“I’ve always listened to everyone, from Coltrane to Beyoncé, but not always while I work,” says Sam Gilliam during the installation of works for his show at the Kunstmuseum Basel (until 30 September), which focuses on the period from 1967 to 1973. This is the 84-year-old US lyrical abstractionist’s first major European exhibition.

Although “the relation between music and my work isn’t so direct, the structure of jazz is important”, Gilliam says. “My Drape paintings are never hung the same way twice. The composition is always present, but one must let things go, be open to improvisation, spontaneity, what’s happening in a space while one works.”

The African-American artist embodied the late 1960s jazz ethos in pushing his medium to its limits, creating experimental abstract works just like his musical heroes. In 1962, the Mississippi-born Gilliam moved to Washington, DC, where he came into contact with Colour Field painting. But Gilliam took a different path from the abstract painters of the period, peeling right back and dismantling the starting point for most painters—the canvas. In 1967, he began a series of works called slices, or bevelled-edge paintings, pouring diluted acrylic paint onto the unstretched, unprimed canvas, then folding or crumpling the fabric before stretching it on a bevelled frame after the paint had dried.

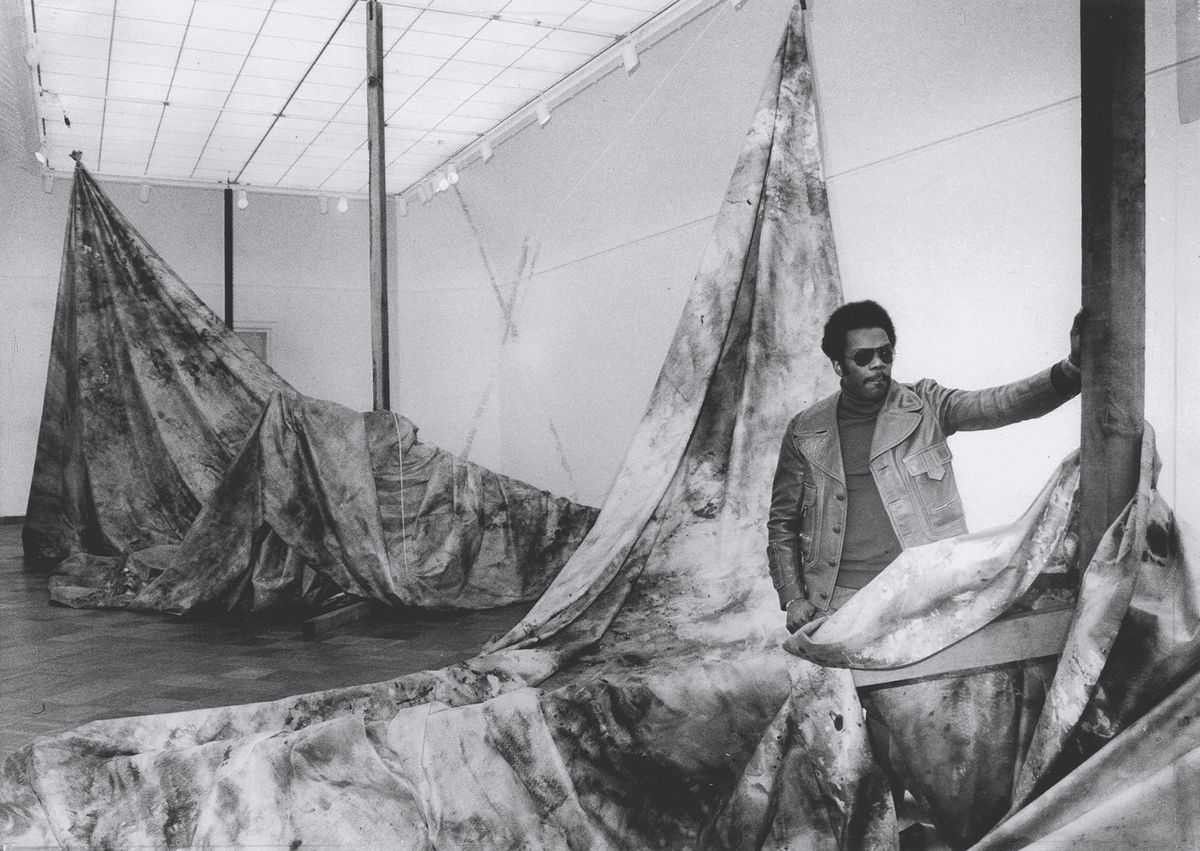

He went a step further when he started his Drape series in 1968. “That is when he made his most radical decisions, to completely get rid of the stretcher, to really advance painting in a way no one had done before,” says Josef Helfenstein, the director of the Kunstmuseum Basel and co-curator of the show with Jonathan Binstock, the director of the Memorial Art Gallery at the University of Rochester. Almost like curtains or tapestries, Gilliam began to hang the canvases in corners, from the wall and ceiling.

