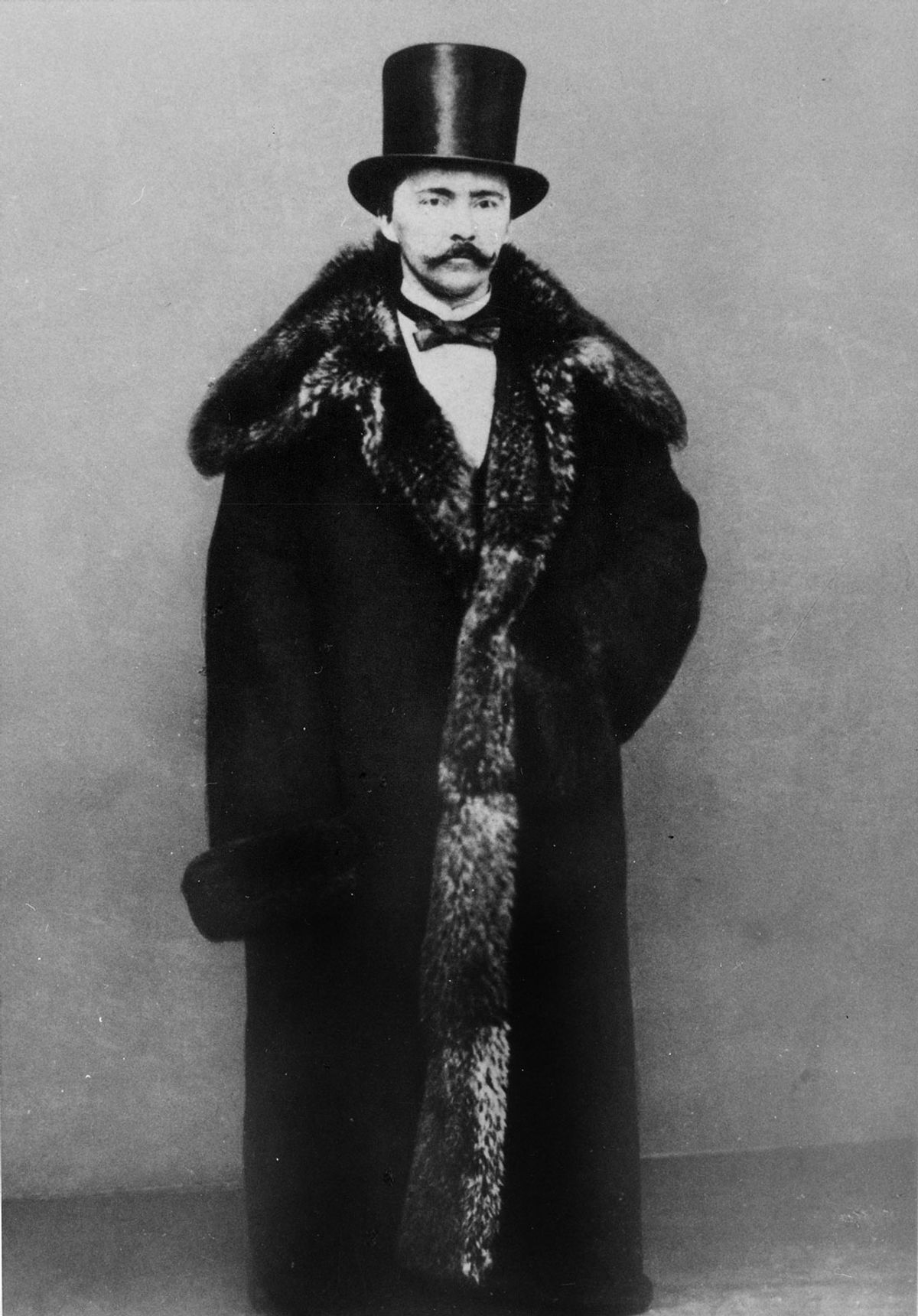

Merchant, adventurer, linguist, and spinner of tall tales, banker in the California gold rush and military contractor to the Russian army during the Crimean war—by any measure, Heinrich Schliemann lived an extraordinary life. And that was even before Schliemann, in his late 40s, embarked on the endeavour that was to make him world famous: the excavation of Hisarlik, an ancient settlement in Turkey now accepted as the site of Homer’s legendary city of Troy.

To mark the 200th anniversary of Schliemann’s birth in 1822 in the north German state of Mecklenburg (then a duchy in the German confederation that was established following the defeat of Napoleon), Berlin’s Museum of Prehistory and Early History, which holds a considerable amount of Schliemann’s collection, is mounting an exhibition dedicated to him at the James-Simon-Galerie and Neues Museum.

An owl-headed vessel from Troy © State Museums in Berlin, Museum of Prehistory and Early History / C. Plamp

Matthias Wemhoff, the director of the museum and project manager of Schliemann’s Worlds, is clear that the show’s intention is restore Schliemann’s reputation, not only as a pioneering archaeologist but as an exceptional figure in his own right. “We want to show his whole life, not just look at the archaeology. If you understand the first half of his life you understand much better how he is as an archaeologist,” Wemhoff says. “He was a tradesman, a self-made man, and a person who used all possibilities of the 19th century. He travelled across so much of the world, in a way that was possible for the first time in history. He had no fear. That’s the important characteristic.”

