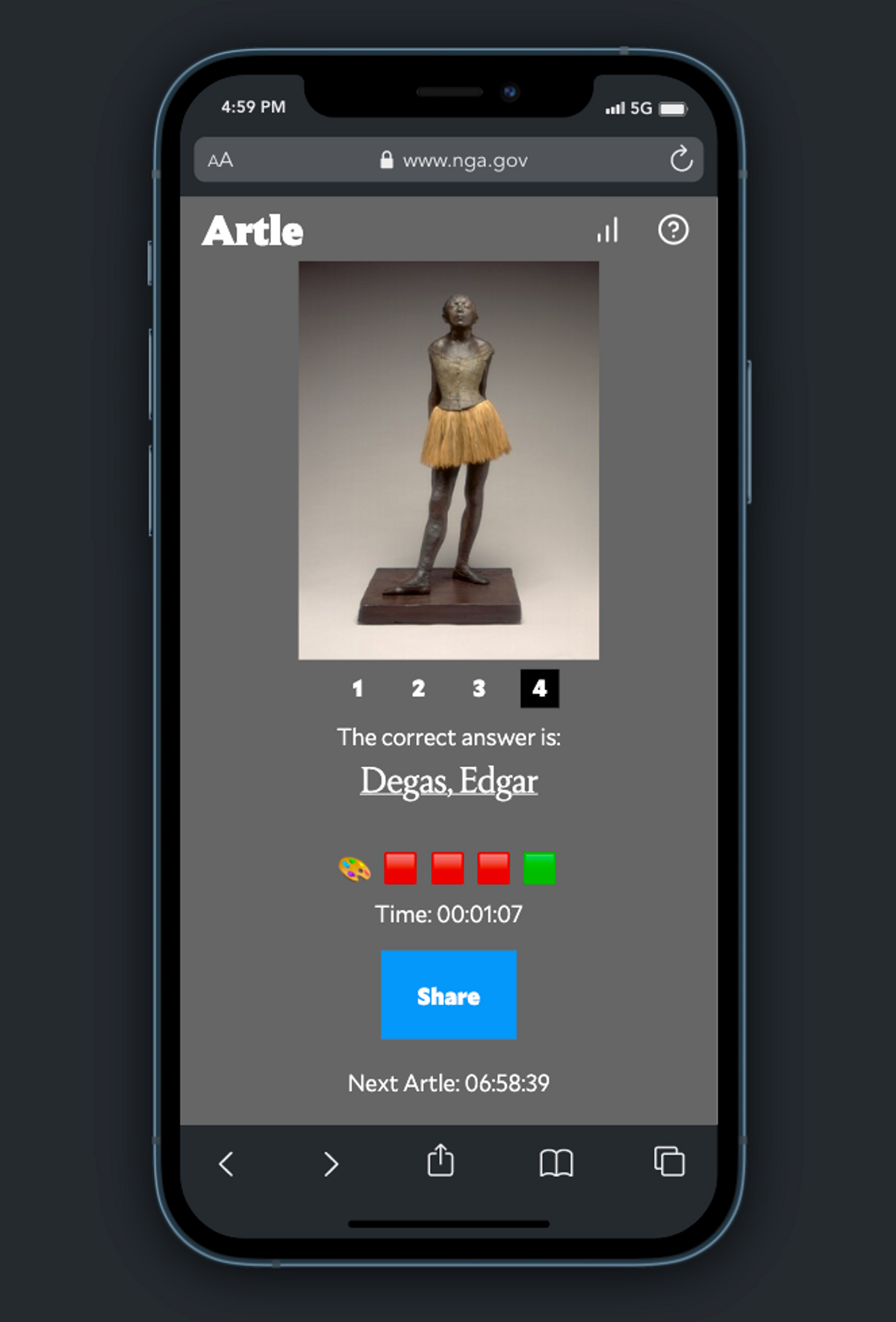

Do you ever miss art history class? Specifically the slide quizzes, when you had to identify famous (and not-so-famous) paintings, sculptures, drawings, and photographs? If so, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC has just the thing—Artle, an online guessing game similar to Wordle, except, as the name suggests, with art instead of words.

Like its famous predecessor, Artle is fairly straightforward. The goal is to guess the artist (no need to memorize French-language titles, media, or years like in school) based on images of works from the museum’s vast collection. The first image that pops up is usually a lesser known or early work, and if you guess wrong, it goes to the next, slightly more famous work, and so on for four total guesses. For example, in a recent game featuring works by Henri Rousseau, the first image was of a print depicting war, the second a painting of a young boy, and only after those did the artist’s renowned jungle scenes appear.

Steven Garbarino, senior product manager at the National Gallery, says the idea for Artle came about during the museum staff’s first week back in the office this spring. “We were trying to think of more ways to inject a little bit of fun into the life of the museum,” he says. Everyone loved the idea and quickly began working on it. It took only five weeks to get it all set up and launched. “Artle is not hyper-complicated technically, but for a museum built by the federal government, five weeks is incredible,” Garbarino says, adding that this was in no small part due to the fact that “every single person in the institution was excited about it.”

According to Garbarino, the most difficult aspect of creating the game was deciding which artists and works to include, and in what order. “We worked with the education department to find art that’s challenging, accessible, and educational,” he says. “We did difficulty tests too.”

Although people can (and do) use their Artle scores to show off their art history knowledge on social media, the game’s true goal is to introduce them to the museum’s collection. When you finish playing the game, names of the works and artists are shown and links to their pages on the National Gallery’s website provide a deeper dive for those interested in learning more. Garbarino says that when the Artle artist of the day was Emma Amos, there was a low “success rate” in terms of people guessing her name correctly, but a lot of players clicked the links after losing the game to read about her and her work. Artle is different from other games, Garbarino says, in that it provides “an opportunity to learn.”

It seems people truly enjoy learning from Artle. When the game was introduced to the public in early May, Garbarino says about 3,500 people played it on the first day. A week later, that number had already increased tenfold.

As for the future of Artle, Garbarino thinks it’d be great to cross-promote the game with other museums and their collections, or include images of painting x-rays or other behind-the-scenes images as one of the four clues. “At some point, the daily guessing-game trend is going to die down,” Garbarino says, “but I hope what we did accomplish was creating a long-term educational tool.” He says he has even gotten emails from teachers about the game. Soon, it seems Artle will be back in the art history classes that helped inspire it.