The 2022 Whitney Biennial, Quiet as It’s Kept, can be disorienting—an effect that is often intentional. Co-curators David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards, both curators at the Whitney Museum, have cited the collapsed sense of time and compounding political, health and humanitarian crises of the past three years (they began work on this biennial, which was originally due to open last year, in the comparatively calm year of 2019) as influences not only on their selection of 63 artists and collectives, but also on the way their works are installed.

More than any biennial in the Whitney’s new building (this is the third), Quiet as It’s Kept has fundamentally remade the galleries’ architecture, and generally to great success. The bulk of the biennial is installed on the museum’s fifth and sixth floors, and the two could not be more distinct. The lower level is an expansive white, light-filled hall without a single dividing wall, only suspended and freestanding partitions. This makes for airy, expansive views and variable pairings of works as visitors move through the space (and, in a few instances, some very confusing wall label placement). The sixth floor, by contrast, is almost entirely dark, consisting of a series of dimly lit alcoves and antechambers with black walls and carpeting.

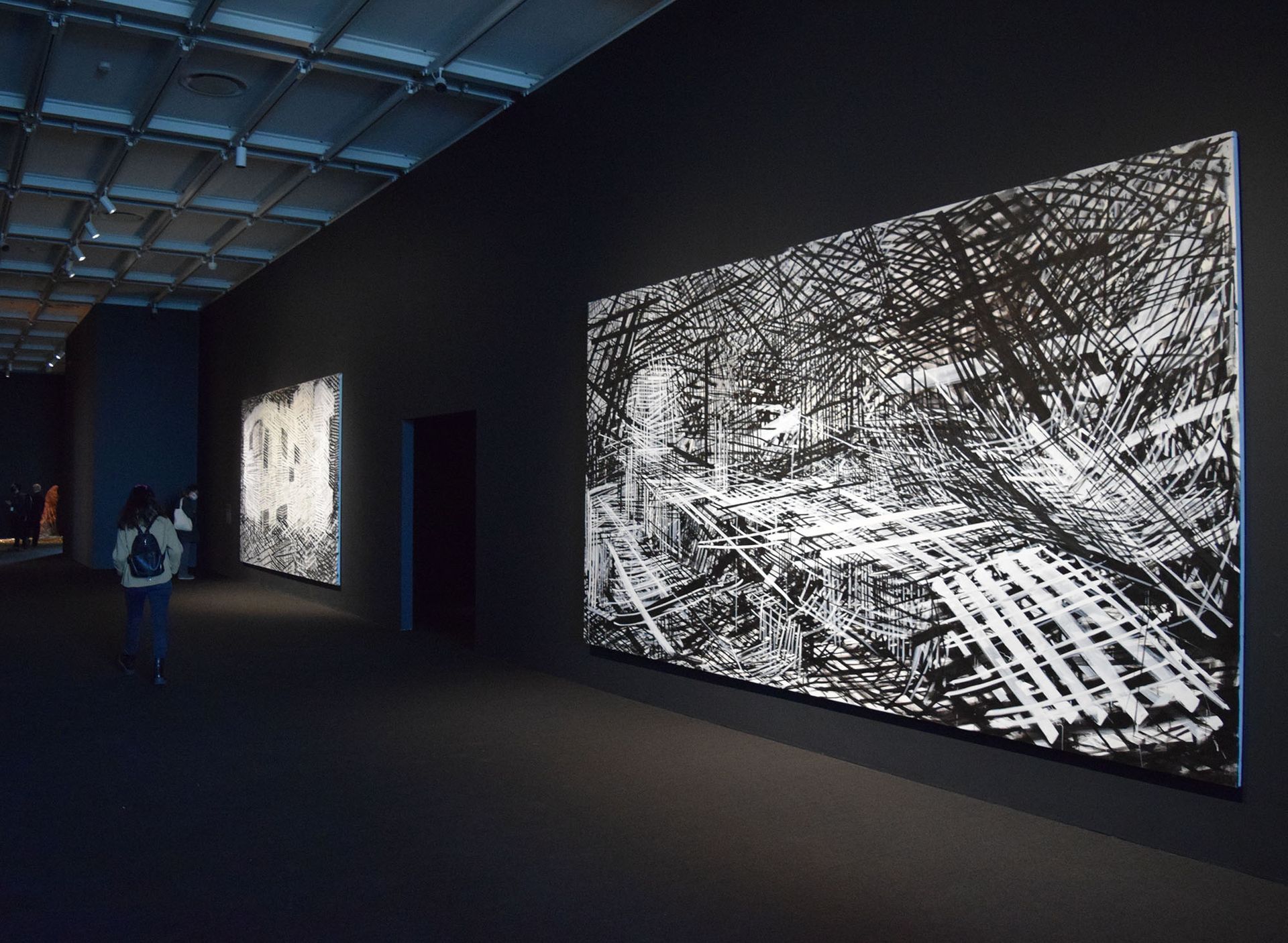

Works by Denyse Thomasos on the sixth floor of the Whitney Museum Photo © Benjamin Sutton

