The Melbourne-based Wurundjeri Corporation hopes to crowdfund $175,000 to secure the return of two never-before-seen works by William Barak destined for auction at Sotheby’s New York today. But, with a combined estimate in excess of $425,000, it seems unlikely their bid will be successful.

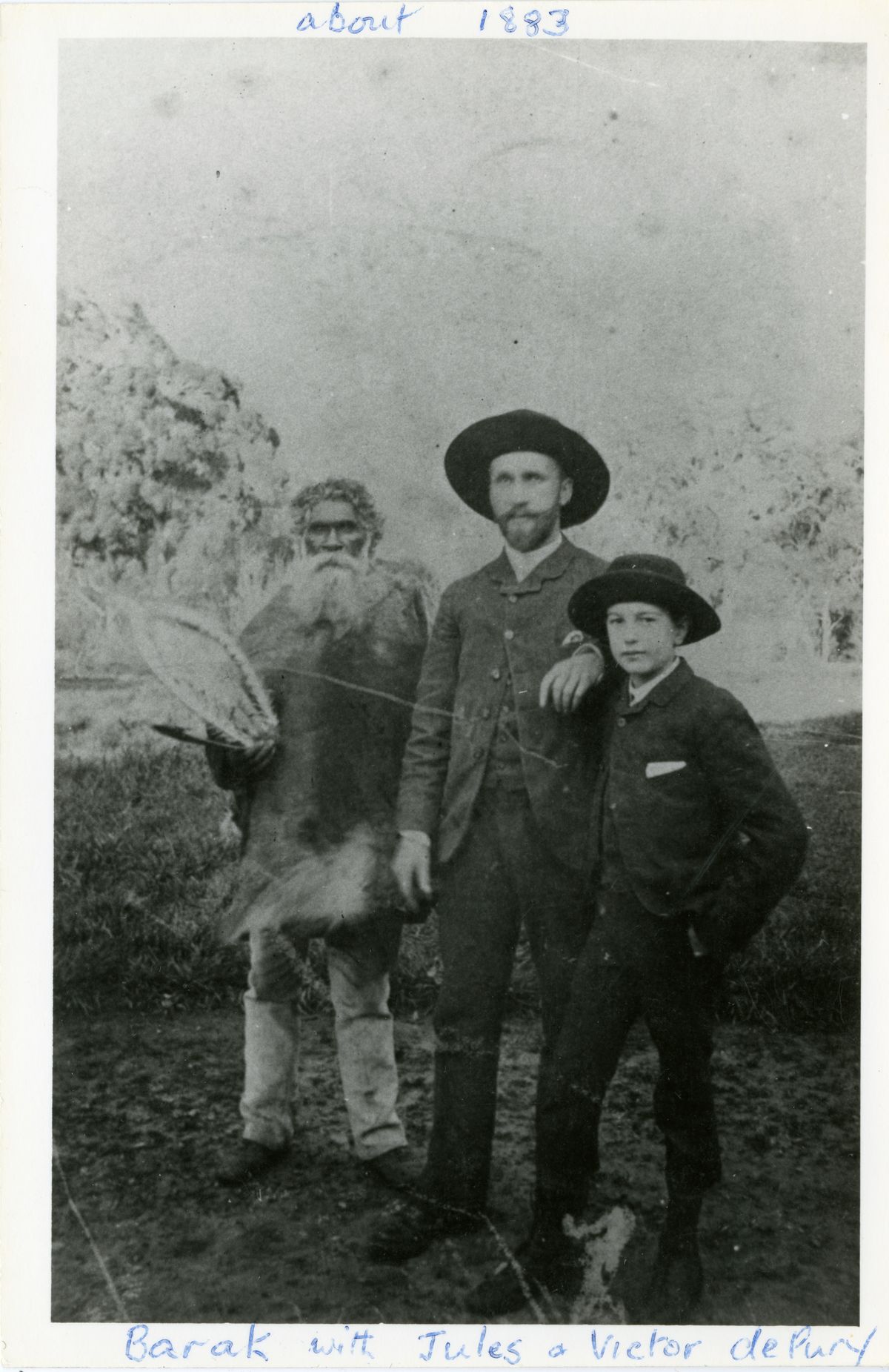

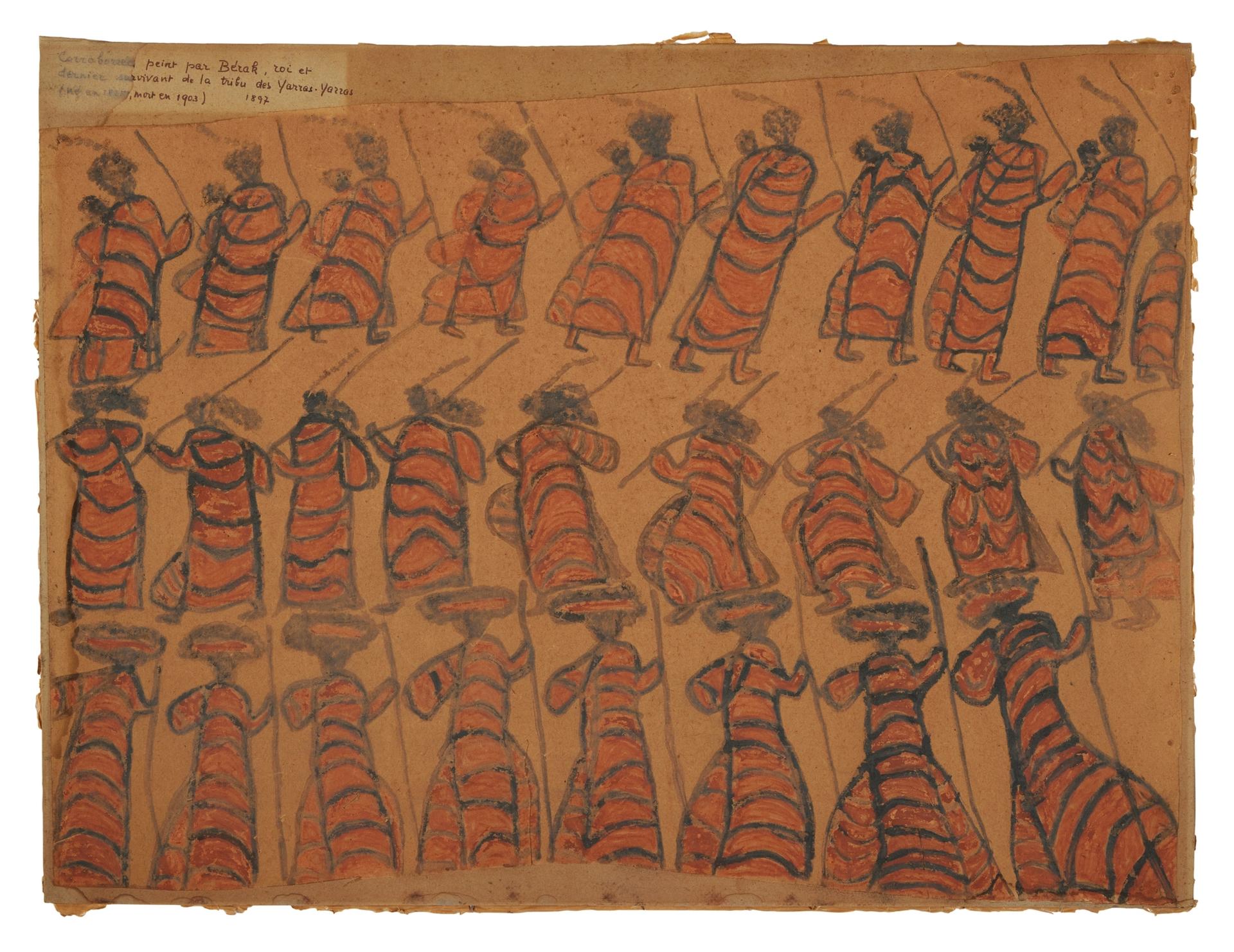

Corroboree (Women in possum skin cloaks) (1897; est $300,000-$400,000), an ochre and charcoal drawing on paper, and Parrying Shield (1897; est $15,000-$25,000), a hardwood shield engraved with traditional patterns, are previously unknown works that resurfaced in Geneva in 2017 following the death of Pascal de Pury, the great grandson of Jules de Pury, the cousin of a Swiss wine-growing family and Barak’s neighbours during his time at Coranderrk Aboriginal Station, 50km east of Melbourne, the capital of Victoria.

