On the 75th anniversary of partition, it is worth remembering how the event displaced not only people across the Indo-Pakistan border, but heritage too. Indeed, to this day this historical division has ramifications for the study of antiquities: a reality no better exemplified than by the Chandayan of Mulla Da’ud—a landmark of South Asian literature and art

Little known outside of the scholarly community, the Chandayan was composed in 1379 by the Sufi spiritual leader Da’ud, and narrates the love story of Lorik and Chanda. Written in a premodern vernacular known as Avadhi, it survives as a masterful work of transcultural aesthetics, in which literary sensibilities from Sanskrit, Persian, Arabic, and Indic vernaculars merge.

Dispersed in collections across the world, only five copies of the Chandayan’s early illustrated manuscripts survive from the 15th and 16th centuries. But, as with many antiquities, partition severely altered one of these copies, a manuscript now known as the Lahore-Chandigarh Chandayan.

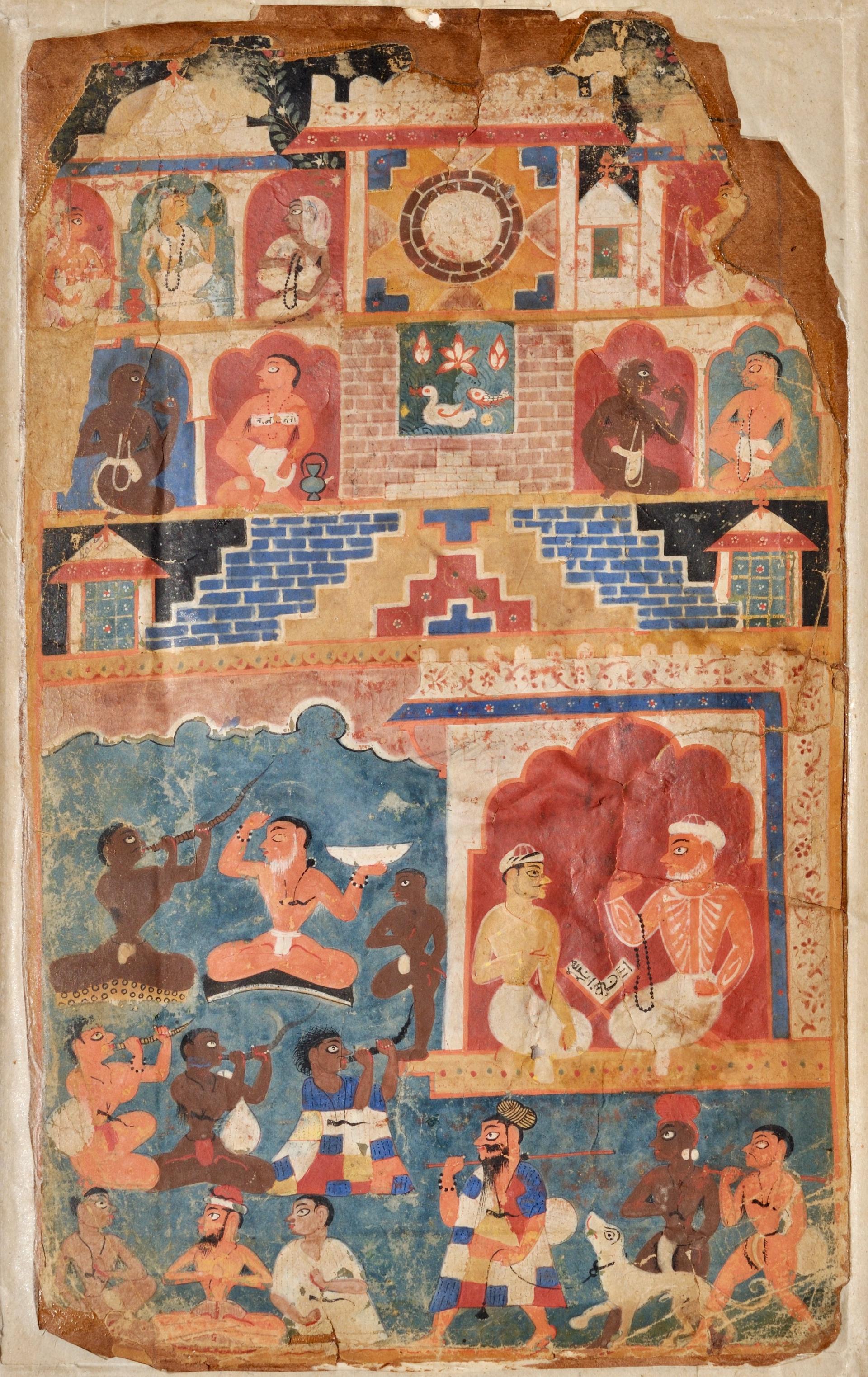

Only 24 folios of the Lahore-Chandigarh Chandayan manuscript remain, of what may have been over 250 when they were first commissioned in the 16th century. These pages are currently spread across three museums: the Government Museum and Art Gallery in Chandigarh (in India), and the Lahore Museum and the Karachi Museum (both in Pakistan). Acquired by the Lahore Museum before 1947, this Chandayan manuscript was among the objects of art and archaeology in its permanent collections that was split between India and Pakistan in response to the 1947 partition. Not all manuscripts were cut up for financial gain; some were dismembered for national anxieties.

At partition, the Lahore Museum became a fulcrum in the debate over governmental assets and liabilities, which were in theory subject to the rules of division established by the Partition Council. However, the museum’s intimate ties to both provincial and central governmental bodies meant that objects within its collections received different treatment during the division process. While its