If the dominant features of the installation on the fifth floor are light and expansiveness, the sixth floor creates a palpable sense of constriction and claustrophobia. Broadly speaking, this architectural dualism matches the tenor of the works on each floor. Colourful, playful and meditative works are primarily found on the fifth floor, while the sixth houses many of the exhibition’s grimmest and headiest works. But this duality of lightness and brightness versus heaviness and darkness is far from the only way to think about this biennial. Here, then, are five themes through which to explore Quiet as It’s Kept.

Alternative abstraction

The Whitney Biennial has long served as the most prominent temperature-check of American contemporary art. The 2022 edition (its 80th iteration) may give uninitiated visitors a very distorted sense of the field of contemporary painting, in particular. Whereas most commercial galleries and auction houses are singularly focused on selling figurative paintings these days, they are almost absent from the biennial (and most examples included are underwhelming). Instead, the exhibition is awash in powerful abstraction, much of it made using unconventional materials and methods.

Rodney McMillian, shaft, 2021-22 Photo © Benjamin Sutton

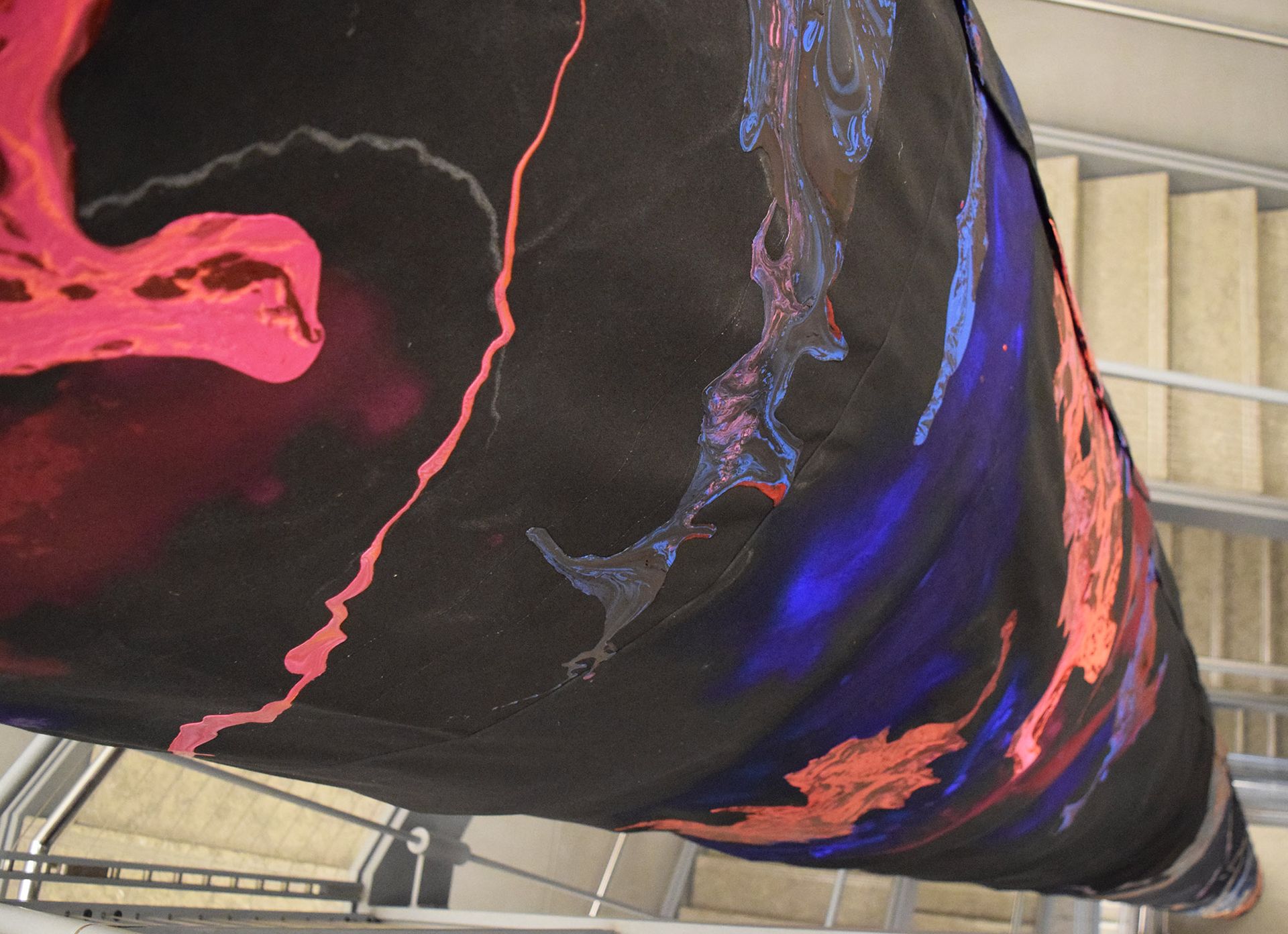

Visitors taking the stairs, for instance, will circle an imposing Rodney McMillian painting, shaft (2021-22), which resembles a stack of paint-splashed oil drums. The artist has described the six-storey-tall composition, made with acrylic, latex and vinyl paint, ink and paper on canvas, as a portal and “an object that incorporates painting”. The same could be said of Omaskêko Ininiwak artist Duane Linklater’s works on display on the fifth floor, which are based on teepee covers. He leaves circular canvas and linen supports outside, employing the elements and organic materials to transform them. His large, loosely hanging paintings are resolutely abstract, yet they record natural processes. Some also feature syllabic characters from the Cree language, Ininîmowin.

Nearby, Lisa Alvarado’s brilliant trio of Vibratory Cartography paintings (2021-22), hung from the ceiling like banners to reveal their patterned burlap backs, similarly result from a unique style of application. They are shaped by the painter and harmonium player’s musical performances and reflect the ways in which colour and sound influence the body’s movements. A couple of freestanding partitions away, Sičangu Lakota artist Dyani White Hawk’s dazzling glass bead composition Wopila | Lineage (2021) builds on the traditional motifs and methods of Lakota beadwork, which typically involves embroidery done with porcupine quills. It also references works by canonical white male practitioners of abstract painting whom the Whitney has long championed in its narrative of American Modernism, like Barnett Newman and Frank Stella.