Sotheby’s confirms that the two Barak works have been consigned by the descendants of the De Pury family, who include the Swiss auctioneer, art dealer and collector, Simon de Pury. He declined to comment for this article.

Corroboree (Women in possum skin cloaks) (1897) is estimated to sell for $300,000-$400,000

Barak is arguably one of the most significant Australian Aboriginal figures of the 19th century, and one of a handful of recorded artists. Born before the arrival of white settlers in Victoria, Barak experienced firsthand the devastation of colonialisation and the destruction of a traditional way of life. As a young man he witnessed the signing of a disputed treaty between local clan leaders and John Batman, an opportunistic grazier and explorer, who murdered three Tasmanian Aborigines, before expanding his pastoral interests to Victoria.

In 1863, Barak helped establish Coranderrk as a self-sustaining farm run by Aboriginal people. And when the colony introduced legislation prohibiting Aboriginal people from performing traditional ceremonies and speaking in their language, Barak took up painting. Producing 52 paintings in his lifetime, possibly more.

Barak “used his artwork to preserve cultural practices and knowledge”, Nikita Vanderbyl, an art historian and Barak scholar, tells The Art Newspaper. “They’re filled with indigenous knowledge.” Barak’s works are amongst the oldest of 103 items in an auction that spans spears, shields and baskets to “Western Desert” masterpieces by the late Mick Namarari and Emily Kame Kngwarreye, as well as contemporary works by Vernon Ah Khee and Richard Bell.

The auction is part of Sotheby’s “marquee month” in New York and is drawn from a variety of sources including the Steve Martin and Anne Stringfield collection, the estate of James Wolfensohn, the former head of the World Bank and The Thomas Vroom collection.

Barak's Parrying Shield carries a $15,000-$25,000 estimate

When the previously unknown works appeared in Switzerland in 2017, Vanderbyl, knew “pretty strongly” that they would be linked to the De Pury’s.

Jules de Pury acquired the works in 1883 while visiting his cousins at Yeringberg Station, a property still owned by the Australian branch of the De Pury family. When Jules returned to Switzerland, he took them with him.

But Vanderbyl is vexed by the family’s decision to unload Barak’s art at auction—the family has previously donated “quite a number” to the Musée d'Ethnographie Neuchâtel, a museum housed in a building bequeathed by James-Ferdinand de Pury in 1904. “I am just as curious as everyone as to why they have chosen to sell,” she says.

Aunty Joy Murphy Wandin, a descendant of Barak believes the works were entrusted to the De Pury family “in exchange for cultural knowledge and safety of their place on Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung country”. With the forthcoming auction, “Aboriginal cultural lore has been breached”, she says in a statement.

A spokesman for Sotheby’s says: “We have been in open dialogue with the corporation for many weeks now in order to ensure they are able to participate in a fair and open bidding process. Barak himself was an early pioneer in creating a market for his work, which he gifted to friends and sold to visitors of his community, and was a noted champion and advocate for his culture to the widest possible audience. As a leader, diplomat, and advocate for his people, Barak forged many close relationships beyond his immediate community, and these works embody that spirit of cultural dialogue and the preservation of their cultural history.”

Nonetheless, the scarcity of Barak’s art has increased its value at auction and further distanced it from his descendants. In 2016, the Wurundjeri Corporation ran a similar campaign when another previously unknown painting resurfaced at Bonhams auctions in Sydney. At the time they raised $38,000, well short of the $362,000 sale price. The result was made worse when the private collector refused the community access to view the work in person. They hold out hope this time things will be different.