases and fell in with a group of avant-garde artists who including the Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely, whom she later married. The show includes several of the small assemblages she made during this period, some no bigger than a hand, which were influenced by Tinguely and also a formative visit to Antoni Gaudí’s Parc Güell in Barcelona.

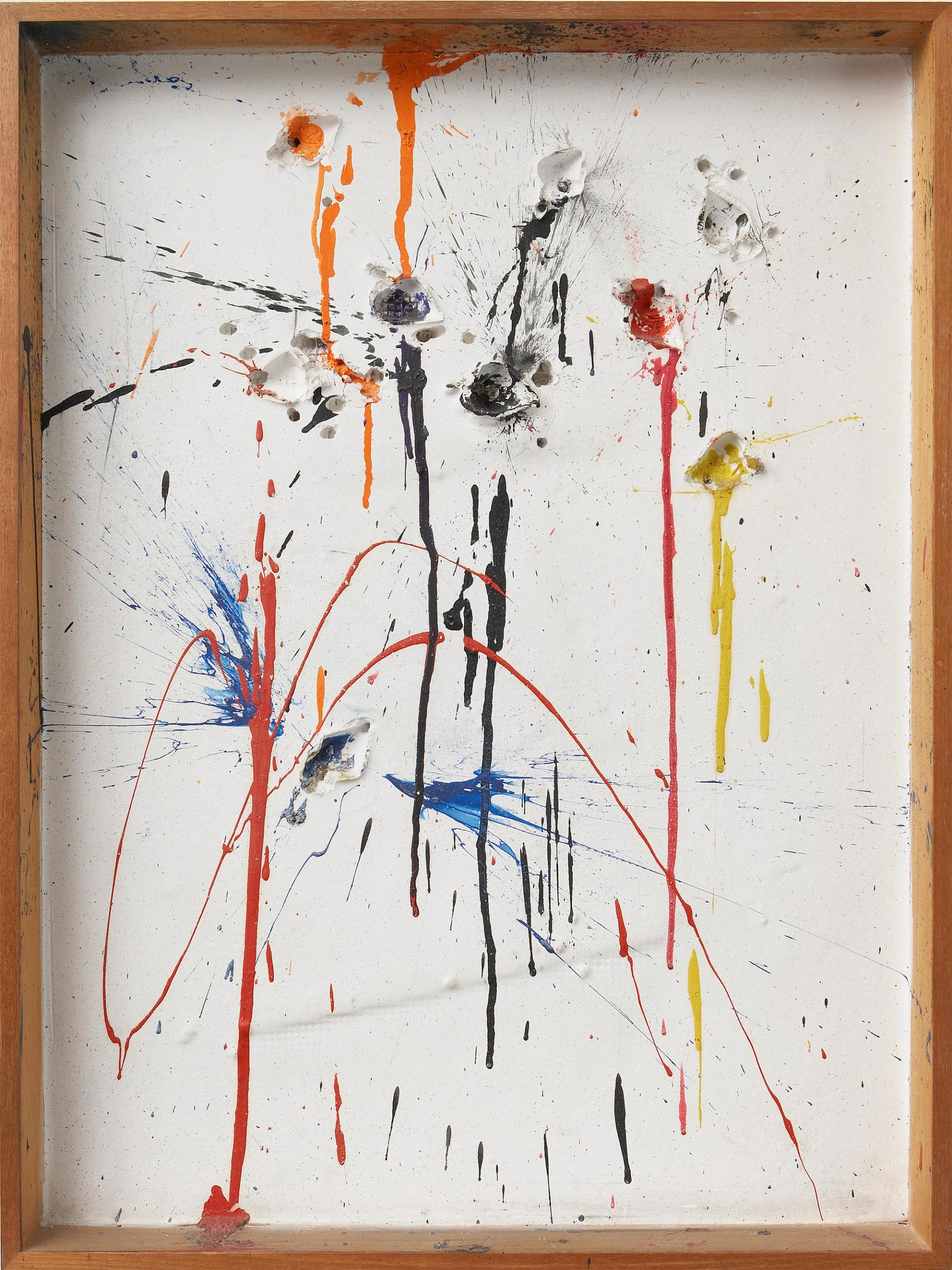

De Saint Phalle also started to involve the audience in her work, early steps in what the exhibition calls her “pivotal contribution to the art of performance”. One day in 1961 she was visiting an exhibition of her work titled Portrait of My Lover, which encouraged gallery-goers to throw darts at a target placed above a man’s shirt and tie and, she later wrote, “Flash! I imagined the painting bleeding—wounded; the way people can be wounded. For me, the painting became a person with feelings and sensations.” She borrowed a gun from a fairground, prepared a canvas with plastic bags of paint, and invited her friends to take turns firing a shot.

The exhibition features several of these Shooting Paintings, including one made for the 800th anniversary of Notre Dame. Plastic toys, devotional figures and other pieces of bric-a-brac are collaged into the shape of the cathedral’s front; three red trickles of paint show where the bullets landed and recall Christ’s wounds. In a typical piece of self-marketing, De Saint Phalle had herself photographed with the work and a gun outside the cathedral itself (as a teenager she had worked as a model for Vogue).

