One of the biggest controversies in the art world in 2020—a year not devoid of drama—was the surprise postponement of a sweeping survey of the Canadian-American artist Philip Guston (1913-80), which was set to tour four major museums in the US and UK.

Philip Guston Now was originally due to open in June 2020 at Washington, DC’s National Gallery of Art, before travelling to the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) Houston, London’s Tate Modern and finally the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) Boston in autumn 2021. After understandably announcing an eight-month Covid-related delay that summer, the four museums proceeded to baffle—and even outrage—a large swath of the art establishment by announcing that they were holding off on the opening until 2024.

Deferring obliquely in their joint press release that September to everything from the Black Lives Matter movement to the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police, the museums were apparently trying to figure out a way to protect museum-goers—in a heated political and social environment—from Guston’s already well-known visual references to the Ku Klux Klan. Spread out over some two dozen works, the exact number of which would have varied at each venue, Guston’s complex Klan imagery has been construed by critics and admirers as part of the artist’s larger interest in masks and disguises of all kinds, and the motif dates back to his early, socially conscious mural period of the 1930s.

Guston's Couple in Bed (1977) © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth; image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago and MFA Boston

A few months after announcing their decision, the museums added self-injury to the perceived insult of the art world by rescheduling the rescheduling, moving the dates of the show again, this time to start in 2022. That show—with the same title and largely similar checklists, but with a bulwark of new curatorial and extra-curatorial input—will begin its four-venue tour on 1 May, with the original final stop in Boston recast as the first.

The MFA Boston version has undergone a dramatic redesign, relying now on thematic as well as chronological groupings. And the official list of curators has grown from one—the New York art historian and Guston scholar, Kate Nesin—to four, including Ethan Lasser, brought to the museum in 2019 to oversee its entire collection from both North and South America, and Terence Washington, an art historian and curator. Washington came to the museum’s attention in autumn 2020, he says, after he participated in an online forum addressing the lingering Guston controversy, in which he spoke out against institutional racism in the museum world.

The Boston show, with 73 paintings and 27 drawings, will be a fraction of the size of what the National Gallery of Art is planning for its more definitive version, in which some 250 Guston works will be spread out among two related shows. But it will nonetheless present a thorough overview of the artist’s decades-long progression from leftist realist to aesthetically minded Abstract Expressionist, culminating in his fateful re-emergence in the 1960s as a darkly humorous, visual polymath, whose equivocal works—connected to identity and mortality, as well as social justice—are now valued as his signature achievement.

Guston's Gladiators (1940) © Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. © Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Significant loans include Gladiators (1940), a figurative depiction of children fighting, and Red Painting (1950), a textured abstract from a decade later. In a very late work, Couple in Bed (1977), painted a few years before his death in 1980 aged 66, Guston creates a dual portrait of himself and his wife, who became debilitated around that time, shown with their faces obscured; the white sheet of his Klan imagery appears here as a kind of shared hospital gown, a death shroud to-be.

Some critics of the postponement viewed the delay as the latest example of cancel culture. Matthew Teitelbaum, the director at MFA Boston, refutes the censorship charge and argues that the postponement has allowed his own museum to “think more strategically about the ways in which audiences will relate to the work”. However, of the original 15 Klan-related works planned for Boston, five have been removed, including two large and significant paintings from 1970, Caught and Dawn. A museum spokesperson says the decision was made due to “space reasons” and that a new Klan work has been added.

A noticeable change in Boston is the conspicuous repackaging of Guston’s most celebrated Klan work, The Studio (1969), which is regarded as a self-portrait, showing an artist in a sheet painting a figure in a sheet, working on a canvas that recalls a sheet. Originally planned to be displayed along with other works from the period, it will now be contained in a room-within-a-room, suggesting Guston’s own studio.

