A recurring motif of urban Haitian art is the skull, whether hammered from stone like the rough heads of Ti Pelin (Jean Salomon Horace), or actual crania atop assemblages of found materials by members of the group Atis Rezistans. If the Caribbean ever wanted a salon des refusés, Haiti’s capital Port-au-Prince was the place for it. As other world crises eclipse the deadly anarchy and poverty of Haiti, the dramatic and grotesque work featured in Pòtoprens: The Urban Artists of Port-au-Prince (Atis Nan Vil Pòtoprens in Creole) is a reminder that in Haiti, so far, art survives almost everything but also exposes the gaping wounds.

Pòtoprens is the catalogue of the 2018 exhibition, which showed more than 25 artists at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn, New York. If naming Haiti’s capital in the title is crucial, so too is the inclusion of the full text in Haitian Creole. These are urban artists, often working with materials scavenged on city streets (plus body parts). Artists of earlier generations, labelled naif, drew, painted or carved folkloric scenes from the countryside, mostly feeding the tourist trade, now gone. The show then travelled—as it arrived, in a shipping container—to Miami, which over the years has become Haiti’s shadow cultural capital.

With an ominous and elegant black cover, this fully illustrated volume is an essential guide to what the show’s co-organiser, Leah Gordon, calls “the art of the majority urban poor”. Haiti urbanised quickly from the 1960s to the 1980s and the rural people brought with them fierce attachments to vodou. In Pòtoprens, more of that context comes via a detailed illustrated timeline.

Turning point

If modern Haitian art had a crucial turning point, it was the formation around 2007 of Atis Rezistans (Artists’ Resistance), a group that included woodcarvers who gathered autoparts and other debris to assemble figures—transgressive, fearsome, often satirical, sometimes wildly erotic—that shattered any settled notion of “arte povera”. This art from the urban streets, literally, is at the core of Pòtoprens, with artists bringing their own signature elements to these sculptural collages: skulls (Andre Eugene), dolls’ heads (Katelyne Alexis), tyres and wood (Celeur Jean Herard).

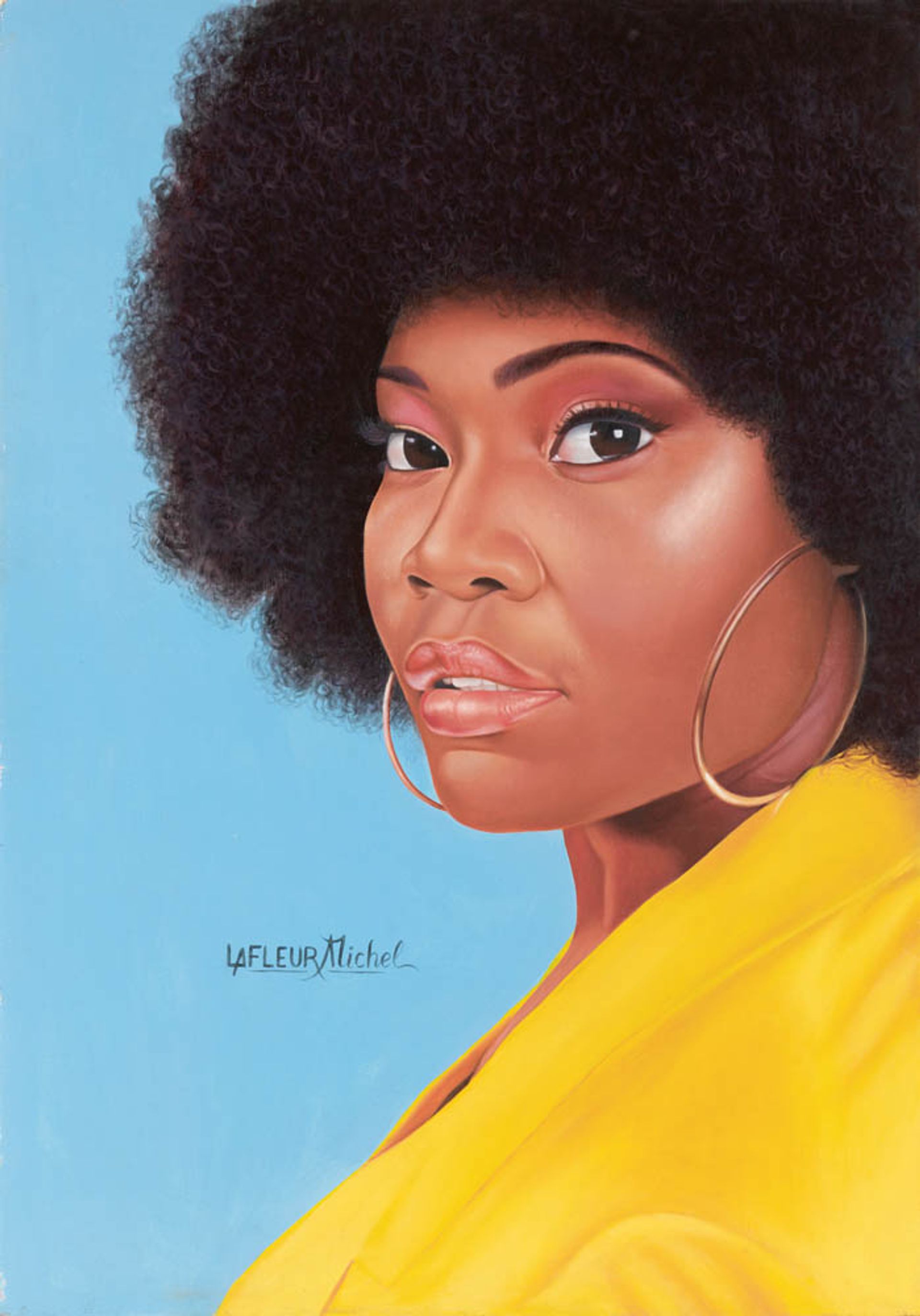

Michel Lafleur’s Rutshelle Guillaume (2018) was created as a billboard advertisement Photo: Daniel Bradica, courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works

In 2009, the group created the Ghetto Biennale, which, like their work, offered an alternative to pricey and commercial Art Basel in Miami Beach. That work formed the core of Pòtoprens in 2018 and much more. Grimacing skulls by Ti Pelin are of rock once found in local streams. Vodou flags, stunning sequinned sewn compositions by the former wedding dress seamstress Myrlande Constant—daughter of a vodou priest—are visions born of the practice of flying flags at vodou temples. One of two women featured in Pòtoprens, Constant is now represented by Fort Gansevoort in New York.

Closest to conventional painting (and to Pop art) are huge portraits for barbershops and beauticians by Michel Lafleur, billboarding the results that lure customers. The catalogue documents the building of a barbershop for the exhibition that Lafleur, denied a US visa to visit, decorated with his self-portrait.

Like any show of contemporary art, Pòtoprens of 2018 has been overtaken by events. After its president’s assassination last July, Haiti has been anarchic, unsafe and unvisitable. Yet new generations of Atis Rezistans still work and the group will be represented at documenta in Kassel, Germany this summer. We won’t have another catalogue (or show) like Pòtoprens until the shipping container sails again, which won’t be any time soon.

Edited by Leah Gordon and Joshua Jelly-Schapiro, Pòtoprens: The Urban Artists of Port-au-Prince, Pioneer Works Press, 416pp, colour & b/w illustrations, $55 (hb), published 19 March

• David D’Arcy is a correspondent for The Art Newspaper in New York