A Life Spent Painting, a forthcoming biography of Philip Guston (1913-80) by the art historian Robert Storr, separates the US artist’s career into three periods: social realism, Abstract Expressionism and the late playful, figurative style that he is best known for. It is the transition to this final period that is detailed in the extract below. The break with what had come before was seen by some as an uncharacteristic departure. But, as Storr explains, much of the cartoonish base material was there already, harking back to the childhood interests as well as sketches that Guston made in the 1950s of his fellow artists in New York City.

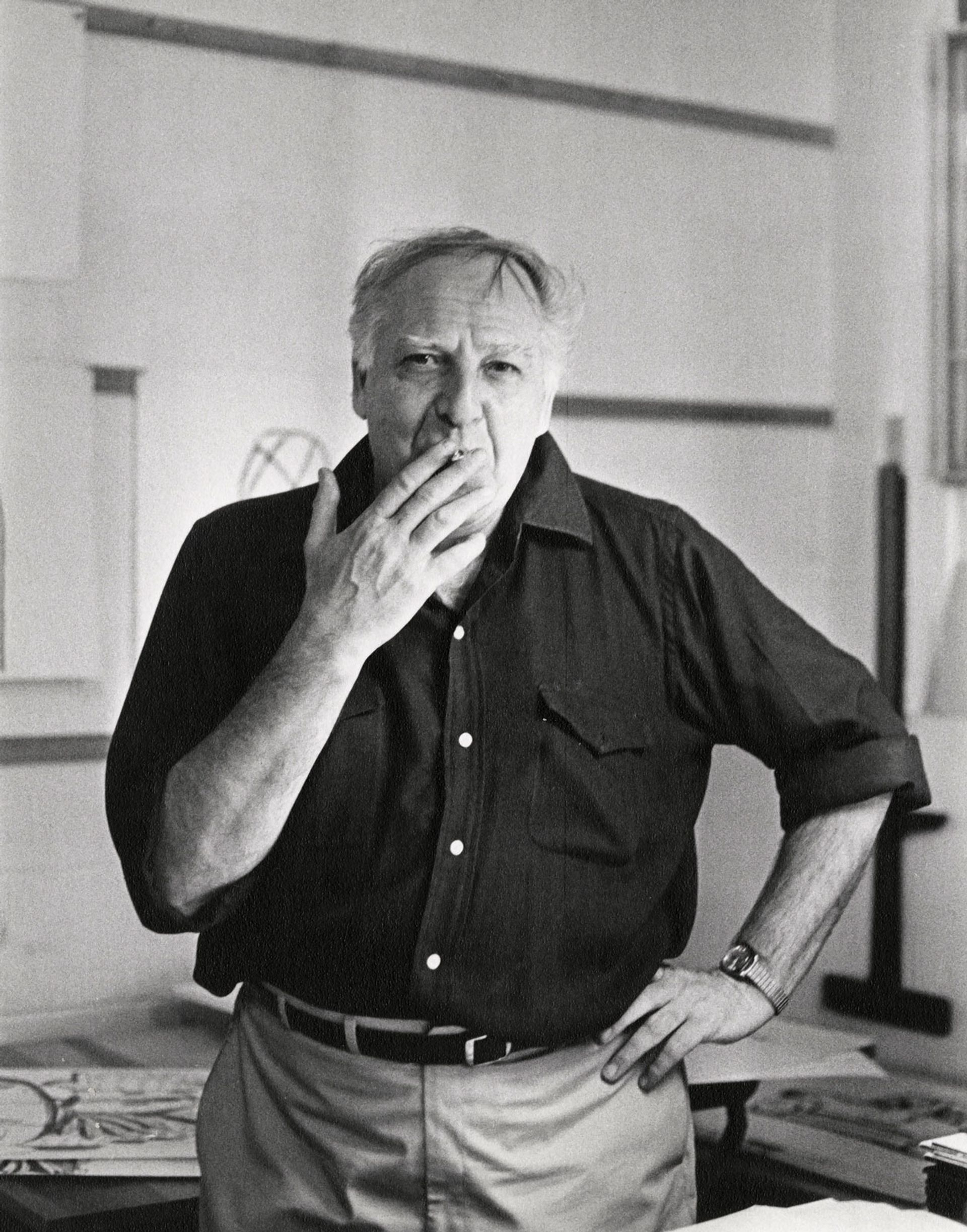

Philip Guston in his Woodstock studio in 1969 Photo: Frank R. Lloyd

The bravura technique deployed in [Guston’s] darkest, heaviest canvases between 1960 and 1964 rehearsed many of the moves he would [later] make, and the imposing contrasts between image and ground [...] but it also recalled his childhood fascination with the “funnies” and his own immature cartooning efforts, plus a number of little-known caricatures of friends he made during the mid-1950s in connection with a large comic scene of a Greenwich Village loft party.

