When David Shrigley was asked to create a work for a semi-circular swimming pool at Brighton Beach House, Soho House’s latest outpost on the south coast of England, the design was, he says, a “no-brainer”. As he puts it: “It’s an arc, so what’s it going to be? A banana. It can’t really be a cucumber as they are not bendy enough.”

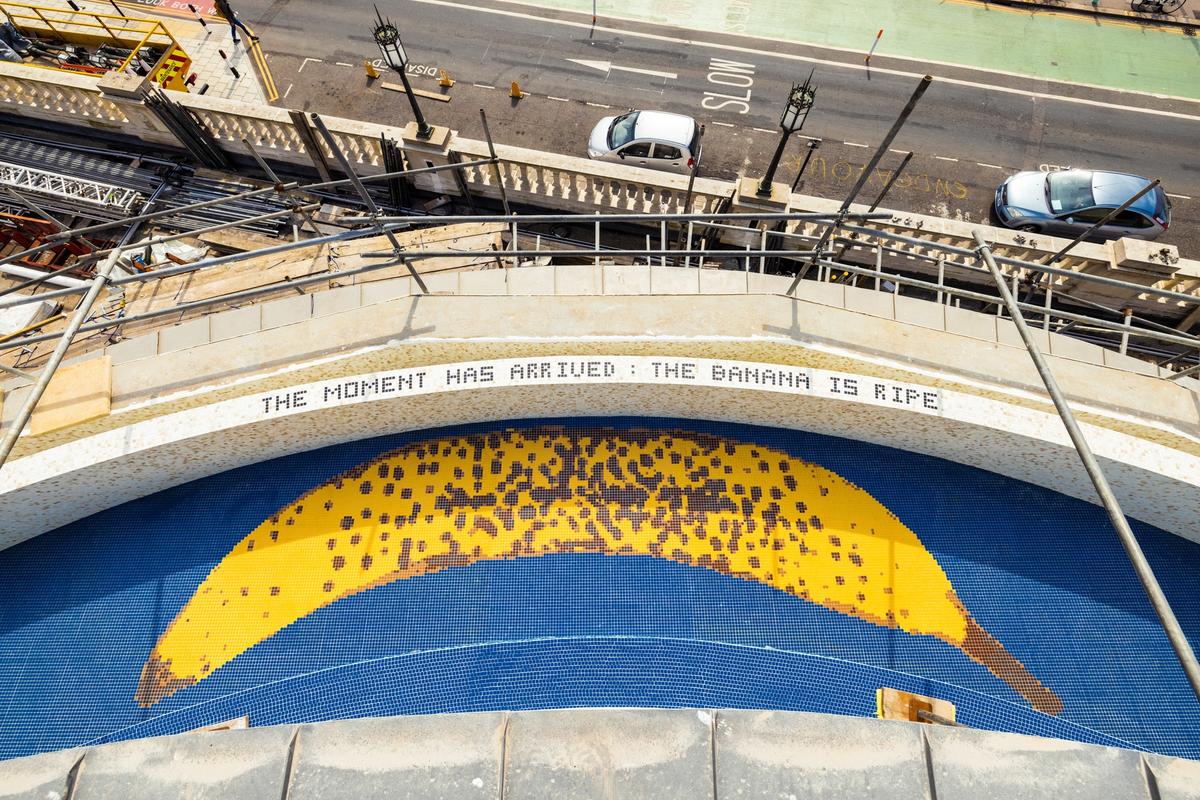

The banana, rendered in bright yellow mosaic tiles with splodges of brown, curls round the bottom of the pool, which overlooks the seafront to the east of Brighton pier where the area known as Kemp Town begins. Around the rim of the pool are the words: “The moment has arrived the banana is ripe”.

The design is taken from a painting Shrigely created last year. But, he says, “an over-ripe banana, with its decadent sweetness, is a metaphor for Kemptown. The banana is one of those ones that you’ve had in your ruck sack all day… it tastes good, it’s the perfect banana. But you don’t want to leave it there any longer. Eat it now.”

David Shrigley has lived in Brighton since 2015. © Grace Difford

Having lived in Glasgow for 27 years, Shrigley moved to Brighton in 2015. The sea was a big pull (Shrigely prefers swimming in the sea to pools), as was the relatively mild weather. “There’s a real odd charm about Brighton,” he says. “It’s sort of a city but then it’s also a funny seaside town. It has a lot of unique qualities, I’ve always liked it here.”

