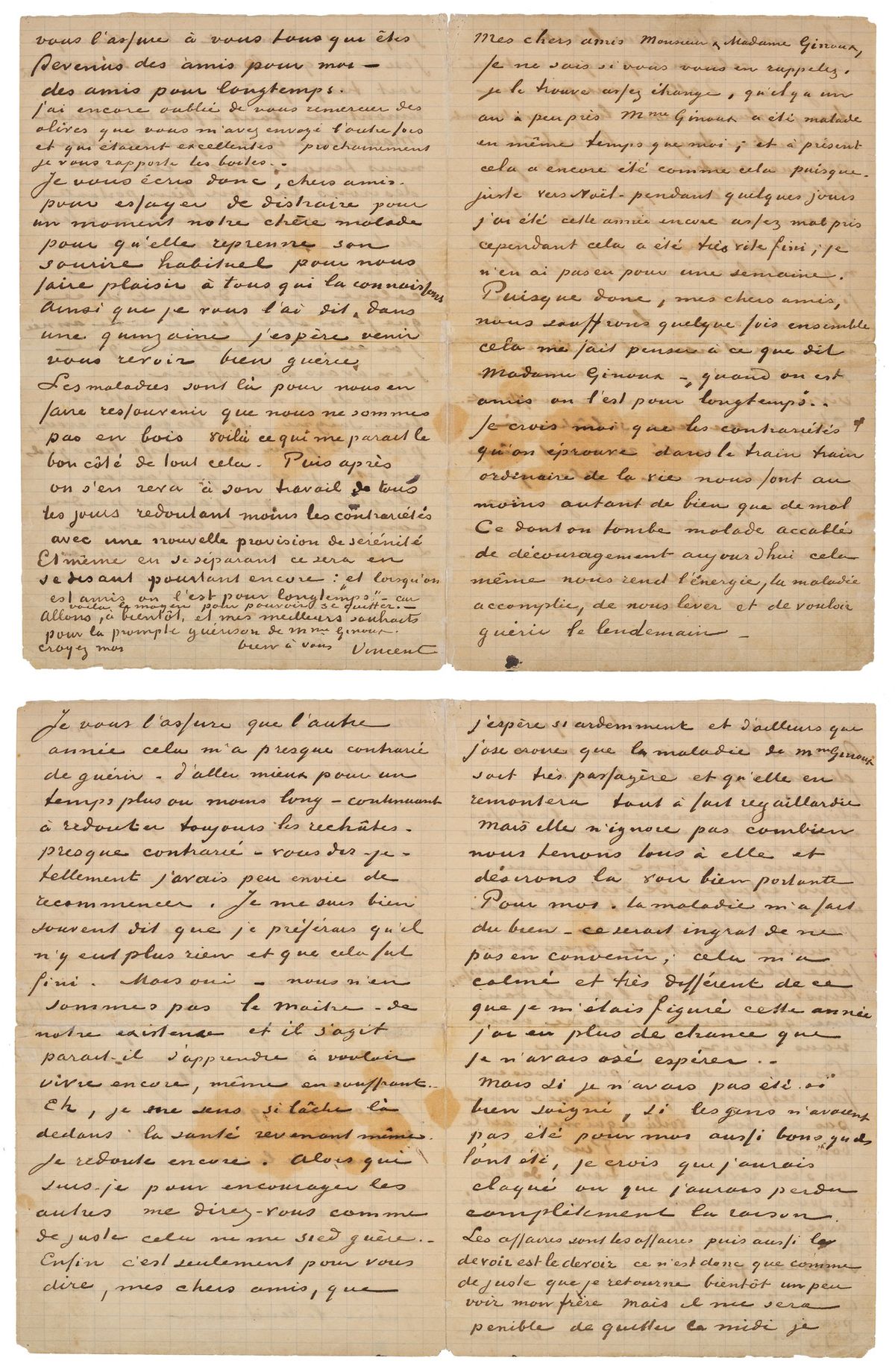

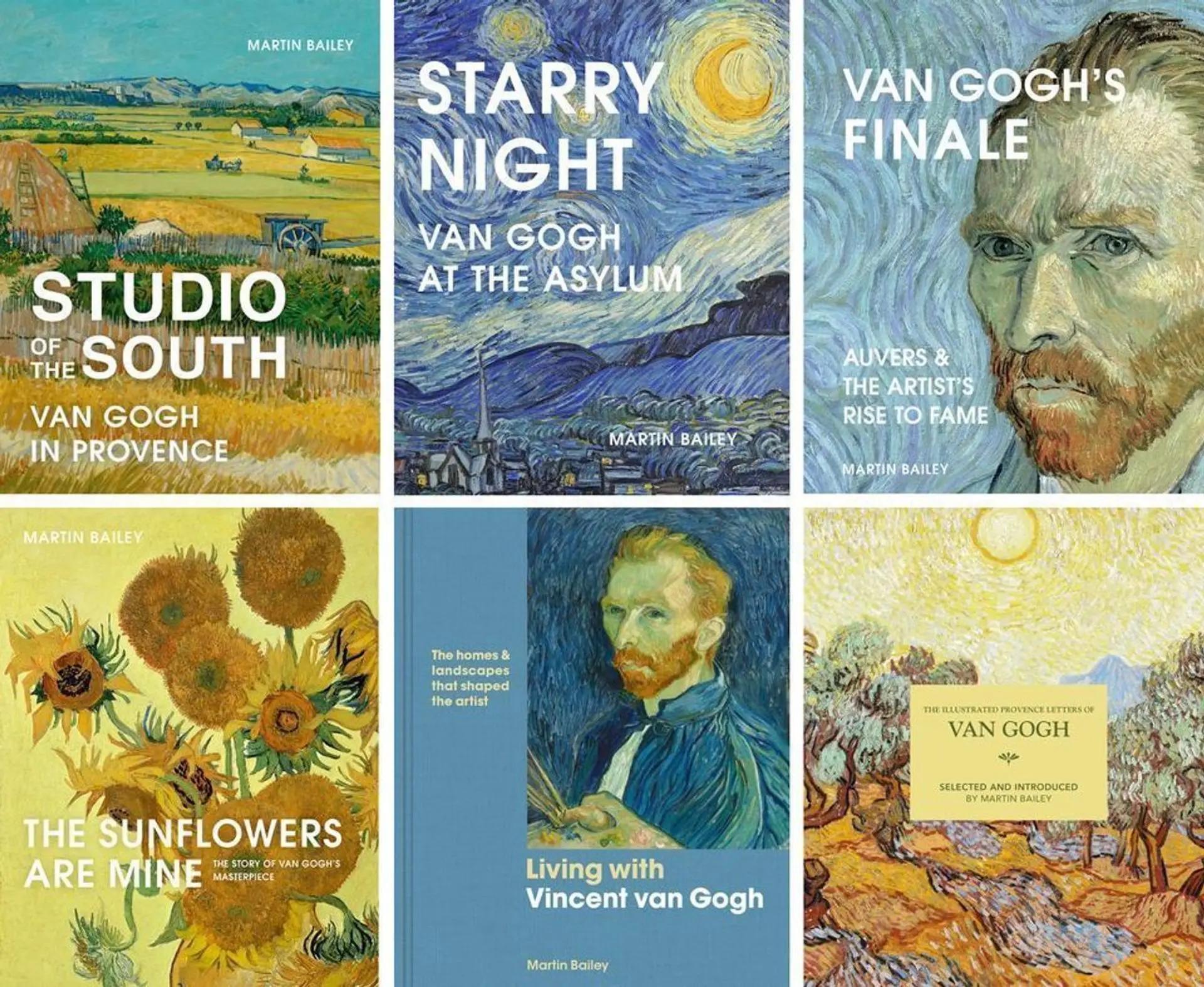

Van Gogh’s letter to the proprietors of the Café de la Gare in Arles will come up for sale next week. This single sheet of paper, slightly smaller than A4, is estimated to fetch €200,000-€250,000 at the Aguttes auction house on the outskirts of Paris.

Van Gogh's letters are among the most valuable of any artist. The 5 April Aguttes sale also includes letters estimated at €1,000 or less by Degas, Manet, Matisse, Monet, Renoir, Rodin, Signac, Sisley and Toulouse-Lautrec. A 1563 letter from the Italian Renaissance artist and pioneer art historian Giorgio Vasari has an upper estimate of €15,000. Although Van Gogh could not sell his art, his correspondence is now in a class of its own.