The cast of characters is a Who’s Who of 10th Street Bohemia, including “Bill” and Elaine de Kooning—he in a sailor’s knit cap, she in a flapper’s dress; Harold Rosenberg with caterpillar eyebrows and moustache; Robert Motherwell with rosy round cheeks clutching a cigarette; John Cage with a brush cut/fright wig and wide, hollow Little Orphan Annie eyes; the painter Landes Lewitin as a monolithic, bald, faceless head, aswirl with cryptic signs like the hieroglyphs he used in his paintings; Betty Parsons with an inscrutably “abstract” expression and a page-boy haircut; and, in sweet revenge on Ad Reinhardt’s satirical jibes, a caricature of the notoriously mordant spoiler as a tonsured worm. The significant fact is that when Guston started to make paintings and drawings in the same ludic spirit in 1968, he was playing himself as never before, contrary to the perception of some who chided him for acting “out of character.” The truth was that Guston had been enamoured of cartooning from the very start and had kept his hand in ever since, notably with such intimate mockery of his milieu.

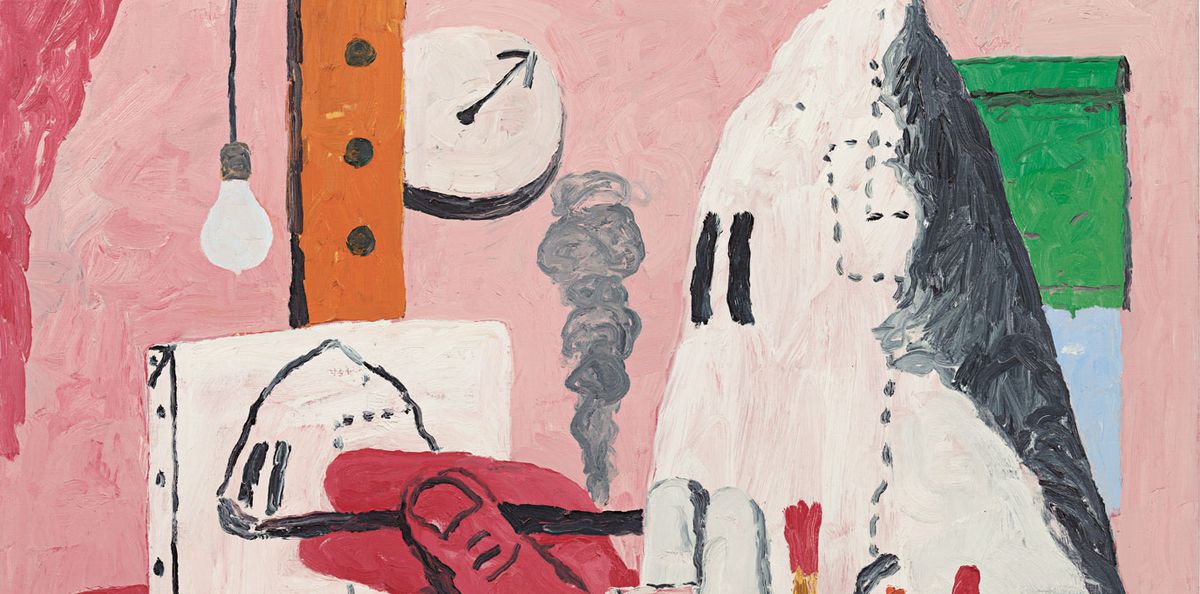

