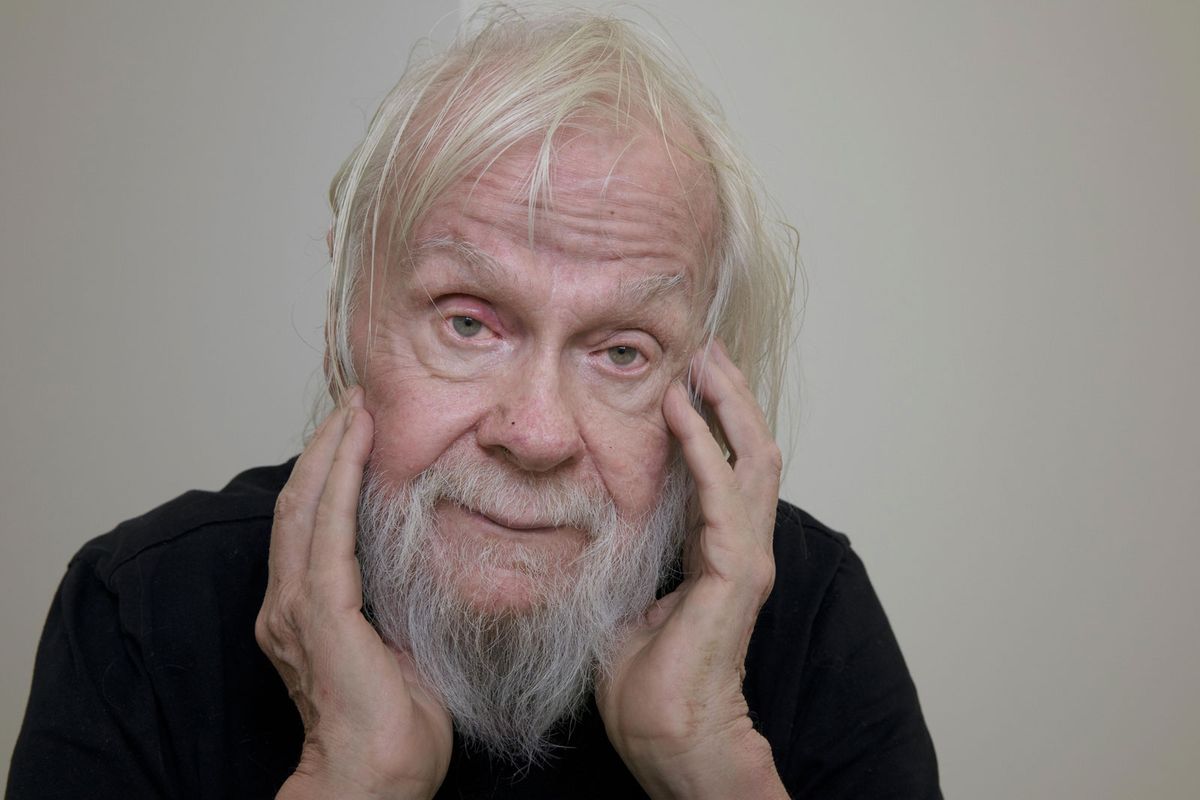

John Baldessari, the Californian artist and teacher known as the godfather of conceptual art, has died aged 88.

His death on Thursday at his Los Angeles home was confirmed last night by his long-time dealer Marian Goodman who described him as “intelligent, loving and incomparable”.

At 6 ft 7 inches tall, Baldessari was a towering presence in more ways than one. Over the past five decades, he had more than 200 solo shows and 1,000 group shows and won numerous awards including the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement at the Venice Biennale in 2009 and the National Medal of Arts from President Barack Obama in 2014.

A thinker and, in his own words, “a frustrated writer” (there was a short-lived stint as a critic in the 1950s), Baldessari constantly probed and pushed the parameters of art. He gave words and images equal weight and rejected the hand of the artist, choosing instead to employ professional sign painters to create his text works.