Works from Lisa Alvarado's Vibratory Cartography series (2021-22) Photo © Benjamin Sutton

There are plenty more inventive approaches to abstraction in the biennial, from James Little’s superb geometric canvases to Aria Dean’s irreverent greenscreen-hued monolith—digitally generated and fabricated to look something like a John McCracken sculpture that got into a car accident—and performance artist EJ Hill’s truly minimalist contribution: a page in the exhibition catalogue printed a specific shade of light pink.

Systems of exclusion and control

If there is one large-scale work in this year’s biennial that is impossible to ignore in its magnetism, it is Sable Elyse Smith’s kinetic ferris wheel sculpture A Clockwork (2021). The towering construction is made from a type of aluminium table and seat used to furnish visiting rooms in prison, and its slow but continuous movement offers a grim commentary on the grinding machinery of America’s bloated and exploitative correctional system—or, as the artist puts it, “a physical monument to our entanglement of violence and entertainment”.

Sable Elyse Smith, A Clockwork, 2021 Photo © Benjamin Sutton

At the same end of the Whitney’s fifth floor, Emily Barker’s comparatively understated installation considers systemic violence of a different sort. Behind a stack of 7,865 sheets of paper—copies of medical bills and plans for the artist’s care between 2012-15—stands Kitchen (2019), an installation that consists of generic kitchen cabinetry rendered in clear plastic and with a countertop as tall as the average American man. The installation evokes the artist’s experiences of navigating the world in a wheelchair and the myriad ways in which we fail to address the needs of people with disabilities.

Access of a different sort is the focus of Beirut-born artist Rayyane Tabet’s 100 Civics Questions (2022), a text installation throughout the museum’s interior, exterior and website. It consists of questions from the US naturalisation test, which applicants for US citizenship (like Tabet) must take. They range from straightforward questions—like ”When do we celebrate Independence Day?”, tucked into a stairwell alcove—that nonetheless imply charged assumptions about who is included in “we”, to the more ominous, like “What is the rule of law?” on the exterior of the Whitney’s restaurant.