Niki de Saint Phalle's Shooting Painting (Tir), Edition 7/100 from the Edition MAT, 1964 © 2022 Niki Charitable Art Foundation, All rights reserved / ProLitteris, Zurich

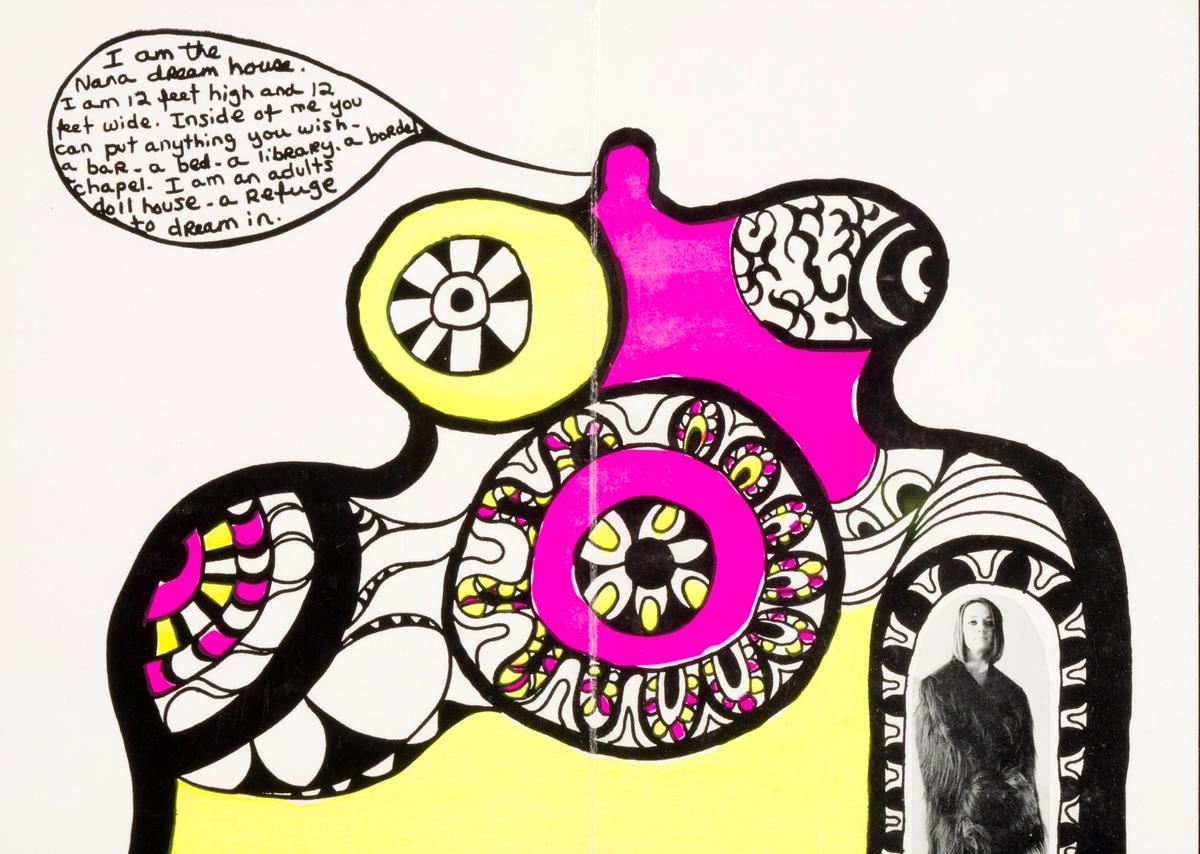

If the Shooting Paintings secured her a place in art history, it was the 1966 exhibition at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm that gained her wider fame. She had already started creating the Nanas—the brightly patterned female forms that include the Zürich station angel—but this was to be the biggest. Around 25m long and 9m high, Hon was a giant female form that visitors could walk into—entering via her vulva. The sculpture was sadly taken apart after the exhibition closed, but in Zürich there will be maquettes and a film.

Other key pieces are also too big to make it to the exhibition—despite it having more than 100 works and being one of the largest of her work in Europe for several years. The last decades of De Saint Phalle's life were spent on the sprawling Tarot Garden in Tuscany, a whimsical wonderland of giant sculptures, some big enough to use as a house or studio. The latter part of the exhibition does include another strand of her work however—De Saint Phalle campaigned for several social causes, including a widely published pamphlet about the Aids crisis and participated in campaigns against climate change and American gun laws. She died in 2002 of emphysema, caused she believed by dust fibres and chemicals from her art materials.

This is Christoph Becker’s last exhibition as director of the Kunsthaus Zürich—he is handing over the reins after 20 years this autumn. He hopes this final show will be popular with the public. “People love her, they are very close to her works. She is authentic, open about herself and people can find themes in them that connect to their lives…. Politicians today talk about ‘inclusivity’ but she was the first to just do it.”

• Niki de Saint Phalle, Kunsthaus Zürich, 2 September-8 January 2023; Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 3 February-21 May 2023