As global warming becomes dire and natural resources increasingly depleted, the designer and architect Neri Oxman wants to make work that not only makes us more aware of these problems, but also offers possible solutions. Her exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), Nature x Humanity: Oxman Architects (until 15 May), explores issues of sustainability through futuristic design and models, and objects made from organic matter.

One pairing especially notable for its size and experimental nature is Aguahoja I and its newer iteration Aguahoja III, presented in two different locations; the first outside on a museum terrace, the second indoors at the entrance to the exhibition. They call our attention to preservation and decay, suggesting a way to a more ecological balance. They also call on a different set of skills and diligence from the museum’s chief conservator, Michelle Barger.

Each piece is five meters tall and resembles a cocoon standing on end, although the name “aguahoja” means “water leaf” in Spanish. They are made of bio-composite panels inserted into a polymeric scaffold and were 3-D printed at labs at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where Oxman taught in the Media Arts and Sciences Department. During a Zoom interview, Barger holds up a sample panel—it’s thick, brown and fibrous, like coconut shell, with the outer layer made up of cellulose from leaves and chitosan from shrimp shells and the backing layer made of pectin from apples. While Aguahola III is meant to stay relatively pristine, Aguahola I is expected to unravel and decompose.

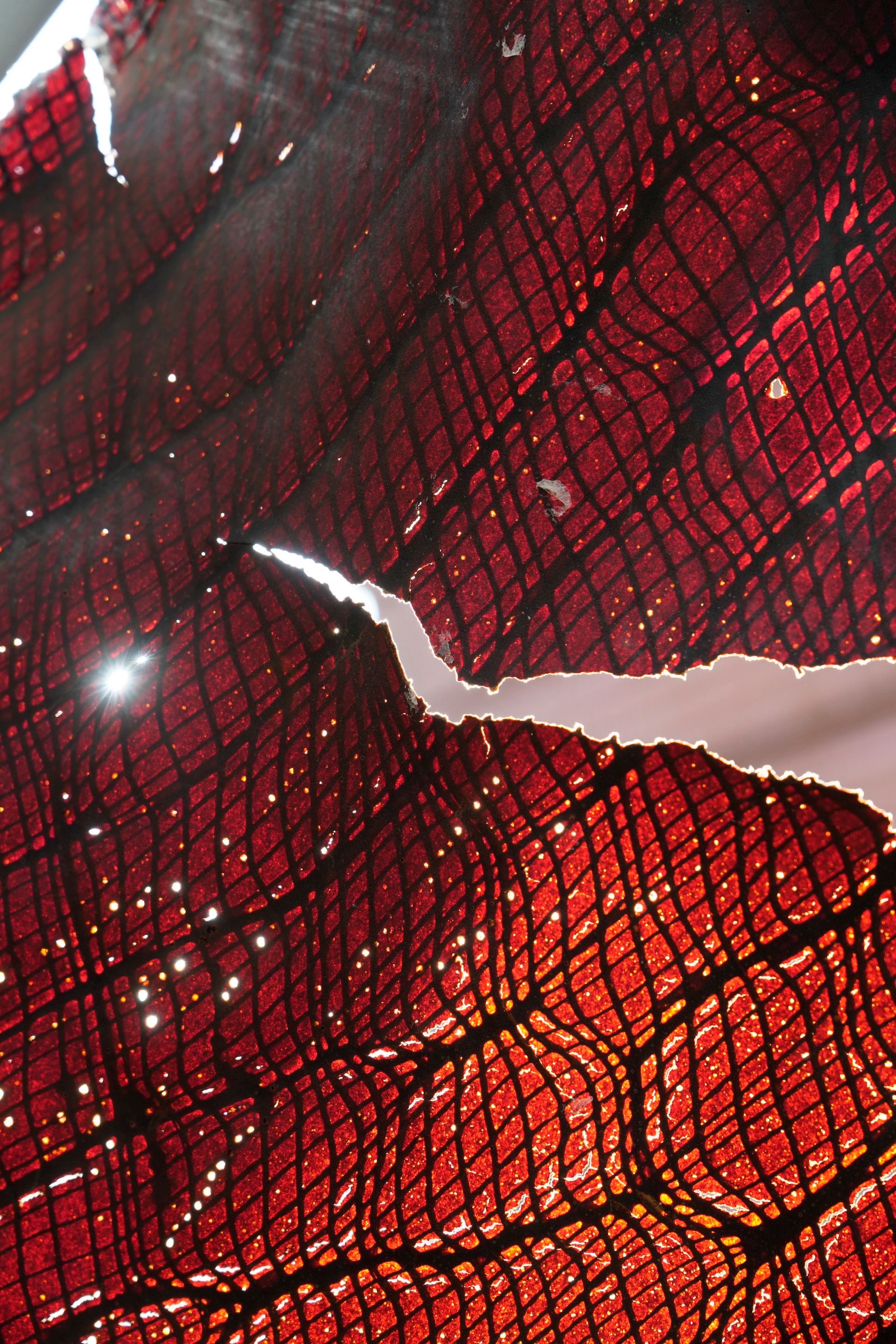

Detail of Neri Oxman's work showing signs of decay at SFMOMA Courtesy SFMOMA

A work made with such unconventional materials presents several challenges. “We have two states that the work is in,” says Barger. "One, what does it mean to own this piece and preserve it as something in our collection? And then, how do we hope to present it during an exhibition?"

A month into the exhibition, the outdoor sculpture has already been effected by San Francisco’s moody weather. The panels are now drying, curling and popping out of their frame. When they do pop out, they fall into a large planter filled with dirt—thus, says Oxman, returning “the energy stored in their materials to other organisms”. When panels on the sculpture inside pop out, Barger reinserts them into their grooves, sometimes using a steamer to soften the material. “The pectin layer is already dissolving,” she says, but she’s letting that process take place.

Oxman calls her approach to sustainability “material ecology”. “While sustainability aims to avoid the depletion of natural resources to maintain an ecological balance,” she says, “material ecology aims to augment natural resources—not to maintain but to advance, recover, replenish and even regrow and renew ecological niches. To achieve this, we need to design with, and construct structures made entirely, or by large part, from bio-based materials, or biopolymers.”

Installation view of Oxman Architects: Nature x Humanity at SFMOMA Photo © Matthew Millman Photography

Visitors will naturally compare the two, and Barger says there are vantage points from which you can see both. Aguahola I is accompanied by measuring instruments, including weather gauges and a caloric clock that calculates the number of calories remaining in the structure—both for visitors to look at and for the artist and museum staff to study.

Questions remain as to how much staff should intervene, if at all, and Barger says a meeting is planned this month to discuss those issues. “There’s nothing like an exhibition to get all the right people together,” she says. “Also, with contemporary art, we have the benefit of the artist being alive and get to ask her questions.”

- Nature x Humanity: Oxman Architects, until 15 May, at SFMOMA.