Rayyane Tabet, 100 Civics Questions, 2022 Photo © Benjamin Sutton

Another artist examining the boundaries of American belonging, albeit in a more landscape-based manner, is Alejandro “Luperca” Morales. His Juárez Archive (2020-present) consists of 36 magnifying keychains each containing a slide of a different image of his hometown of Ciudad Juárez, a city on the Mexico-US border with Texas. Unable to travel home because of the pandemic, Morales was left to experience Juárez virtually, and these tiny, glitchy streetscapes sourced from Google Maps attest to the ways the city has been reshaped by conflict, from drug wars to its increasingly militarised border.

The militarisation of the police is the starting point for what seems destined to be one of this biennial’s most talked-about works, by one of its best-known participants, the Chilean conceptual artist Alfredo Jaar. His video installation 06.01.2020 18.39 (2022) consists of video footage of a Black Lives Matter protest on the titular date in Washington, DC, when, infamously, federal forces used flash grenades and other tactics to disperse peaceful protesters from in front of the White House before Donald Trump staged a photo outside a nearby church. Later, National Guard helicopters flew very low over protestors to further intimidate them.

For Jaar, the incident is “when I realised that I was witnessing fascism. Fascism had arrived in the USA”. The video is installed in an enclosed room that a limited number of viewers can only enter between showings. The ceiling is outfitted with an array of powerful fans that accelerate as the video goes on, mimicking the aggressive wind generated by the helicopter blades. For all the work’s severity and theatrics, it feels oddly flat and underdeveloped. Like so much earnest art made in immediate response to protests or footage of social justice movements, it struggles to transcend the material or say anything new about it.

Sleight of hand

Partial view of Daniel Joseph Martinez, Three Critiques* #3 The Post-Human Manifesto for the Future; On the Origin of Species or E=hνÓ (+) We are here to hold humans accountable for crimes agains humanity OR In the twilight of the empire, in the spider hole where the masters of the earth have gone to ground with their simulacral weapons, reality gives way to a violent Technological Phantasmagoria Celestial Event or Homo Sapiens are the Ultimate Invasive Species on the Earth or MODERNISM has failed us, the EMPIRE is collapsing, humans are MORALLY indefensible or A world between what we know and what we fear or Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is an absurd one Or Homines corruptissimi Condememant quod non intellegunt Photo © Benjamin Sutton

Jaar is far from the only artist incorporating illusion and simulation in his biennial work. Just around the corner is a startling five-photo piece by Daniel Joseph Martinez in which the artist appears elaborately costumed and made up to resemble five famous sci-fi characters including Frankenstein’s monster, Dracula and a Drone Host from the series Westworld. The images reflect the artist’s interest in the many ways we can transform and remake ourselves to be, in some sense, “post-human”.

Down on the fifth floor, an eight-channel video and sculpture by Mexican artist Andrew Roberts also borrow from science-fiction but imagine a thoroughly branded post-human world. In his video La horda (The horde) (2020), computer-animated zombie workers sporting corporate outfits from Uber Eats, Google, Walmart and other companies recite poetry, reflecting their apparently nascent sense of class consciousness. On a nearby plinth, a very realistic sculpture of a dismembered forearm is tattooed with Amazon’s ubiquitous smiling logo, an especially prophetic piece considering that workers at one of the multinational’s New York City warehouses have just voted to form the company’s first union.

Andrew Roberts, CARGO: A certain doom, 2020 Photo © Benjamin Sutton

On an adjacent wall, a series of seemingly candid large-format photographs by Buck Ellison are actually a very different exercise in corporate visioning. The photos capture Ellison’s elaborately staged approximations of moments in the private life of Erik Prince, the founder of the para-military firm Blackwater, in 2003, the same year the company was awarded its first contracts to participate in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Given that context, the seemingly innocuous images of a young outdoorsman take on a very dark edge.

Conceptual and performance artist Nayland Blake’s contribution is a far more celebratory type of illusion, a homage to a historical local institution. At the rear of the Whitney’s glass-walled lobby, they have transformed a doorway into a replica of the entrance to the Mineshaft, a legendary members-only leather bar that was located just a block away until its closure in 1985.