Shrigley has a studio in Kemptown, in a disused church on the corner of the road he used to live on. He is currently looking to buy a home in Hove, though the opening of Brighton Beach House is giving him pause for thought about staying in Kemptown, which is considered the more bohemian part of Brighton and has a large homeless population.

“You take the rough with the smooth in Kemptown,” Shrigley says, recounting an interview he did with the Observer newspaper in 2018 in which he described the area as “full of dogshit and lunatics”—referring not to homeless people, but instead to “genuinely mad people, barking at the moon, who live in houses and who are mad”.

He continues: “I was on the front page of the Brighton Argus with that quote. I was mortified. At the time, I was the guest director of the Brighton Festival and the Argus tried to interview people after one of my performances, trying to get them to say how awful what I said was. But people were just like, that’s what Kemptown is like. They wanted it to be a feeding frenzy, to make out that I’m some rich arsehole that doesn’t care about Brighton and Hove.”

That couldn’t be less true. Shrigley is a patron of Phoenix Art Gallery, an exhibition space with 100 affordable artist studios which opened with charitable status in the centre of Brighton in 1995. “The fact they have managed to withstand temptation from property developers is an achievement in itself,” Shrigley says. “The exhibition space is great, it’s just about trying to find a way to make it work sustainably.”

As with Soho House’s other venues, the backbone of Brighton Beach House is its local art collection. Kate Bryan, Soho House’s global head of art collections, discovered several artists through Phoenix Art Gallery, among them Miranda Forrester, who has designed the fabrics used throughout the club, including the parasols on the terrace of Cecconi’s Italian restaurant, which opened at the end of April ahead of the club’s full launch later this month.

Other artists who were born, based or trained in and around Brighton and whose works have been acquired for the 110-strong collection include Rachel Whiteread, Dexter Dalwood, Somaya Critchlow, Dee Ferris, Harold Offeh, Magali Reus and Aimee Parrot, who has created a mural on the walls of the lobby. Tania Kovats, meanwhile, has collected water from the sea in Brighton and displayed it in bottles of various sizes at the entrance to the club.

Print from Isaac Julien's Looking for Langston film series (1989). Courtesy of the artist

The overwhelming majority of these artists, Bryan says, are “transient, in the sense they move in and out of Brighton”. She adds: “Some were born here or studied here, but now they are in London because, even though London is incredibly expensive, there’s more choice when it comes to studio space. I often hear artists saying they want to move back to Brighton—but studios are at a premium.”

Shrigley agrees: “When I moved here I felt the art scene was much more about graphic art than it was about fine art. There was a lot of street art, and the reason for that is that you don’t necessarily need a studio to be a graphic artist. It’s a challenge to have a studio and that’s reflected in what artists do in Brighton.”

Works by 50 LGBTQIA+ artists have also been acquired for the Beacon Collection, which has been put together by the curator Gemma Rolls-Bentley and is the largest collection of queer art to be permanently on display in the UK. “The reason I called it the Brighton Beacon Collection was because of this idea of Brighton being somewhere that people from the LGBTQIA+ community is drawn to. It’s a real safe haven,” Rolls-Bentley says.

Some artists created new works “thinking about coastal locations such as San Francisco, which have historically attracted the queer community”, Rolls-Bentley says, while others contributed existing or historical pieces.

Isaac Julien has donated a print from his Looking for Langston series, while Catherine Opie has given a large-scale chromogenic print, Pig Pen (1993). Maggie Hambling has gifted a portrait of Oscar Wilde she painted decades ago but never sold, choosing instead to keep it in her studio. “As a painting of a queer icon, it was just perfect,” Rolls-Bentley says.

