Six pages of poems and texts copied out by a young Vincent van Gogh for his Isleworth landlady have been treated as if they were the relics of a medieval saint: cut up and distributed to a number of owners. Scissors were used to dismember the manuscript, slicing it into pieces in an attempt to maximise its financial value.

This act of modern vandalism means that Van Gogh’s texts have been dispersed, with fragments scattered among unknown private collections. Since he wrote on both sides of three sheets, the poems on the reverse are cut off in the middle.

The Art Newspaper can reveal that half of Van Gogh’s texts have ended up at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, an innocent party in this scandal.

The pages were contained in a leather-bound album that originally belonged to Annie Slade-Jones, Van Gogh’s landlady in Isleworth, in west London. Her husband, the Reverend Thomas Slade-Jones, ran a school and Van Gogh, then aged 23, lived there while he worked as a teacher from October to December 1876, after he had been sacked as an assistant art dealer.

Annie Slade-Jones, Van Gogh's Isleworth landlady Photo: courtesy of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Vincent got on well with Annie, although she hated the smell of his ubiquitous pipe. On one occasion, he told his brother Theo, he gave her scented violets: “I bought some for Mrs Jones to make up for the pipe I smoke here now and then, mostly late in the evening in the playground. The tobacco here is rather strong.”

Annie had been given the album for her 16th birthday in 1855. For the rest of her life she invited close friends to write in this precious volume, with the last entry added just months before her death in 1923, aged 86. Altogether there are 180 pages of writing, from 60 friends.

Van Gogh’s 5,000-word contribution was among the longest. His texts came from published sources: poetry, passages from the Bible, hymns and literary writings. They were in Dutch, English, French or German—evidence of his linguistic skills. On a seventh page he pasted a print of Paul Delaroche’s Christ on the Mount of Olives (1855).

Another hand, probably that of Annie, wrote in pencil at the bottom of the last page of his text: “Vincent Van Hoch” [sic]. Without these pencilled words, Annie’s descendants would probably never have realised that the texts had been copied by her young Dutch lodger.

Detective work

The Art Newspaper has tracked down what happened to Annie’s album. It passed down to her granddaughter, Constance Violet Slade-Jones, who died in 1986. Late in life Constance gave the album to a relative, the playwright Francis Sewell Stokes.

Stokes tried to auction the album at Sotheby’s in London in 1977 and again the following year, but even with the Van Gogh pages it failed to sell. After his death in 1979, his heirs re-offered it at Sotheby’s in 1980. This time it sold—for just £550. John Wilson, an Oxford autograph dealer, bought it on behalf of a foreign dealer.

At some point later in the 1980s an unidentified person removed the Van Gogh pages from the album and cut out the individual texts. One double-sided leaf and four fragments, representing half the text, were later bought by Alistair McAlpine, a British Lord who assembled an eclectic collection of objects ranging from a Rothko painting to a dinosaur penis. In 1986 McAlpine sold much of his manuscript collection to the Getty, including the Van Gogh texts, via the American dealer Kenneth Rendell. These Van Gogh fragments were then valued at $9,000.

Getty curators knew that the texts had been written by Van Gogh, but did not realise that they had come from Annie’s album. The material was not illustrated online by the Getty until our inquiries and has only been consulted by seven people in the past 20 years. Curators at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam were unaware that the texts had ended up at the Getty.