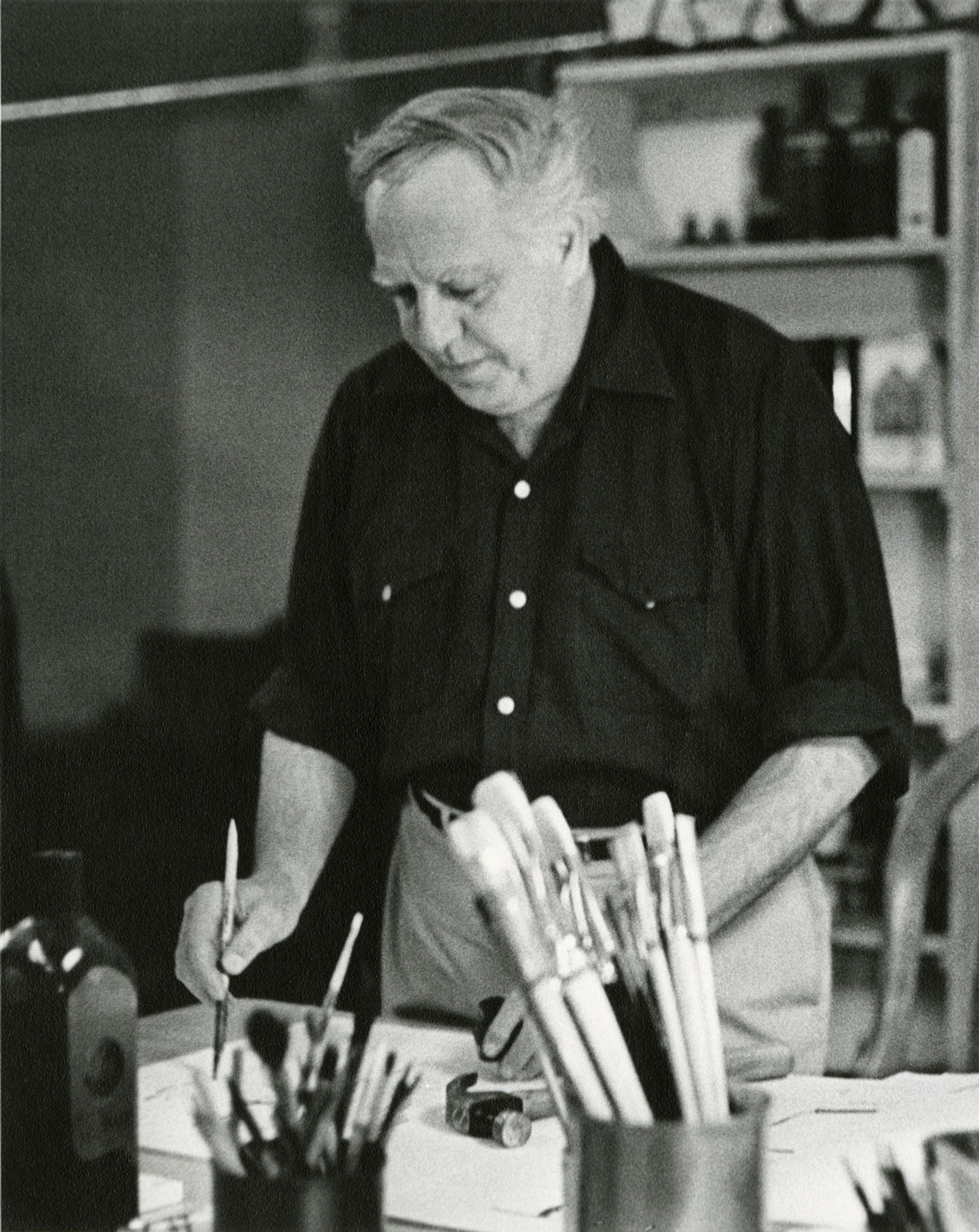

Philip Guston in his studio in 1970 Photo: Frank K. Lloyd, Courtesy of the Guston Foundation and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

According to the lead curator Alison de Lima Greene, MFA Houston will retain the original chronological approach and stick to its original checklist, with minor adjustments. A Tate spokesperson said it was too early to share its updated checklist. The Tate’s original curator, Mark Godfrey, left the museum in March 2021, after his public disagreement with the museum’s decision to postpone the show led to an in-house disciplinary action. He has been replaced on the show by the Tate’s Michael Wellen, a specialist in Latin American art.

Back in Washington, DC, where the idea for the show came about seven years ago, thanks to the curator Harry Cooper, the original checklist remains largely unchanged, with nothing dropped due to content or imagery, while the actual design is a work-in-progress. In another broad expansion of participating voices, the National Gallery is including “a community advisory group of ten individuals” who will help the museum “think about interpretations and layout”, Cooper says.

The National Gallery of Art’s director, Kaywin Feldman, is looking on the bright side. She believes the bad press and ensuing debates about the artist have actually been a net-positive. “The art world renewed their vows with Guston,” she argues, adding that months of heated discussion allowed people “to celebrate his genius and his courage”.

As for the controversy itself? “I would use ‘controversy’ in quotes,” she says. “It was an art-world storm, with little impact with on the general public.” And it is the general public, she says, that will make the show “wildly successful in each venue”.

• Philip Guston Now, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1 May-11 September; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 23 October-15 January 2023; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 26 February-27 August 2023; Tate Modern, London, 3 October 2023-25 February 2024