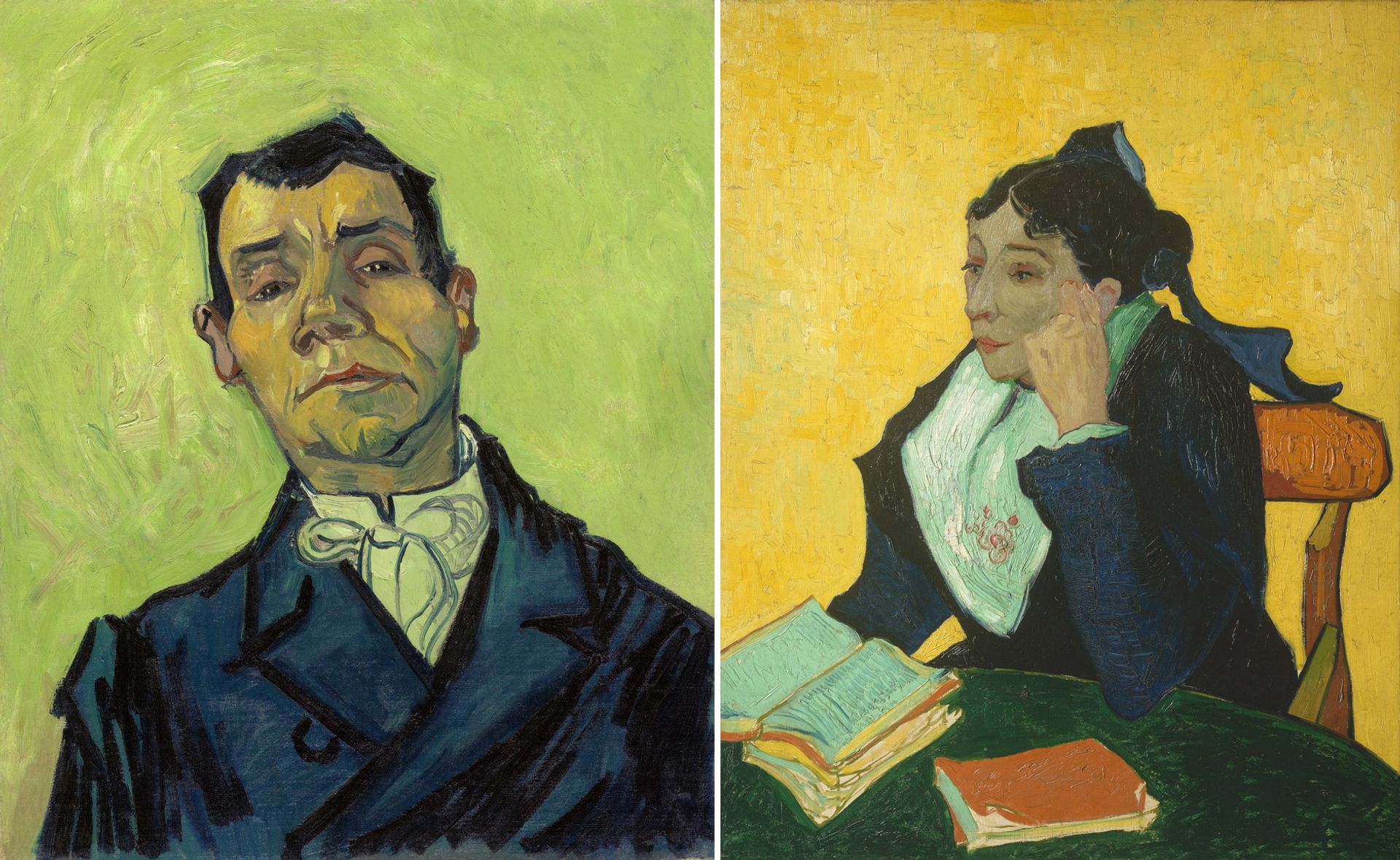

Van Gogh’s Portrait of Joseph Ginoux (1835-1902) (probably November 1888) and L’Arlésienne, Portrait of Marie Ginoux (1848-1911) (November 1888) Credit: Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo and Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Café de la Gare, which was run by the Ginoux couple, was, as its name suggests, just a few minutes from the railway station. As Vincent explained to his brother Theo: “It’s what they call a ‘night café’ here (they’re quite common here), that stay open all night. This way the ‘night prowlers’ can find a refuge when they don’t have the price of a lodging, or if they’re too drunk to be admitted.”

