Sam Gilliam, an abstractionist known primarily for his Drape paintings—unstretched canvases that are hung from ceilings and pinned to walls—as well as for being the first Black artist to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale, has died. Gilliam died on 25 June, aged 88. The cause of death was renal failure. His death was announced by his New York gallery Pace, as well as his Los Angeles gallery David Kordansky.

The seventh of eight children, Gilliam was born in Tupelo, Mississippi in 1933, though the majority of his childhood was spent in Louisville, Kentucky. His father was a carpenter and a railroad worker and his mother was a schoolteacher. Gilliam earned his Bachelor’s degree in fine art from the University of Louisville followed by a brief stint as an army clerk in Japan, after which he returned to the University of Louisville for a master’s degree in painting, graduating in 1961. The following year he and his first wife, Dorothy Butler, moved to Washington, DC, where she had been offered a job at the Washington Post, becoming the publication’s first Black reporter, and Gilliam took a position as an art instructor at a local high school. He would live and work in DC for the rest of his life.

Sam Gilliam, Double Merge, 1968, installation view, Dia:Beacon, Beacon, New York. © Sam Gilliam. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York, courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

Gilliam was painting at the time in a primarily figurative mode, and subsequently stated that his move toward abstraction came with encouragement from the Washington Color School—a group of artists that included Kenneth Noland, Morris Louis, Thomas Downing and others. Downing in particular acted as a mentor for the young artist, encouraging him to develop a looser, more fluid painting technique. Though he was never officially a member of the Washington Color School, he was often considered the face of the movement’s second wave, according to a spokesperson for David Kordansky.

It was in this era that Gilliam began the two bodies of work for which he is most well known: his Beveled-edge and Drape paintings. In 1967, he began the beveled-edge paintings (also known as the Slice paintings) in which he stained raw canvas with fluidly applied acrylic paint before folding or crumpling the material while the paint was still wet, then mounting it onto custom-made stretcher bars with beveled edges. In 1968 he began the Drape paintings—his most iconic series—in which he applied his paint in a similar manner then did away with the stretcher bars altogether, opting instead to let his canvases hang fluidly from the wall or ceiling.

“My Drape paintings are never hung the same way twice,” Gilliam told The Art Newspaper in 2018. “The composition is always present, but one must let things go, be open to improvisation, spontaneity, what’s happening in a space while one works.”