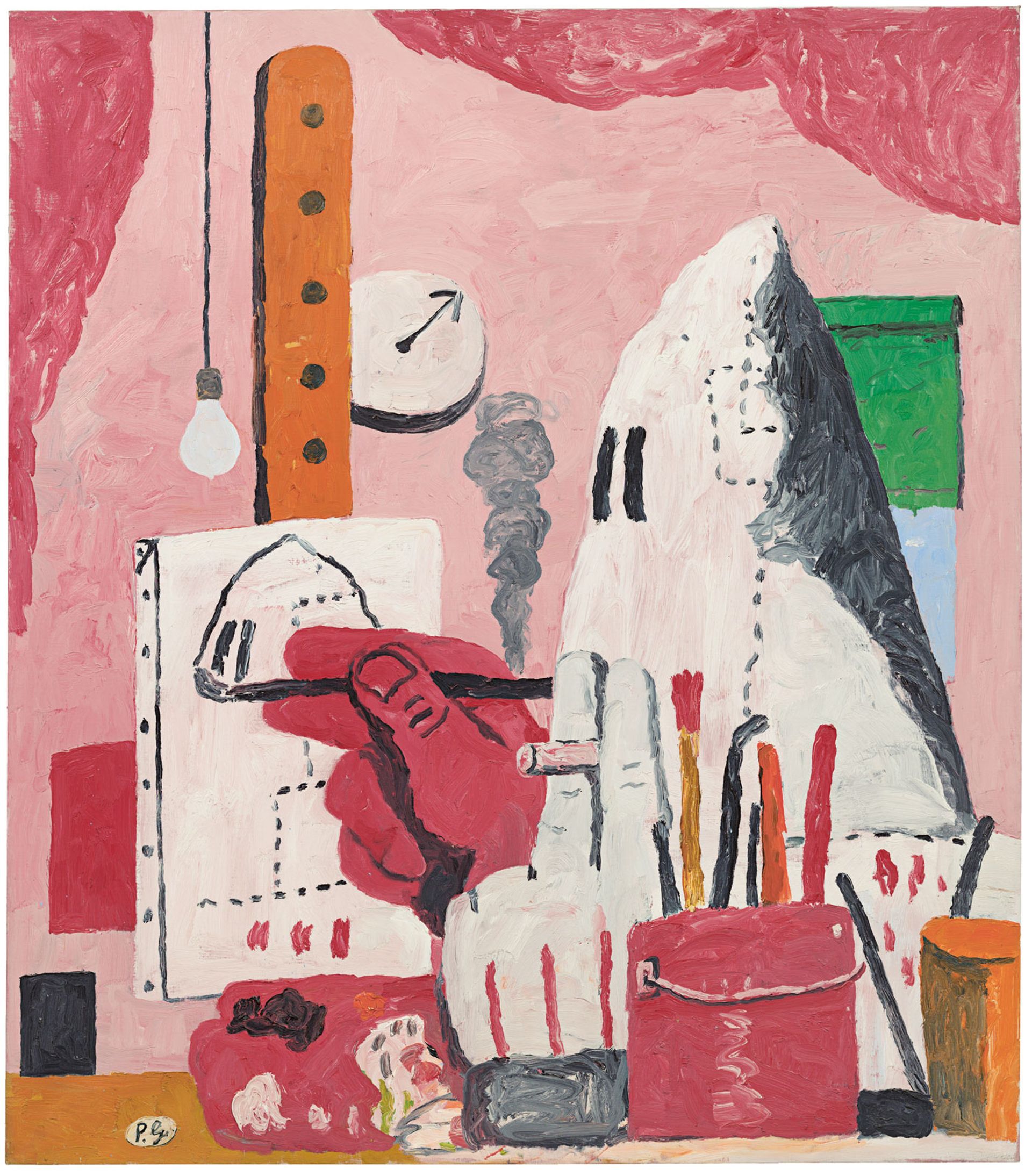

Philip Guston's The Studio (1969) © The Estate of Philip Guston

Commonplace, innocuous things such as books, cars, cups, and clocks abound, as do the tools of his trade, including a reed pen and bottle of ink paradoxically drawn in charcoal. By 1968, Guston had dilated his scope to focus on archetypal modern cities, cartoon paraphrases of work of the 1940s, where a brick wall blocks the view of such cities. Eventually all served as sets and props for a gang of Ku Klux Klansmen straight out of his lynch paintings of the 1930s—photos of which he had kept and pulled out in the studio to reconsider—but now clownish as much as menacing. Simultaneously he took to making single-image acrylic panel paintings of these same iconic abbreviations, and then small oils that he hung in tiers around the bedroom adjacent to his large studio next to his Woodstock home, where he could consult them at will like a writer browsing a dictionary or thesaurus.

• Philip Guston: A Life Spent Painting, Robert Storr, Laurence King, 360pp, £60 (hb), published 14 September

• See The Art Newspaper’s September issue for a review of the book