Vincent had rented a room above the café from May to September 1888, before he started to sleep at the Yellow House. Just before moving out of the café, he made a painting of the bar, with Joseph proprietorially standing by the billiard table.

Van Gogh’s The Night Café (September 1888) Credit: Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut

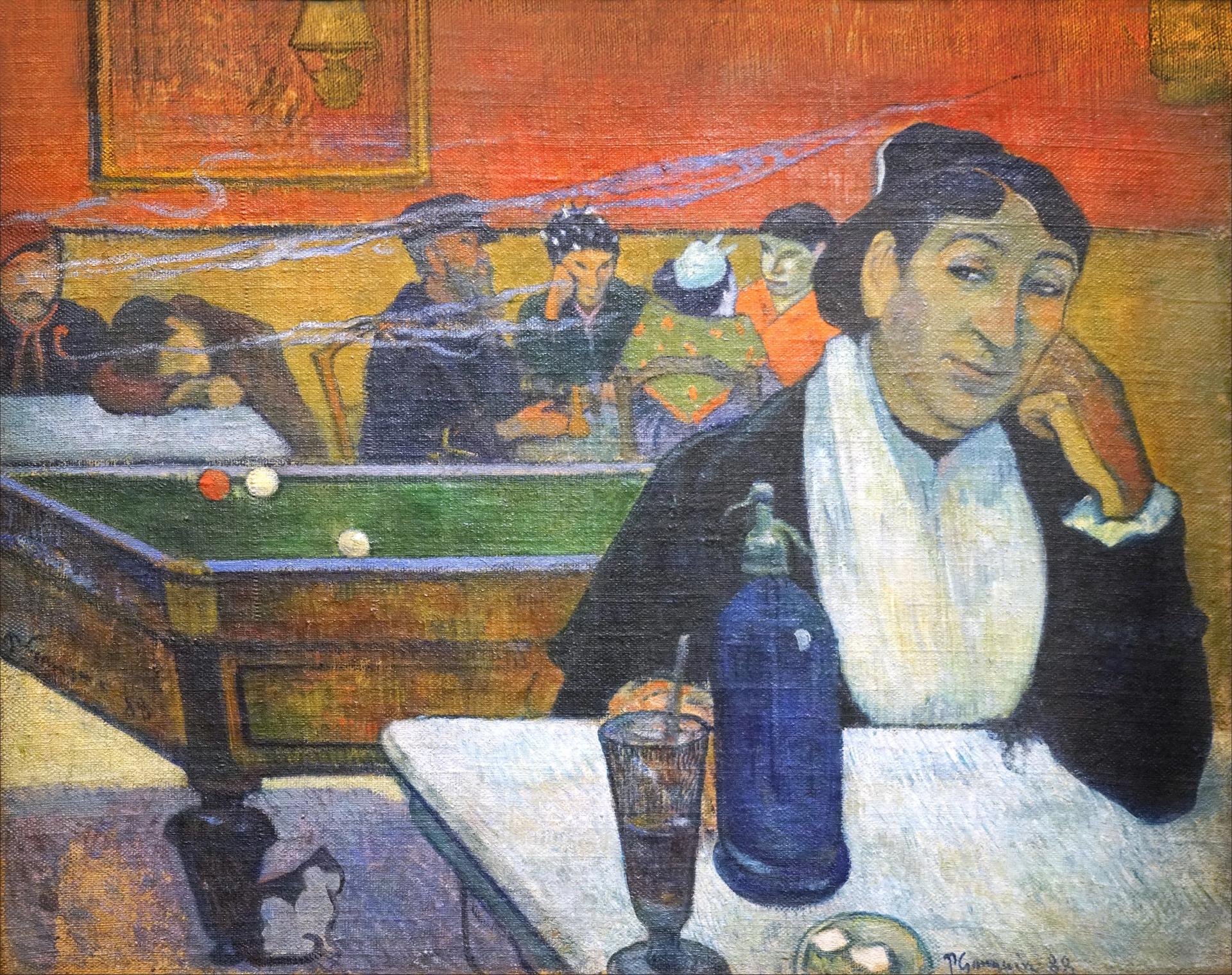

When Paul Gauguin arrived in Arles the following month, to stay with Van Gogh in the Yellow House, he made his own version of the scene—this time with Marie sitting by an absinthe and with a knowing look. Behind her are the billiard table, the café’s cat and half a dozen inebriated customers.

