“Never shall we forget the enthusiasm of the doctor wading to his knees amongst the viscera of the [whale], alternately cutting away with his large and dexterous knife, and regaling his nostrils with copious infusions of snuff.” So runs the extraordinary description of the activities of the 19th-century anatomist, Reverend John Barclay, an Edinburgh-based lecturer who was called in to dissect a dead Beluga whale in 1815. Barclay was one of the often colourful figures—along with Robert Knox, William Hunter and three generations of anatomy professors called Alexander Monro (“primus”, “secundus” and “tertius”)—who helped put Scotland’s capital on the map as a centre of excellence in medical teaching, and inadvertently laid the ground for one of the most notorious crimes of the era.

Hence the appropriateness of Edinburgh’s National Museum of Scotland staging an exhibition called Anatomy: A Matter of Death and Life, which examines this particular conjunction of medical advancement, artistic accomplishment and gruesome lawlessness—the last, of course, being the murderous activities of the graverobbing “resurrection men” William Burke and William Hare. The show aims to tell these three stories alongside each other, taking as its starting point the new thirst for scientific knowledge in the Renaissance, encapsulated by amazing anatomical drawings by Leonardo da Vinci on loan from the Royal Collection.

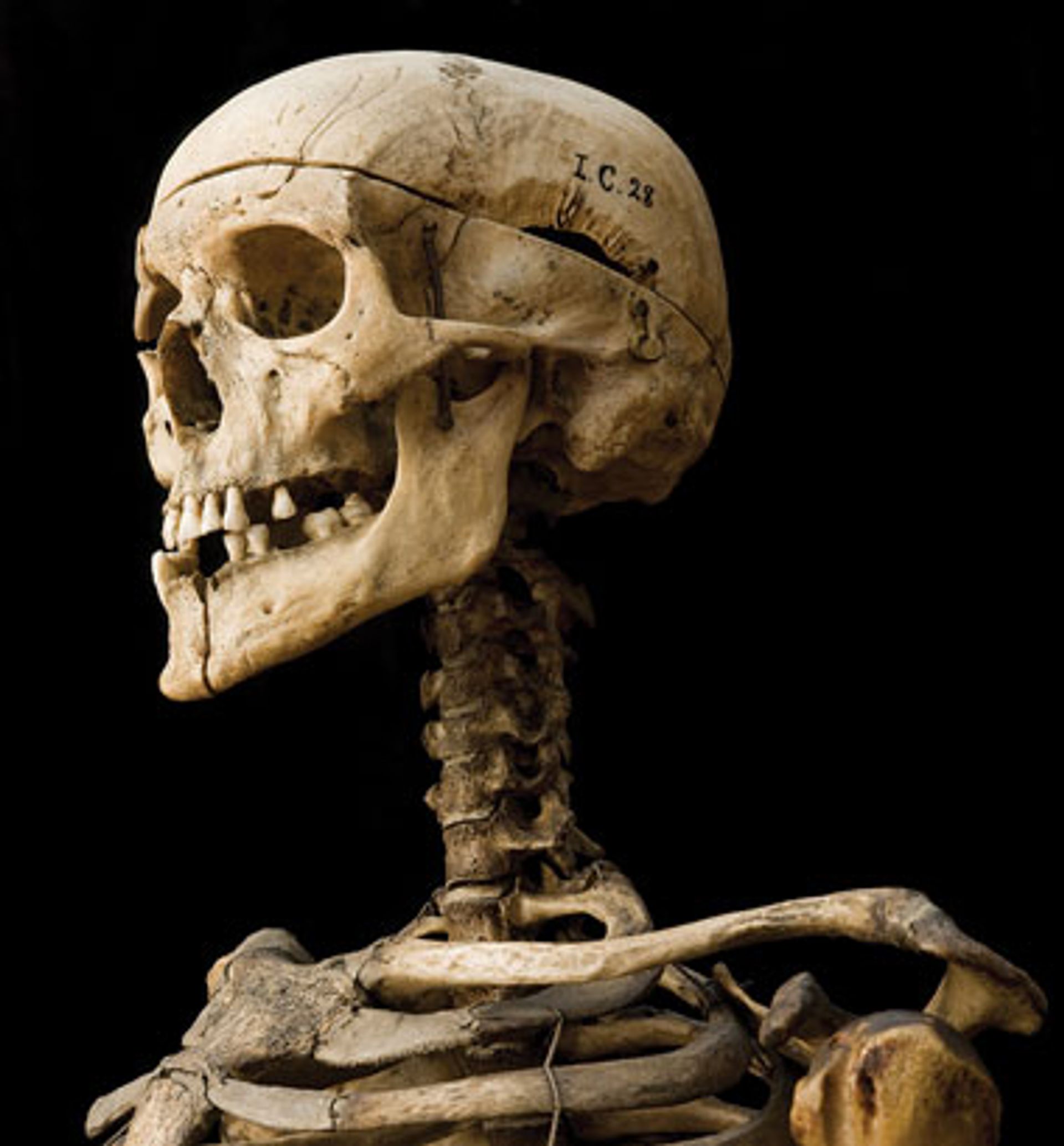

Skeleton of William Burke © Anatomical Museum collection, University of Edinburgh

The exhibition curator Tacye Phillipson says the process works both ways. “The skills of looking closely at something, and making sense of what was seen, are central to both art and anatomy,” she says. “Anatomists needed the skills of artists to portray their discoveries, and help other people see the same thing in a dissection. Artists have found a knowledge of anatomy to be useful for their own work; portraying people, or horses, or dogs in animated and lifelike poses can be helped by a knowledge of what was under the skin.”

Phillipson’s exhibition showcases a number of distinctive styles and forms that developed around anatomy: most remarkable are écorché (“flayed”) figures, minutely detailed models of the human body stripped of skin and fat, intended to demonstrate musculature and bones, that began to appear in the 18th century. Another prolific style is the “anatomy lesson” picture, with the show including examples such as Adriaen van der Groes’s Dissection of a Malefactor (1709) and Cornelis Troost’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Willem Röell (1728). Phillipson says she particularly admires Johann Zoffany’s painting Hunter Lecturing at the Royal Academy (around 1772), as well as the beautiful illustrations to be found in the classical textbooks of the era. “In effect, they turn the insalubrious work of the anatomist into clean and pure delineated knowledge,” she says.

Insalubrious would describe the work of the “bodysnatchers”, gravserobbers who would dig up fresh corpses to sell to Edinburgh’s anatomists as bodies were in desperately short supply; only executed criminals were officially allowed to be used. (Interestingly, stealing a corpse was not a crime, but bodysnatchers could be prosecuted for stealing clothes if any were still on the body.) Encouraged by the money to be made, Burke and Hare, and their respective wife and partner, were suspected of killing at least 16 people to sell on—though after Hare turned King’s evidence, Burke was the only one convicted, for a single murder, and hanged in 1829. Burke's skeleton will be included in the show.

As Phillipson points out, this grisly history happened only yards from the museum. “This is a very Edinburgh story and so much happened right around our site,” she says. “We thought it was a story we could tell well.”

• Anatomy: A Matter of Death and Life, National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2 July-30 October