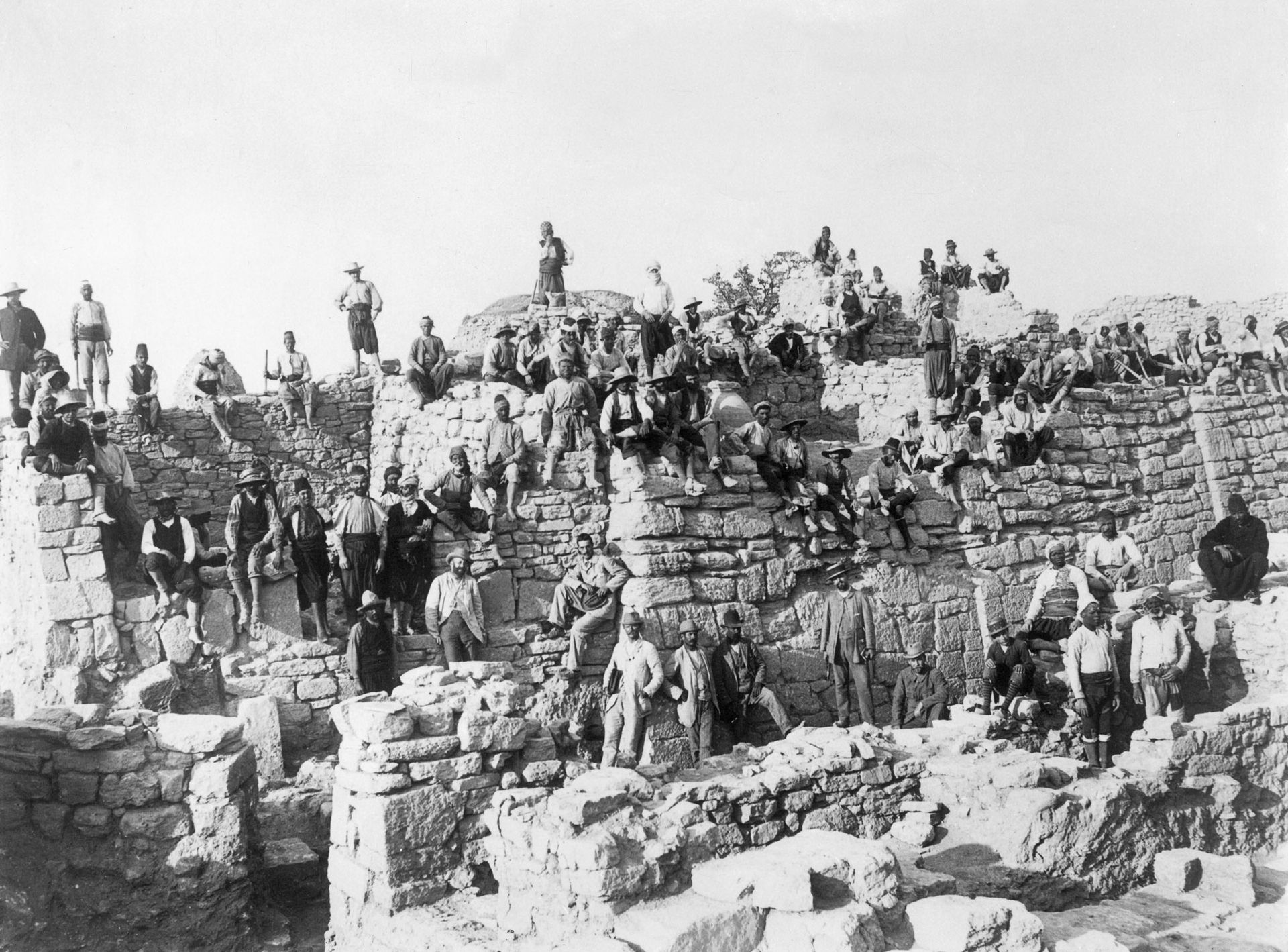

Since his death, Schliemann’s reputation has suffered considerably, partly from his reputation for embellishing many of the stories about himself, his lack of academic rigour, and his rudimentary archaeological techniques—most notoriously the giant trench he dug in his first Hisarlik excavation in the 1870s, which is now thought to have obliterated much of the Trojan archaeology he was looking for. But Wemhoff defends his man, suggesting that Schliemann pioneered the use of stratigraphy—the study of archaeological layers—as well as studying the age of ceramics to date the layers. Wemhoff says the Schliemann Trench, as it is now called, was not simple vandalism but was in fact due to the type of archaeology that Schliemann encountered in northern Germany, where large barrows were excavated by tunnelling through it to the base to locate a grave.

Excavation team in Troy in the 1890s © bpk

Schliemann famously found a collection of gold artefacts—called Priam’s Treasure, after the mythical king of Troy—which will not, unfortunately, be on show in Berlin. The hoard was removed by the Soviet army from its hiding place in Berlin in 1945, secretly taken to Moscow and only in 1994 did the Pushkin Museum admit to its whereabouts. Wemhoff says his museum had planned to tour their exhibition to Russia so that Berlin’s collection could be reunited with the Pushkin’s, at least temporarily. But in the current geopolitical situation, all that is off.

In the end, though, the show is about showing off Schliemann’s scientific commitment. Wemhoff points out that, after finding the Priam artefacts. Schliemann persisted in working at Hisarlik for two decades, refining and improving his practice. Wemhoff adds: “He’s much more than digger after gold.”

• Schliemann’s Worlds, James-Simon-Galerie and Neues Museum, Berlin, 13 May-6 November