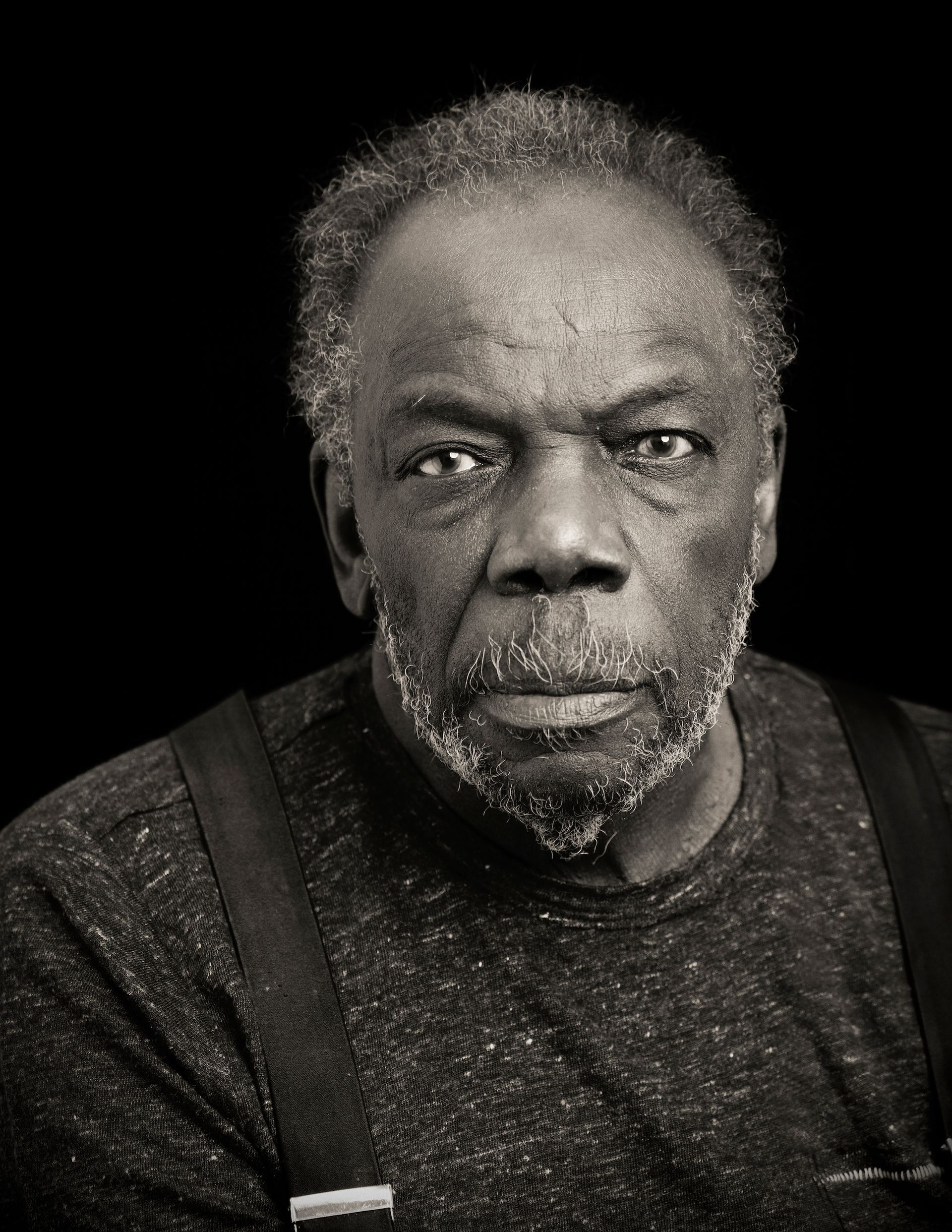

Sam Gilliam Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Pace Gallery. Photography by Fredrik Nilsen Studio

In 1969, an exhibition at DC’s Corcoran Gallery of Art—now a leg of George Washington University called the Corcoran Gallery of Art and Design—featured a number of these Drape paintings, and the show proved to be Gilliam’s big break, garnering wide attention. Three years later, in 1972, he became the first Black artist to represent the US in the Venice Biennale.

“No one could forget the 75ft piece that Sam made for the American Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1972. It stole the show that year and made a profound impression on everyone who saw it,” Arne Glimcher, founder of Pace Gallery, wrote on the occasion of Gilliam’s death. “In truth, it was impossible not to feel the audacity, grandeur and complexity of what Sam was trying to do. He exploded the borders between sculpture, painting and installation. He reinvented colour and space in abstraction, and he’s kept doing that ever since. It’s been a thrilling thing to witness.”

Sam Gilliam, Green April, 1969. Collection of Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel, Switzerland. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles and Pace Gallery. Photography by Lee Thompson.

In the ensuing decades, Gilliam continued to push himself and his medium, wrestling further with the physicality of painting, though his commercial success came slower than that of other artists from his generation. This may have been the result of a racist system that routinely excluded artists of colour; it may have stemmed in part from his lack of desire to engage with the New York art world—Glimcher said that when he proposed showing Gilliam at Pace, the artist “explained that he had never wanted a strong commitment with any New York gallery”—or it may have been a combination thereof. Later in life, however, he saw a flurry of success, with solo exhibitions at museums including Dia:Beacon and Kunstmuseum Basel, and representation from Kordansky in Los Angeles starting in 2012 and Pace in New York beginning in 2019.

In 2017, he was again invited to exhibit at the Venice Biennale. “All that is happening now—the immigration crisis, the bombs, the gutting of the National Endowment for the Arts, the presidential corruption—was present in the 1970s. It seems worse now, but history, like art, is cyclical,” he told Artforum on the occasion of the installation. “To gesture at the cycles of history is art at its greatest capacity,” he added. “To me, art is about moving outside of traditional ways of thinking. It’s about artists generating their own modes of working. We need to continue to think about the whole of what art is, what it does. Even though my work is not overtly political, I believe art has the ability to call attention to politics and to remind us of this potential through its presence.”

Sam Gilliam, Seahorses, 1975, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia Photography by Johansen Krause. Courtesy of the artist, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, and Pace Gallery

A major exhibition of his work, Sam Gilliam: Full Circle, is on view now at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC until 11 September. “For more than half-a-century, Sam Gilliam role-modeled creative genius, artistic breakthroughs and professional persistence,” Duke University art historian and Hirschhorn board member Richard J.Powell said in a statement. “From his pictorial interpretations of draped splendor to his evocative accumulations of pigments and colours, he single-handedly reinvented painting. Sam Gilliam has made an indelible mark on modernism.”