Paul Gauguin’s The Night Café (November 1888), Pushkin Museum of Fine Art, Moscow Photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra

The letter coming up for sale was sent to Marie and Joseph Ginoux from the asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, where Vincent had moved in May 1889. It was dated 20 January 1890, two days after he had paid a short visit to Arles to meet his old friends. He found that Marie had been unwell, seemingly suffering from the menopause.

In his letter, Vincent sympathised with Marie and then wrote about his own health problems, which he had faced since mutilating his ear a year earlier, just before Christmas 1888. This terrible incident had taken place in the Yellow House, just a few doors away from the café.

Five months after the mutilation Van Gogh had moved to the asylum, since he had found it too difficult to live independently. In late December 1889, while at the asylum, he suffered a further attack. This lasted just a few days and fortunately he did not harm himself.

In his letter, written three weeks after his recovery from this later attack, Van Gogh made the surprising observation that “the annoyances one experiences in the ordinary routine of life do us at least as much good as bad”.

He then went on to allude to suicidal thoughts he had when ill, although expressed slightly obliquely: “I’ve very often told myself that I’d prefer that there be nothing more and that it was over. Well yes—we’re not the master of that—of our existence, and it’s a matter, seemingly, of learning to want to live on, even when suffering. Ah, I feel so cowardly in that respect, even as my health returns.”

Although negative thoughts came and went, Van Gogh was determined to press on: “The thing that makes one fall ill, overcome by discouragement, today, that same thing gives us the energy, once the illness is over, to get up and want to recover the next day.”

Van Gogh ended his letter by assuring the Ginoux couple of his friendship—and thanking them for a box of olives that they had sent to the asylum. (Vincent loved olives and his sister-in-law Jo Bonger recalled that on a visit to Paris he had rushed out “to buy olives, which he used to eat every day”.)

A month after sending the letter Van Gogh painted no fewer than five versions of L’Arlesienne, a portrait of Marie made after a drawing by Gauguin (which Gauguin had used for his painting of The Night Café). This represented Vincent’s tribute to his friend Marie.

Van Gogh’s L’Arlesienne (February 1889), Kröller-Müller version Credit: Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

But Van Gogh’s remaining life would be tragically brief. Some of the thoughts expressed in his letter to the Ginoux couple eventually overwhelmed him. On 27 July 1890, Van Gogh shot himself in the abdomen, dying two days later.

And what happened to the letter coming up for sale? After Marie’s death in 1911 it was inherited by one of her nephews. In 1922, Van Gogh’s early biographer Gustave Coquiot visited the nephew, on a farm outside Arles, and was shown several of the artist’s letters. He described how “for 32 years they had slept in their tatty envelopes”.

In 1995 the letter of 20 January 1890 was auctioned in Paris, going to a US collector. It was sold on his behalf in 2012 by the Los Angeles auctioneer Profiles in History, going for an astonishing $290,000.

The buyer was Aristophil, a manuscript company run by Gérard Lhéritier. Aristophil was declared bankrupt in 2015, and its huge collection has gradually been auctioned off in the past few years—hence next Tuesday’s sale.

