Scholars have expressed concern over the proposed sale by Christie’s London on 24 October of two illuminated pages, taken from The Paths of Paradise, a 15th-century manuscript made for the Timurid ruler Sultan-Abu Sa'id Gurkan. A third folio was presented earlier this month at Frieze Masters by dealer Francesca Galloway.

Armen Tokatlian, a Paris-based art historian and consultant, says all three come from "the recent wreckage of a cultural monument of Persian art". In Prospect magazine, the art historian Christiane Gruber says the folios were separated from a royal manuscript she has “trailed for 20 years now”.

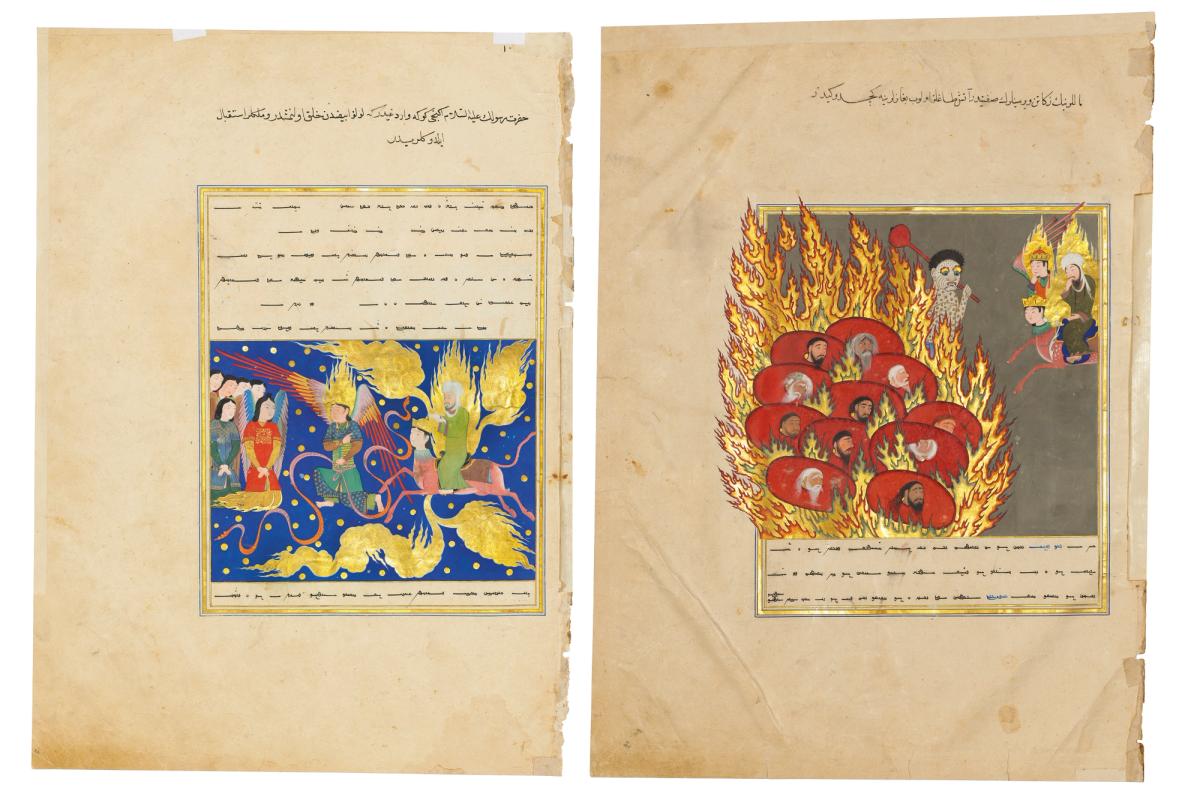

The Paths of Paradise was commissioned by Sultan-Abu Sa'id Gurkan around 1465, in Herat or Samarkand. “It was held in the Treasury of Ottoman Sultan Selim I (who reigned from 1512 to 1520), and remained intact until the end of the 20th century”, Tokatlian says. One folio at Christie’s auction, showing the Prophet approaching angels, is estimated to make between £700,000 and £1m. A second double-sided folio, depicting "the hell reserved for the misers and the hell for the flatterers", carries the same estimate.

"Beyond the aesthetic value of the illustrations and the Turkic text written in Uyghur script, depicting Prophet Muhammad’s ascension to heaven, this is a monument of the Persian art of the book from Central Asia, and is of paramount interest for scholars," Tokatlian says.

According to Gruber and Tokatlian, the only other existing related manuscript, with an earlier princely Timurid patronage, is held at the National Library of France—it probably served as a model for this manuscript. That example, dated 1436 and written in Herat in Chaghatay language and Uyghur script, was purchased in Constantinople on behalf of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the minister of the French king Louis XIV.

Christie’s catalogue states only that both lots come from a private UK collection and were previously sold privately by Christie’s in 2016. However, the provenance of the complete volume is not mentioned. Quoting Emel Esin, the author of an article in The Arts of the Book in Central Asia (Basil Gray, Paris 1979), Tokatlian says that it was housed in the 1960s at the Nizam Library in Bahawalpur, in Pakistan. Its owner removed it and brought it to the UK in around 1970. “It was seen by specialists still bound and photographed after its entry to the UK," according to Eleanor Sims in a 2014 article published in the Journal of the David Collection. A photograph showing the manuscript still bound was published in C.J. Gruber's El Libro de l’Ascención in 2008.

Tokatlian says that after the death of the owner around 25 years ago, the family separated the 61 extant double- or single-sided illustrations to share among the heirs. “Scholars were astounded when six folios surfaced in 2012 in the David Collection [a museum in Copenhagen founded by the Islamic art collector Christian Ludvig David],” he says. Four years later, several pages were sold by Christie’s private sales department (one of the owners, Francesca Galloway gallery, says its folio was not purchased then). Around 2014, the Sarikhani Collection in London, one of the largest private collections of Iranian art, bought three additional folios.

“The motivation for this sordid practice is obvious,” Gruber says. “These are incredibly beautiful works of art, and incredibly valuable: each folio is estimated to sell for about £1m. Their sale, though, raises a number of important ethical issues over how collectors and art galleries treat Islamic art.”

Christie’s tells The Art Newspaper that it understands that the folios come from the royal manuscript housed at the Pakistani library, before it came to the UK in the early 1970s. Christie’s underlines that it has the “full right to sell” and is “confident with the provenance”. The dismemberment of ancient Persian manuscripts, was, says a spokeswoman, “sadly, a common practice in the past”, one that “is now discouraged”. She underlines that “these folios were separated almost 30 years ago” and insists that Christie's “would not sell any object where there isn’t clear title of ownership and a thorough understanding of modern provenance”.

However, that might not be enough to satisfy the scholars. While Tokatlian regrets that the complete history of such treasures may be “obscured” by the art market, Gruber is more hardline, calling for a “boycott of such items” in order to discourage these “destructive acts".