In 1940, the Mexican artist Diego Rivera painted his fresco The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on This Continent, in front of a live audience at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco. Over the course of seven months, he and a group of assistants filled its ten steel-framed cement panels with images of Aztec pyramids and philosophers; Thomas Edison and Henry Ford; and workers toiling away in factories, mines and fields. These symbols of history, politics and labour from boths sides of the US-Mexico border embodied Rivera’s vision of the Americas as a single entity, separated from Europe by a shared history of indigenous culture and subsequent colonisation. “I mean by America,” the artist said in 1931, “the territory included between the two ice barriers of the two poles. A fig for your barriers of wire and frontier guards.”

The mural, more commonly known as Pan American Unity, is the centrepiece of Diego Rivera’s America, a vast survey opening at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA). The show brings together 150 frescoes, paintings and drawings made between the 1920s and 1940s, when “Rivera and many of his colleagues in Mexico saw art as a weapon for social change”, says the show’s curator James Oles. This is the first big Rivera survey organised by theme, highlighting the artist’s most prominent interests during that period: the daily life of mothers, labourers and indigenous people; symbols of his communist politics; and his vision of solidarity across borders.

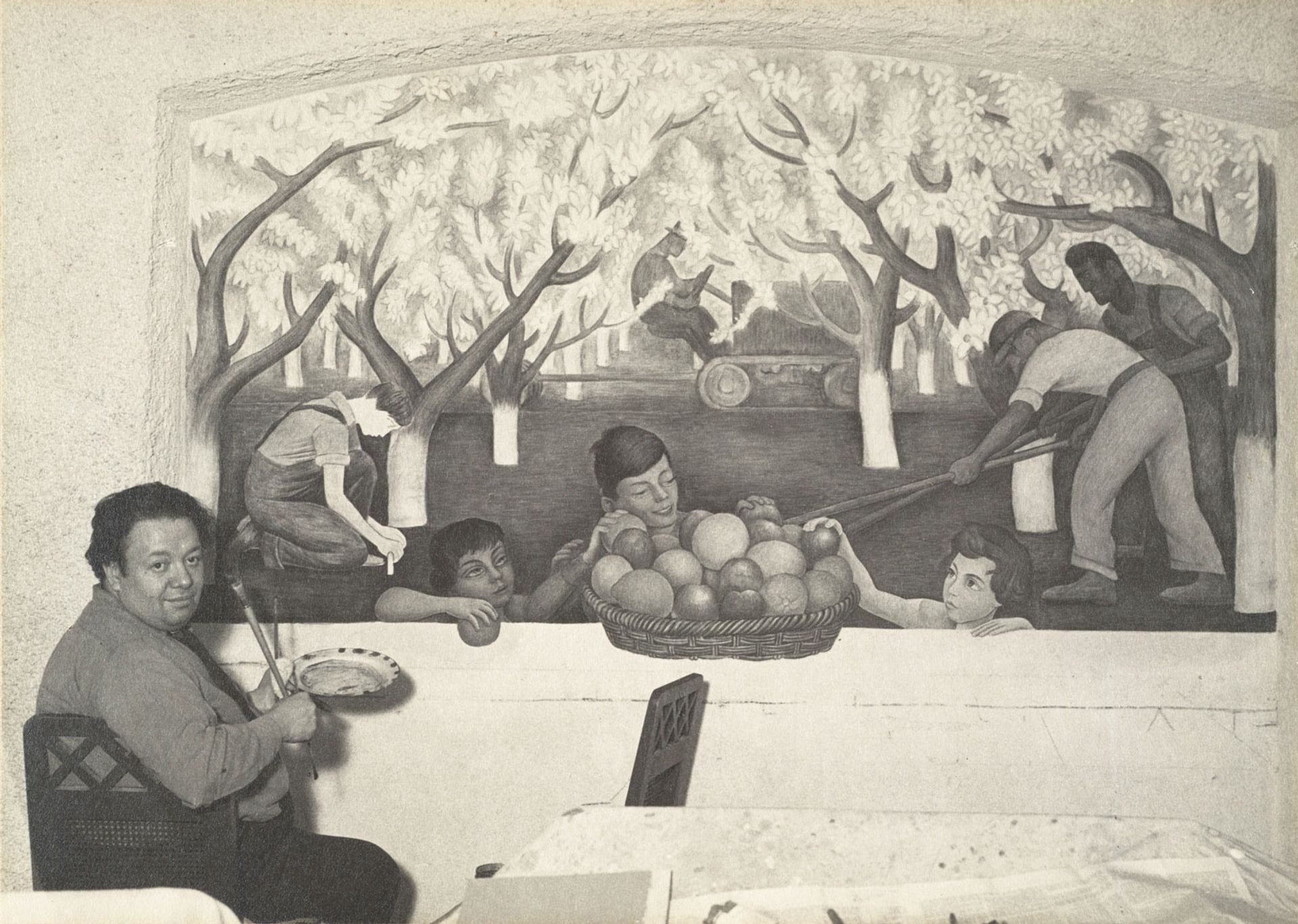

Ansel Adams's photograph of Rivera painting the fresco Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees (1930-31) © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Pulling from both private collections and SFMoMA’s own holdings—one of the largest collections of Rivera’s works in the world—the exhibition brings to light a number of previously unseen pieces, while also emphasising Rivera’s often overlooked relationship with the Bay Area. When he and Frida Kahlo first arrived in 1931, “California was for me the ideal intermediate step between Mexico and the United States,” he said of the formerly Mexican land where agriculture coincided with industry. His work depicts the region’s farmers and miners, and examples by other artists included in the show illustrate the close friendships he and Kahlo had there, including a portrait of Rivera by Ansel Adams. Rivera’s work was well-loved by local patrons Albert Bender and William Gerstle, and the show does not elide the contradictions of two avowed communists socialising with wealthy collectors and industrialists. Rivera was “reliant upon, yet constantly resisting the systems of patronage that enabled his work”, Oles writes in the catalogue.

San Francisco was the site of Rivera’s first murals in the US—The Allegory of California, The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City and Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees (all 1931)—represented in the exhibition by preparatory drawings and vibrant street footage, shown as large projections on the gallery walls.

Diego Rivera's Woman with Calla Lilies (1945) Courtesy of Galeria Interart; © 2022 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / ARS, NY. Photo: Scott Cramer

Pan American Unity, Rivera’s final US mural and his largest portable fresco, was transferred panel by panel from its home at the City College of San Francisco last year to SFMoMA, on loan until 2023. Oles writes in the catalogue that “it is mainly on the walls that we find the artist as an activist, using public art to expose the political crises and moral failures of his time”. Rivera’s murals are also his most radical compositions, the curator adds: “If a cubist still-life wants to give us a sense of a face seen from different angles at different moments, Diego Rivera’s murals, denying Renaissance perspective altogether, are looking at history and culture from different angles at different moments that would be impossible to observe in real life.”

• Diego Rivera’s America, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 16 July-2 January 2023; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, 11 March-31 July 2023