archaeological stores were subjected to a 50:50 split with India, its permanent collections were divided 60:40 in line with the ratio used to divide the territory of colonial Punjab. This meant that 60% of the museum’s painting, sculpture, textile, and decorative arts sections stayed with West Punjab in Pakistan, while 40% were given over to East Punjab in India.

Museum officials were keen to abide by these ratios at all costs, so much so that, in some cases, the division process resulted in the fragmentation of whole objects and manuscripts. The Chandayan, which had been acquired by the Lahore Museum unbound, was separated to match these numbers, with 14 folios allocated to museums in Pakistan and 10 folios given to India. While it is not uncommon today for manuscripts like the Chandayan to have parts in multiple collections and places, what makes the dispersal of the Chandayan unique is that it occurred with and for the division of the Indian subcontinent and today remains separated by a contentious national border that prohibits its physical reconciliation.

Ultimately, these ratios only tell a fraction of what this division process entailed. Like a vast number of works of South Asian art, the Chandayan presents the irony and futility of such sordid acts of fragmentation. How to cut up a manuscript whose language is Avadhi, the very Sanskritised idiom of the 16th-century Ramcharitmanas of Tulsidas, but is written in an Arabic script? How does one enact the division of Hindu/India and Muslim/Pakistan on an object that comes from a world without such binaries?

Da’ud, in many ways, anticipates these tensions in the beginning of the romance when he writes, “I became aware of the written word’s power—sang a Hinduki song written in Turki script,” emphasising that the Arabic script of the 14th-century was not best suited for the sounds of the Avadhi vernacular (trans. Richard Cohen). The Lahore-Chandigarh Chandayan came with the added complication of having captions in its illustrations in the Indic kaithi script, a further challenge to the hyperrational logic of the division process.