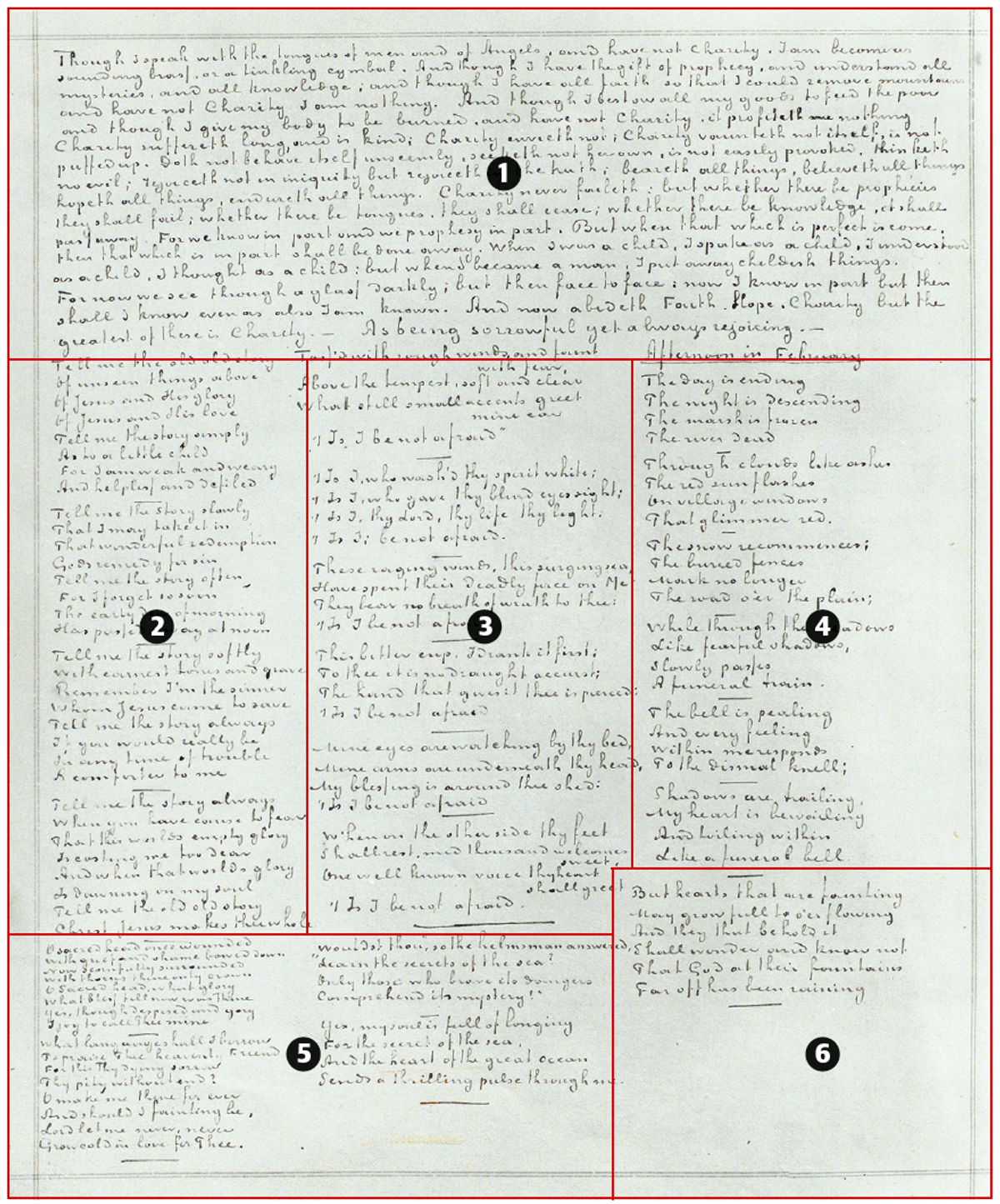

A stanza from Longfellow

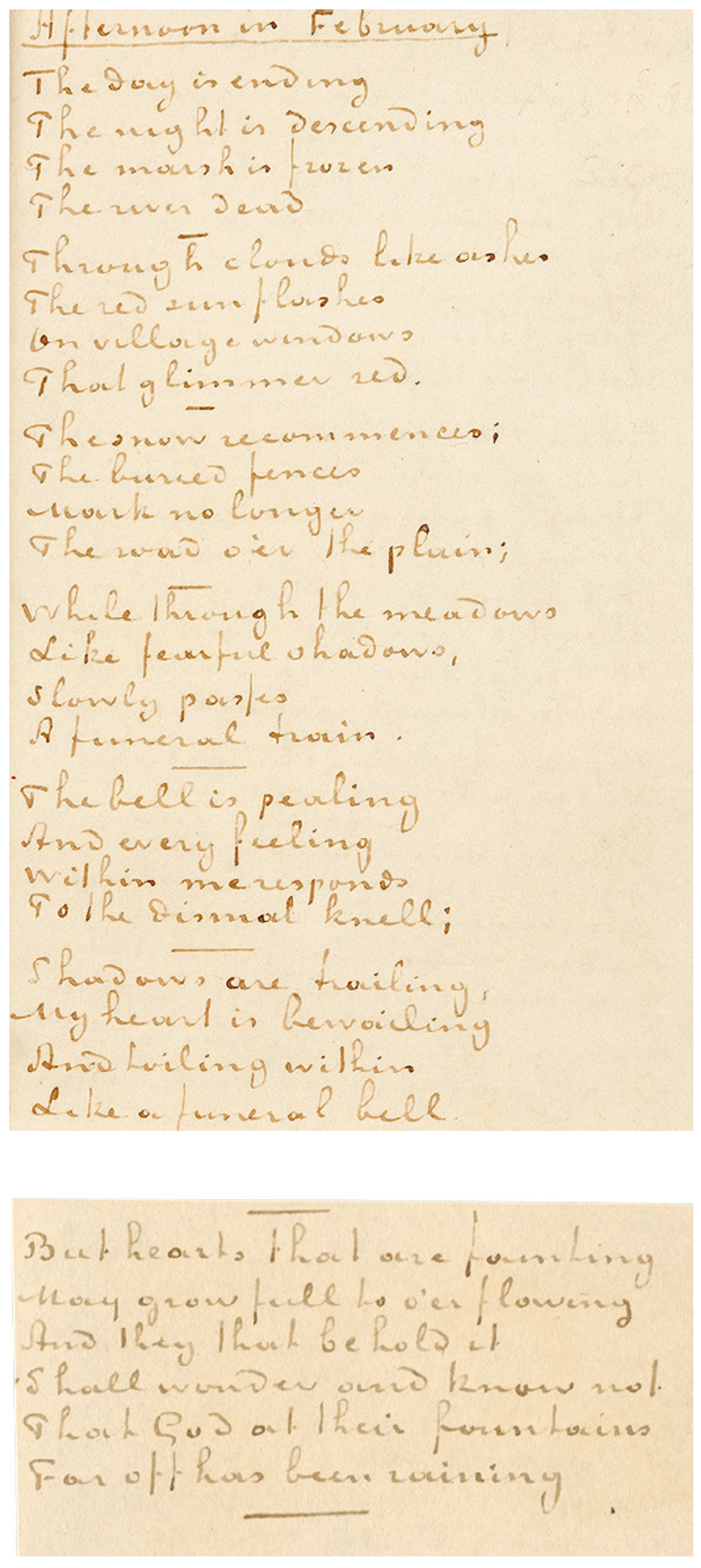

The brutal way the manuscript has been dismembered can be vividly seen from the second of the six pages of text. Two fragments from the second page ended up at the Getty and two others have passed through the trade, although their present locations are uncertain. No traces have been found of two fragments (1 and 5, above) from the top and bottom of this page. The larger Getty piece (3) has the English hymn Tossed with Rough Winds, and Faint with Fear. Their second fragment (6), just an inch high, is the last stanza from Longfellow’s poem Afternoon in February. The first five stanzas of Afternoon in February are on a separate fragment (4). This emerged at Christie’s, London in 2008, selling for £7,500. It was then acquired by the German dealer Thomas Kotte, who offered it for €27,500. This fragment was later bought by the Paris company Aristophil, which was declared bankrupt in 2015, and its collection was later consigned to the Aguttes auction house. It put up Afternoon in February for sale in 2018, with an estimate of €20,000-€25,000, although it failed to find a buyer.

The artist’s transcribed Longfellow poem that was cut in two Photo: © courtesy of Aguttes, Neuilly-sur-Seine and Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Another fragment (2) is the hymn Tell Me the Old, Old Story. In 1991 Diana Rendell, the former wife of Kenneth Rendell, advertised it for $12,000. By 2004 it was with the Californian dealer and auction house Profiles in History, on sale for $45,000. In 2011 it was offered by Fraser’s Autographs, London for £50,000.

The whole album had sold for £550 in 1980. The Aguttes fragment was estimated to be worth around £20,000 two years ago. Since this four-inch fragment represents less than 3% of the total text, on this basis, all the Van Gogh pages might now be worth around £750,000. But the tragedy is that the words which Van Gogh lovingly copied out for his landlady have now been scattered.

• For the full story of Van Gogh and his beloved pipe, see Martin Bailey’s blog Adventures with Van Gogh at theartnewspaper.com