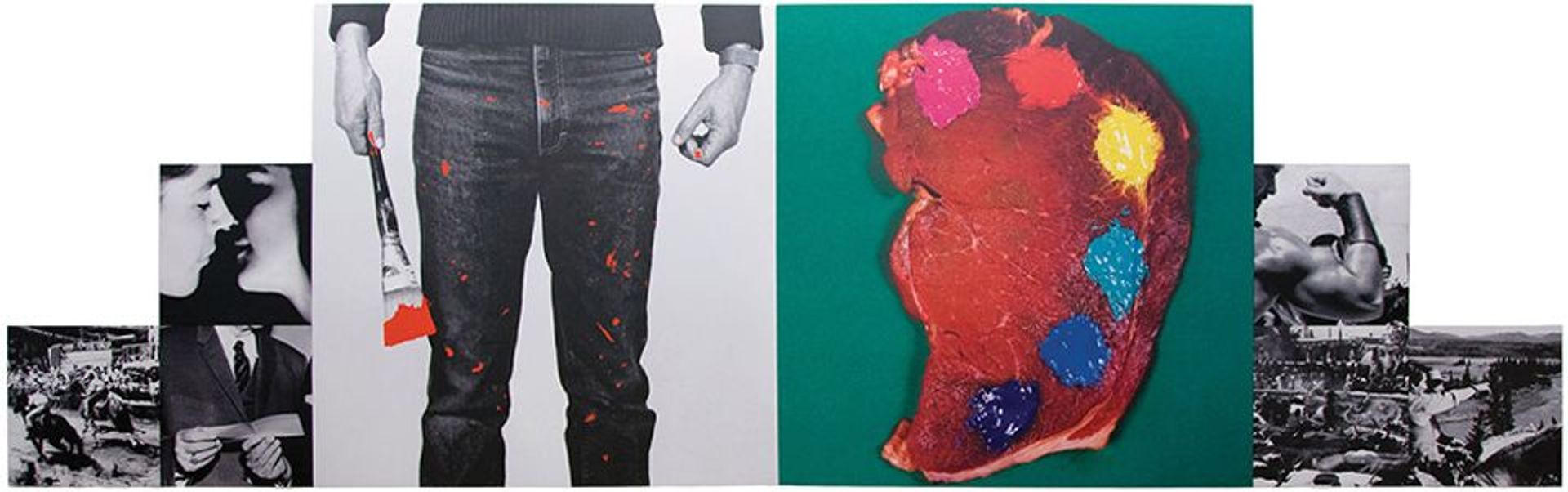

John Baldessari’s Stake: Art is Food for Thought and Food Costs Money (1985) in the Rubell Museum © John Baldessari

Counter to the puritanical seriousness of conceptual art, his approach was often irreverently humorous, although he once said the word funny made him “feel uncomfortable”. In a 2013 interview he told his friend and former student the artist David Salle: “I don’t try to be funny. It’s just that I feel that the world is a little bit absurd and off-kilter, and I’m sort of reporting.”

His decision to ditch gestural painting for language and ideas came early on, while teaching in the San Diego area in the early 1960s and painting in his spare time. “I decided, in some Cartesian way, that I was going to figure out what art meant to me. What was the bottom line,” he told the Los Angeles-based critic Christopher Knight in 2012.

“I finally decided that anything on canvas […] was the signal for art. You could do anything you wanted on it. And it was art.”

“I don’t try to be funny. It’s just that I feel that the world is a little bit absurd and off-kilter, and I’m sort of reporting.”John Baldessari

This lighting bolt gave rise to his text and photo-text paintings created between 1966 and 1968—hybrid compositions of photography, text and painted images. The best-known example features an amateur-looking snapshot of Baldessari posing in front of a palm tree, which looks as if it is growing out of his head. Underneath is printed the word “wrong” in capital letters. “There's no such thing as a bad photograph,” he famously said. Just poorly composed ones, perhaps?

A turning point came in 1970. It was the year Baldessari was appointed to teach at the California Institute of the Arts (he taught there until 1986 when the booming market allowed him to live off art sales for the first time). Paul Brock, then the dean of the university, visited Baldessari in his studio. Baldessari recalled: “He said: ‘I get it, you import your culture.’ And it was true, I learned everything from books and magazines.”

This was also the year that Baldessari burned all of the paintings he made between 1953 and 1966. He titled the work Cremation Project, transferring the ashes to a bronze urn in the shape of a book. An accompanying bronze plaque was inscribed with the words “John Anthony Baldessari—May 1953-March 1966”, as much a memorial to his own corporeality as the cremated body of work.

The art market and its penchant for brand names was a rich source of parody. In Tips For Artists Who Want To Sell (1966-1968), Baldessari suggests: “Generally speaking, painting with light colours sell more quickly than paintings with dark colours”. Another so-called “tip” hints at the sexism underlying the market: “Subject matter is important: it has been said that paintings with cows and hens in them collect dust… while the same paintings with bulls and roosters sell.”

In a recent body of work exhibited at the Garage Museum in Moscow in 2013, Baldessari turned Andy Warhol soup cans blue and green and attributed them to Sol LeWitt, while Jackson Pollock’s painterly abstractions were recast as by the hand of Henri Matisse. Hans Ulrich Obrist, the show’s curator and artistic director at London's Serpentine Galleries, described Baldessari as a “serial inventor”.

Baldessari’s own market really took off in the late 1990s when he made the hard decision to move from Sonnabend Gallery (where he had shown for 26 years) to Marian Goodman. The Miami collector Craig Robins was an early supporter, buying his first work by Baldessari in around 1990. Robins recalls: “After acquiring works by many of the young Los Angeles artists, I realised that most were very influenced by John and thought that he would anchor the collection. Then I built a comprehensive group of John’s work from the 1960s to the present at which point I realised that I had no choice but to acquire a Duchamp.”

Through his teaching, both at CalArts and at the University of California, Los Angeles, from 1996 to 2005, Baldessari is credited with cultivating the city’s contemporary art scene. Many of his students including Mike Kelley, Tony Oursler, Jim Shaw, Matt Mullican, Jack Goldstein, Liz Larner, Mungo Thomson and Analia Saban have gone on to become major players.

Their tributes affirm the extent of Baldessari's influence. David Salle tells The Art Newspaper: “John succeeded in making a big-time style out of neglected or un-promising materials. He presented abstract, philosophical concerns cloaked in wit and humor. Later on, he added visual glamor. It was a winning combination. His influence is very wide. John was enormously generous and kind, and I will miss him terribly.”

Saban says: “He supported every student individually and validated their ideas even when they didn’t fit traditional definitions of art.”

Oursler describes Baldessari on Instagram as “a fountain of creativity, always with a smile and obscure joke”. He adds: “He once curated a show titled God and there were more than a few jokes about bearded men in the sky.” Thomson says: “I feel like my art dad died today, and I imagine a lot of people feel the same. John has an army, which is why I once made antenna balls of his face (to his great chagrin)—so his army could have a banner.”

In a short film made in 2012, Baldessari said he will be best known in 100 years for putting dots over people’s faces. His legions of friends and admirers say he will be remembered for far more than that.