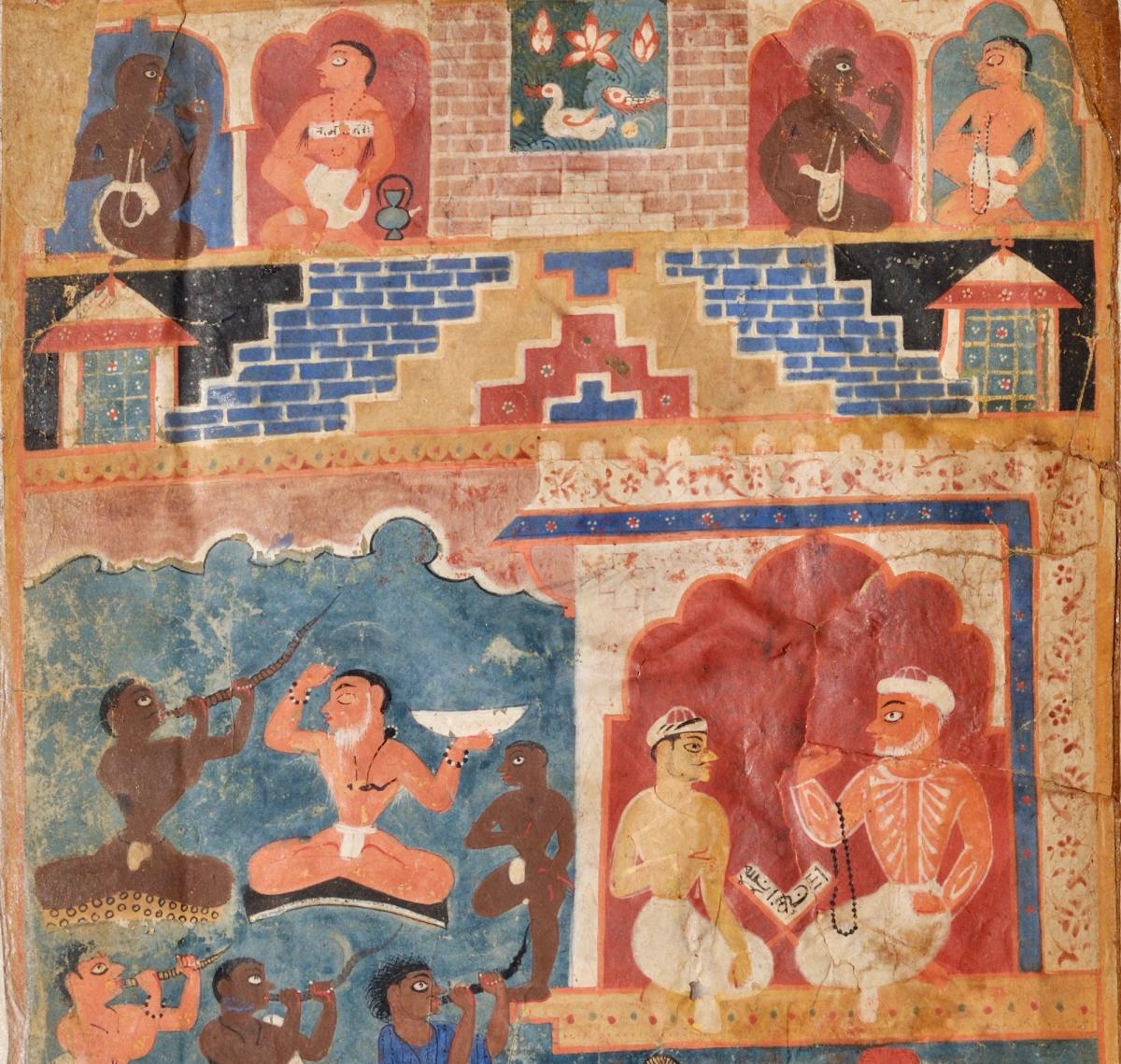

Canto 20 of the Chandayan, Attributes of the temple by the pool and the yogis present there. Attributed to Delhi-Agra region (1525-40). Reproduced with permission of the Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh, K-7-30-H.

That heritage like the Chandayan was dispersed at partition, in a manner that compromised its physical integrity, is cause for alarm. But it is not entirely surprising, considering the wider stakes of owning a piece of its history. If partition saw India lose access to key archaeological sites at Mohenjodaro, Harappa, and Taxila, and Pakistan lose custodianship of key Islamic monuments like the Taj Mahal, the fight over art and antiquities in 1947 held more than the promise of ownership, it held the promise of control: to write, display, and create history in the image of each’s own nation. The Indo-Pakistani border restricts more than the movement of people, it regulates access to history and the production of knowledge. But, can language, such as the oral romance of the Chandayan, not traverse this border?

The task of creating a critical edition of the Chandayan’s text through its manuscript copies is a massive undertaking, marred both by the issue of the text’s scripts, but also because of the dispersal and lack of access to all of its fragments. Of the physical copies held by museums, the Lahore-Chandigarh codex has probably fared the worst, as it was split across a border, which has hardened in many ways.

This continues to affect scholarship around the Chandayan. While several of the key Mughal chronicles have been translated, only in the upcoming year will the Indian publisher Marg publish a full translation of the Chandayan by Richard Cohen. And only in 2018 did the professor of Hindi literature, Shyam Manohar Pandey, publish an updated critical edition of the text.

In today’s India where roads, cities, and monuments associated with the Mughals are being systematically renamed and erased from memory in the name of Hindutva, what does an object made before Mughal rule and its experience during partition teach us about the nation’s artifice? And what does it teach us about art history? Mughal monuments are an easy target because of their global visibility, but Islamic art of South Asia extends far beyond the imprint of the Mughal dynasty.

And yet, it is not only Muslim heritage of India that is under threat. A whole-scale remaking of the past is underway, fragmenting the landscapes of entire cities like modern Delhi. The visual is being weaponised to further split and divide us. In these times, the Lahore-Chandigarh Chandayan, in its totality beyond borders, becomes a horizon for dreaming for alternative futures.

•Vivek Gupta is a postdoctoral associate at the University of Cambridge

•Aparna Kumar is a lecturer on art and visual cultures of the Global South at University College London