The chameleonic artist Alex Da Corte’s hour-long video ROY G BIV (2022), one of the biennial’s precious few comical works, also involves some very complex illusions (and allusions). It features the artist in elaborate costumes and makeup as Marcel Duchamp, as Duchamp dressed as his female alter ego Rose Sélavy, then as Duchamp dressed outrageously as the Joker from the 1989 Batman film. Finally, Da Corte is seen as a singing Brancusi sculpture. It is projected onto a large cube that will be repainted in various colours over the course of the biennial by the artist’s brother, a professional housepainter, in hommage to John Baldessari’s wry 1977 video Six Colourful Inside Jobs.

The collecting impulse

Alex Da Corte, ROY G BIV, 2022 Photo © Benjamin Sutton

Da Corte’s piece is emblematic of another thread running through the 2022 biennial, which is a fascination with collections. The entire video is set in a re-creation of the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s gallery displaying its collection of Brancusi sculptures. In the video, Da Corte as Duchamp as the Joker gleefully uses a giant neon paintbrush to give these austere Modernist masterpieces—works like Bird in Space and Mademoiselle Pogany—bright, chromatic makeovers. In doing so, he figuratively and then actually brings this historic collection to life.

Near the other end of the fifth floor is one of several installations in this year’s biennial that function as miniature exhibitions-within-the-exhibition, a semi-enclosed show of works by the late Korean-American artist and author Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. The presentation makes clear that a bigger show of Cha’s sharp and understatedly irreverent conceptual work is in order.

Just beyond, the New York artist Rose Salane is exhibiting a fascinating collection, bought at a Metropolitan Transit Authority auction, of so-called 'slugs' — modified or fabricated coins used to replicate the proportions of legal tender in order to avoid paying full bus fare. For the biennial, she exhaustively sorted them into five sub-collections, each displayed on its own plinth with a framed catalogue on the nearby wall. “The thousands of slugs are artefacts of the moment an individual entered the transit system and symbolise the way one might need to outwit such a system just to get by,” Salane writes in her catalogue entry.

Nearby, a triptych of mixed media panels by Renée Green, Lesson (1989), features images of objects from museum collections framed by two contrasting quotes, one from Jules Verne and the other from a Paul Valery poem, both of which muse on museums’ ability to function as custodians of artefacts. Where Valery’s text holds deep reverence for the functions museums serve, Verne’s implies a distrust of institutions (an apt dualism in an exhibition that, in recent years, has sparked controversy more often than not). Green’s own poetry is also featured in the biennial in the form of Space Poem #7 (2020), a group of bright textile banners installed in the museum’s lobby.

The journey

Right off the lobby, in the museum’s ground-floor gallery, a gorgeous 36-minute video by the collective Moved by the Motion (founded by artists Tosh Basco and Wu Tsang in 2013) is projected on a curved screen with a wooden, sloping floor. The staging mimics the nautical setting of the video, EXTRACTS (2022), which features additional scenes and rearranged segments from the group’s feature-length piece MOBY DICK; or, The Whale (2022), screening later this month 20 blocks north at The Shed. Melding elements of Herman Melville’s source material with Afrofuturist imagery and contemporary dance, it is a haunting, transformative re-imagining of a familiar text.

Moved by the Motion (founded in 2013 by Tosh Basco and Wu Tsang), EXTRACTS, 2022 Photo © Benjamin Sutton

Back up on the sixth floor, another nautical journey poetically responds to the unfamiliar world we have all inhabited for the past two years. In Your Eyes Will Be an Empty World (2021), Cuban-American artist Coco Fusco rows a boat around Hart Island, site of New York City’s potter's field, where in 2020 unclaimed Covid-19 victims were buried in mass graves. Fusco’s act of remembrance and mourning for the pandemic’s forgotten dead places the still-unfolding crisis alongside earlier epidemics, many of whose victims were also interred on Hart Island.

In drone footage of the tiny spit of land where so many New Yorkers are buried, Fusco’s video approximates an experience Edwards cites in her catalogue essay, known as the “overview effect”, which was described by astronauts upon seeing the Earth from space and understanding the planet in a new light, having become keenly aware of its smallness and fragility. The most powerful works in Quiet as It’s Kept offer some version of that reoriented awareness, a heightened sense of how much the world has changed since the last biennial, becoming both more fragile and more vivid—simultaneously darker and brighter.

- Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept, until 5 September, Whitney Museum of American Art.