Sam Gilliam's Rondo (1971) Photo: Lee Thompson. Courtesy of the artist; Kunstmuseum Basel and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles © 2018; and ProLitteris, Zurich

Gilliam was “blurring completely the territory [of painting] and widening it in three-dimensional space, and also, in a way, in time: these pieces have a performative component; they’re never the same,” Helfenstein says.

The artist’s work “compares really interestingly” to that of his peers and he was “not the only one to have used canvas without stretchers,” Helfenstein says. “At about the same time, Richard Tuttle starting doing this and also some French artists from the group Supports/Surfaces,” he says. “But it was very different; it was still very much in the tradition of classical painting. And Tuttle’s works were not paintings; they were coloured fabrics. No one had done it in this huge architectural way that Gilliam did.”

His works from this period are often political—a reflection of the turbulent times in which they were made. While Gilliam has always believed that “abstraction is as political as representation”, some writers associated with the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s disagreed, as noted by Mark Godfrey in his catalogue essay for the recent Soul of a Nation exhibition at London’s Tate Modern, in which Gilliam’s work was shown. Some writers felt that “the role and responsibility of black artists was to create empowering images for their people”. Further still, black artists making abstract works were said to be “prostrating themselves before white institutions and producing work according to established white aesthetic ideals”, Godfrey writes.

My Drape paintings are never hung the same way twice. The composition is always present, but one must let things go, be open to improvisation, spontaneitySam Gilliam

But Gilliam argues that “the expressive act of making a mark and hanging it in space is always political. My work is as political as it is formal. Sometimes the politics are foregrounded by titles. For example, Green April (1968-70) [which is in the Kunstmuseum show] is the largest example of a suite of works responding to the April 4, 1968 assassination of Dr Martin Luther King Jr.”

Although “he really comes from the Washington Colour Field group, he goes wildly into a new territory”, Helfenstein says. This difficulty in categorising his work is, Helfenstein believes, one of the reasons that Gilliam was forgotten for so long. “It was the time of Minimalist art, it was the late period of Pop art, conceptual art,” which Gilliam did not fit neatly into, either. “Now he’s seen again in the broader historical context, which is really the goal of our show,” Helfenstein says.

The curator also notes that Gilliam was “sidelined” as an African-American for making abstract work that was not obviously and figuratively political. “You could see in that context [of the Soul of a Nation exhibition] how unique he was; there were very few abstract black artists at the time,” he says.

The recent resurgence of looking at histories of art that are not skewed towards white male artists has led to a renewed interest in many African-American artists who influenced today’s generation. Furthermore, “there are now African-American collectors with significant means who are very much focusing on African-American art,” Helfenstein adds.

Sam Gilliam's The Music of Color (1967–73) at the Kunstmuseum Basel Photo: Julian Salinas

One of the major markers of a renewed interest in Gilliam—and one that could not be missed by visitors—was his huge work Yves Klein Blue (2017) at last year’s Venice Biennale. This marked the return to Venice for Gilliam, who in 1972 became the first African-American artist to represent the US at the biennial when the curator Walter Hopps invited him and five others, including Diane Arbus, to participate. “I spent a week living in the American Pavilion, installing my work,” the artist says. “Showing at the entrance of the Central Pavilion 45 years later was liberating: one’s work is experienced more broadly; the reading is universal rather than national.”

“The reason why I thought this show would be especially appropriate here in Basel is because we have a well-known collection of post-war American art,” Helfenstein says, who had come to know Gilliam from his time as director of the Menil Collection in Texas. “But when you look at the Kunstmuseum’s collection, like in every collection, there are gaps,” he says. The exhibition includes the museum’s recent acquisition, Rondo (1971).

Gilliam was very involved in hanging the show. “These works are a little bit site-specific, and what I find more interesting is that they are kind of time-specific,” Helfenstein says. “Depending on the space and the place and the moment, they need to be almost performed—you don’t just hang them like most paintings.”

“It is historically very important to document what he says about the work and to learn how it was intended, as it has not been shown for decades now,” Helfenstein says. “As a curator you have a certain space to interpret things, but it’s up to you—because at a certain point he won’t be around anymore—to show this in a responsible and ideal way. There is also something very generous about it—in a way it’s like the jazz of the time.”

• The Music of Colour: Sam Gilliam, 1967-73, Kunstmuseum Basel, until 30 September

Sam Gilliam’s Untitled (2018) at Unlimited, Art Basel Photo: www.david-owens.co.uk

Gilliam at Unlimited

Gilliam is also showing a new large-scale work, Untitled (2018), in the Unlimited section of Art Basel with Los Angeles’s David Kordansky Gallery. “Gilliam is one of the most important US artists of his generation. It is long due that he gets more international presence,” says Unlimited’s curator Gianni Jetzer, adding that he is “thrilled” that Claude Viallat—who was a key member of the Supports/Surfaces group and is “another master of staging painting as three-dimensional installation art”—is also appearing in this year’s Unlimited. “The French and the American artist are the same age and for me they are soulmates with different backgrounds and origins,” Jetzer says.