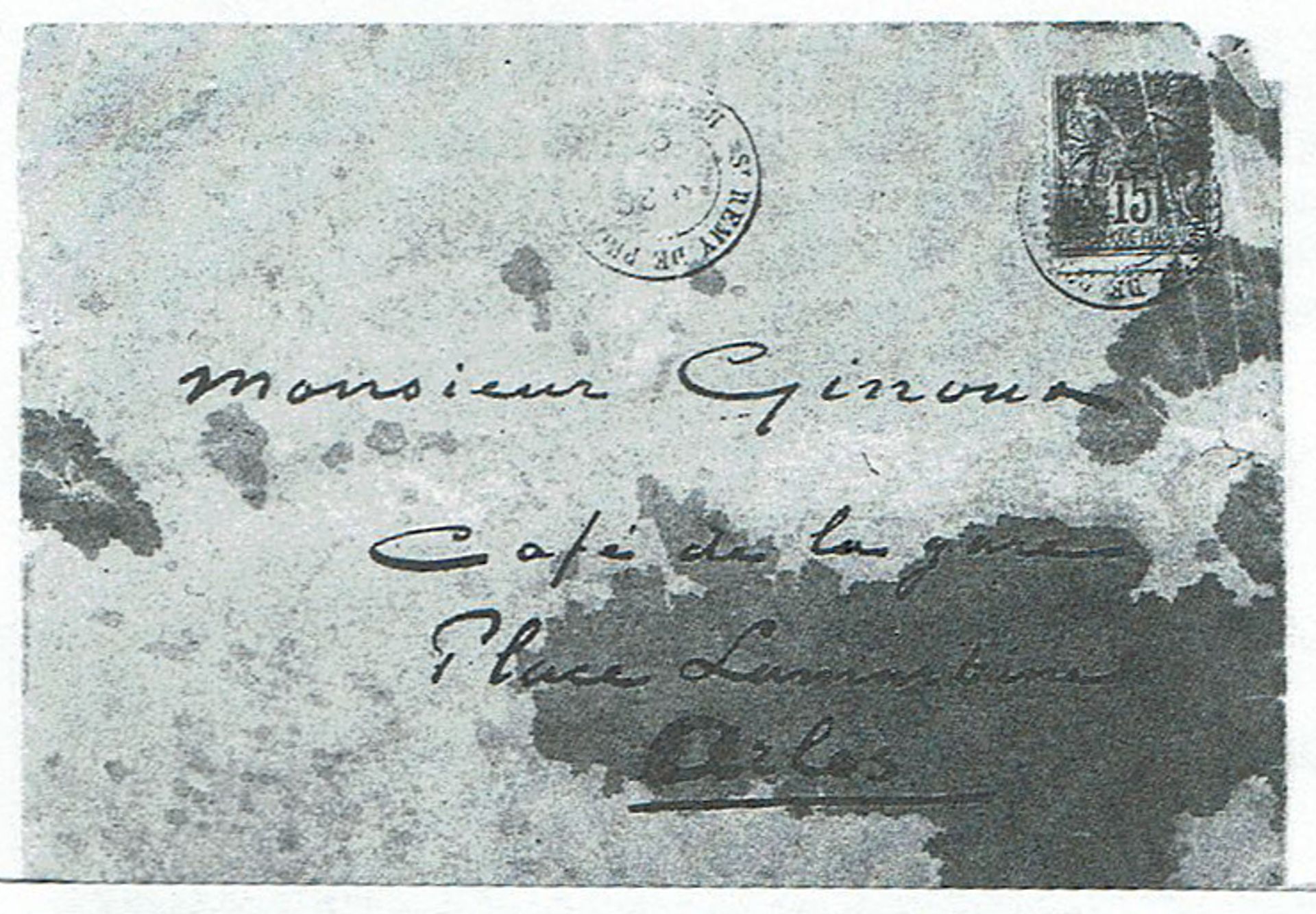

What was he fate of the tatty envelope that Van Gogh had addressed to Monsieur Ginoux? When the letter was auctioned in 2012 the envelope was included, but since then it has sadly gone missing.

Envelope (now lost) from Van Gogh’s letter to Marie and Joseph Ginoux, 20 January 1890

Photographs show that the lost envelope had a deep stain, which penetrated into the writing paper. We can only speculate, but just possibly it may have been caused by olive oil produced by the Ginoux family—from the olives so beloved by Van Gogh.

Other Van Gogh news:

• Aguttes is also selling several other Van Gogh items on 5 April: a small sketch, Head of a Man wearing a Hat (early 1887), estimated at €40,000-€60,000; a fragment of a Longfellow poem copied out in a now dismembered album (autumn 1876), estimated at €15,000-€20,000; and a letter of 2 September 1875 to a friend in The Hague, Egbert Borchers, estimated at €50,000-€60,000. The auction also includes 16 items by Van Gogh’s friend Paul Gauguin.