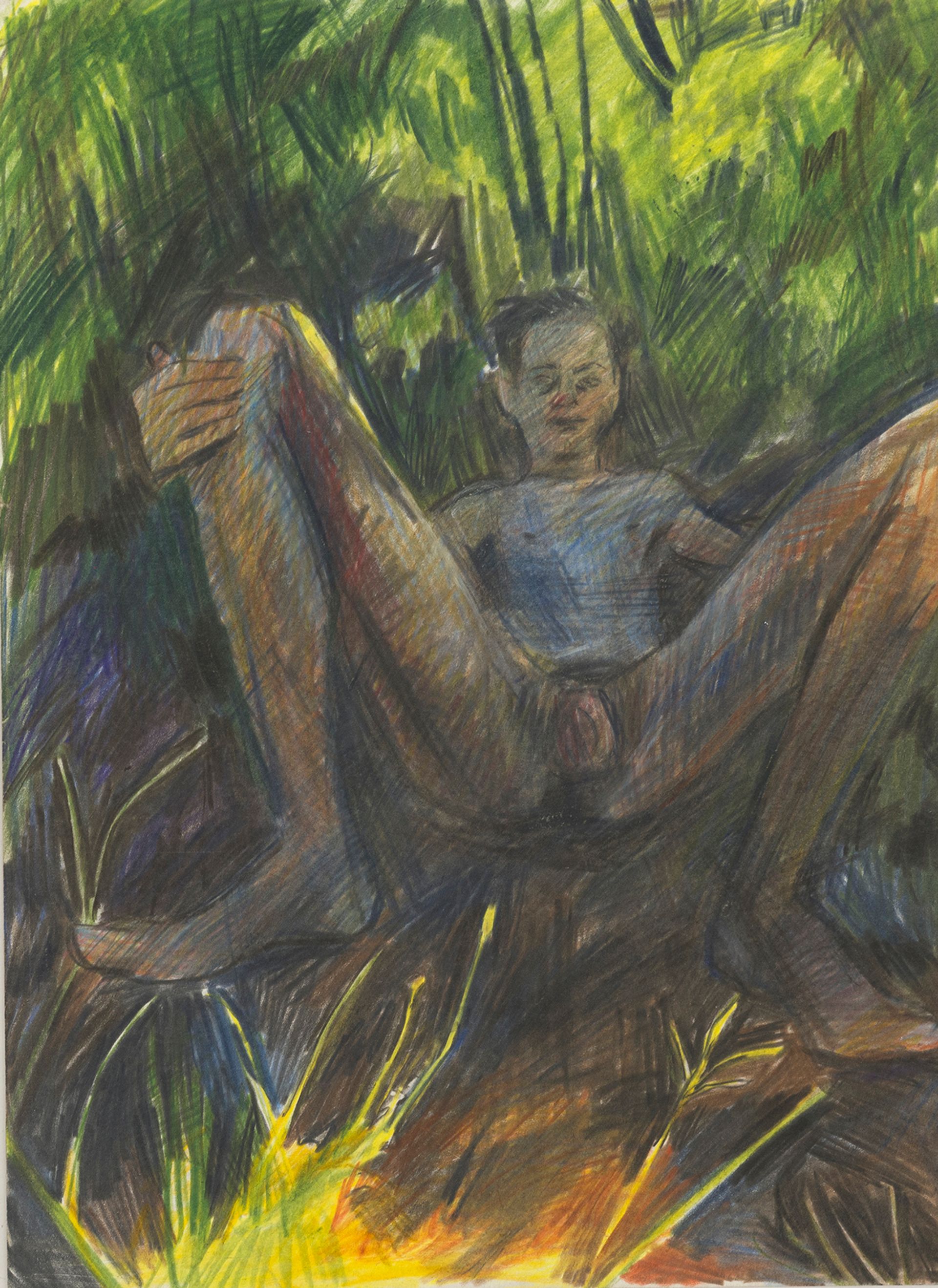

Jake Grewal's Sweet Golden Kisses (2021). Courtesy of the artist

Archival works come courtesy of artists including Wolfgang Tillmans, who donated a poster he designed for the Gay Games in Amsterdam in 1990, while E-J Scott, who founded the Museum of Transology in Brighton in 2017, gifted an activist placard that reads “Transition now, I’ll show you how”. Among those to donate new works are Jake Grewal, Christina Quarles and the artist duo Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings.

Building the collection has been a “really moving experience”, Rolls-Bentley says. “There have been so many studio visits where myself and the artists are both in tears as we’re talking about the importance of queer representation and how we just didn’t grow up with that in art.”

Though Brighton Beach House is a private members’ club, Bryan is intent on opening up the collection to the public, via a website with dedicated content, as well as the talks programme. Students can also book tours. As she says: “We want people to be able to come in and see the art—that will be an important legacy of the Brighton Beacon collection.”